Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, a new feature in which books journalists from around the US share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic from a different part of the country, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to literary critic and author Mark Athitakis.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

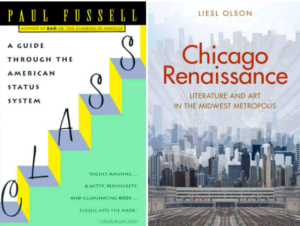

Mark Athitakis: Is Paul Fussell’s 1983 book Class a classic? It ought to be. I vividly remember being knocked backward by it when I discovered it in high school—it’s a funny and erudite study of the American class system, something that was a complete mystery to me as a suburban kid and a child of immigrants. It wasn’t much fun to learn that, by Fussell’s reckoning, I was high-prole at best. But it attuned me to ideas of class that I still pay close attention to as a reader. I would’ve loved to have reviewed it at the time to thank Fussell for all he taught me, if that isn’t too weirdly time-warping.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

MA: I love Liesl Olson’s Chicago Renaissance, which makes a persuasive case for the city as a Modernist center. It’s filled with well-turned studies of Gwendolyn Brooks, Gertrude Stein, Richard Wright, Ernest Hemingway, the circle around Poetry magazine, and daily newspaper critics. I’m invested in the idea that the Midwest is nowhere near as jus’-folks-y as stereotypes suggest, and Olson does a great job of laying out why that was true a century ago.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

MA: Two contradictory myths persist. One is that we’re professional killjoys who detest genre fiction, humor, or what have you. The other is that we are professional milquetoasts, praising junk to the skies as the willing tools of the publishing industry. We’re either flinging hatchets or doling out cupcakes. What connects both attitudes is the presumption of dishonest motives—that we’re all scheming to get ahead, somehow, by sharpening or softening our opinions. If more people saw the average book-review check, they’d stop thinking that—it’d take a long time to become even a healthy thousandaire as a craven hatchet-jobber. Critics on the whole love books and are often disappointed by them, but mostly we’re just people moved to explore what makes a book (and books in general) interesting.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

MA: I don’t think it’s much changed what criticism looks like—there are still quick-hit squibs, midsize reviews, and longform essays. But one thing we’ve lost amid this mass disruption in journalism is a sense of consistency—that there were critics who were at stable perches and writing at a weekly or monthly clip, and that you knew where to find them and you got to know them. You built up a familiarity with their tastes, their likes and dislikes. Most critics like myself now have to patch together gigs at various places, and social media helps solve that get-to-know you problem—a critic with a good Twitter feed isn’t just pointing to their work but sharing their sensibility on a regular basis. Overall, it’s made the business of criticism—and writing in general—less mysterious.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

MA: I served on the National Book Critics Circle board when we gave the Balakian Prize for reviewing to Parul Sehgal; that she’s since risen to a staff-critic position at New York Times is a happy event and not even a little bit surprising. Jane Smiley—who as a novelist deserves to be put ahead of DeLillo and Roth in U.S. Nobelist sweepstakes—writes superb criticism as well. About a decade ago we all got spoiled when Harper’s gave Wyatt Mason a blog called Sentences that was a master class in close reading, stylish writing, and the practice of criticism. The blog is no more, but I still seek out Mason’s work wherever it appears; he’s the only critic I have a Google Alert for.

*

Mark Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Humanities, Virginia Quarterly Review, and many other publications. He is the author of The New Midwest (Belt Publishing, 2017), a study of contemporary fiction from the region.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.