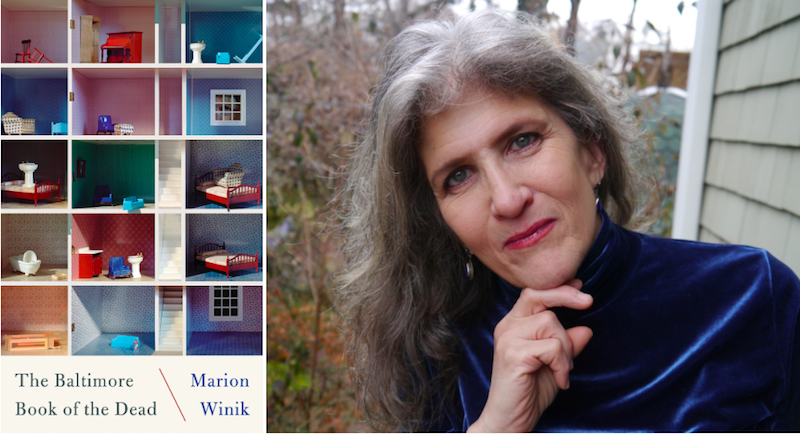

Marion Winik’s The Baltimore Book of the Dead is published this month. She shares five books of the dead with Jane Ciabattari.

Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters

A collection of free-verse autobiographical epitaphs in the voices of 212 residents of a small town called Spoon River, many of the speakers revealing secrets and relationships which never came to light during their lives. Some of the characters were based on real people. As soon as I thought of the idea for the Glen Rock Book of the Dead, the first of my “books of the dead,” I realized I would be writing a modern, nonfictional update of Spoon River. I had been in a stage production of Spoon River in middle school, and reread it with renewed appreciation.

Jane Ciabattari: I remember seeing a staged middle school production in the small Kansas town where I grew up. It seemed a natural narrative, giving glimpses of a small town with a few hundred folks. When I revisited Spoon River in graduate school, I was an urban dweller, and had to break it down in terms of a neighborhood. And I had a much better appreciation of Masters’s subversive side, which showed up in epitaphs like that for Cassius Hueffer:

| They have chiseled on my stone the words | |

| “His life was gentle, and the elements so mixed in him | |

| That nature might stand up and say to all the world, | |

| This was a man.” | |

| Those who knew me smile | 5 |

| As they read this empty rhetoric. | |

| My epitaph should have been: | |

| “Life was not gentle to him, | |

| And the elements so mixed in him | |

| That he made warfare on life, | 10 |

| In the which he was slain.” | |

| While I lived I could not cope with slanderous tongues, | |

| Now that I am dead I must submit to an epitaph | |

| Graven by a fool! | |

Do you have favorites amongst the 212?

Marion Winik: I just went through it trying to pick and found I really can’t. The ones I played in fifth grade I still know by heart, though I barely understood them at the time. A lot of very grown-up things happened in Spoon River. I was Julia Miller, who killed herself with an overdose of morphine, and Lydia Puckett, whose boyfriend joined the army after she cheated on him, and Pauline Barrett, who had a hysterectomy. More than any one of them, what I love is the way they fit together, all the melodramas that unfold, the adulterers and drunks and unhappy marriages—that little town was a real Peyton Place.

Our Town by Thornton Wilder

This classic play gives us a rare and almost shocking opportunity to view everyday life as we might see it after it has been snatched away from us forever. When, in the third act, Emily revisits her twelfth birthday party from her new point of view as one of the dead—as an aside, the cemetery scene now feels connected to Lincoln in the Bardo—she is heartbroken to realize how little the living value what they have. The way death creates a context for life is exactly what my book is about, though I’m a little more optimistic about it than Wilder.

JC: Another classic. And a melancholy one. As the Stage Manager points out, a thousand years from now this play shows Grover’s Corners “the way we were: in our growing up and in our marrying and in our living and in our dying.” Your tone, as you say, is lighter, despite the fact you’re in parallel with Emily’s lament, “’It goes so fast.” What makes you able to do that?

MW: When I say I’m more optimistic than Wilder, I mean I do believe that many people appreciate life while they are living it. (Maybe because they’ve seen Our Town and it reminded them.) As for lightness—there’s comic relief in my books of the dead, but there’s also quite a bit of heartbreak. There’s nothing funny about a young girl dying in a car accident. The goldfish I accidentally murdered is another story. And yet there’s one about a dog that is a real tearjerker. Hopefully readers experience a whole spectrum of emotions when they read the book, not just for the people I write about but also for their own losses and memories.

A Grief Observed by C.S. Lewis

A brief journal kept by the author after the death of his wife, Joy Davidman, candidly documenting the intensity of his pain and bewilderment, engaging with issues of religious faith but not in a way that rules the book out for nonbelievers.

JC: Lewis seems, at first, inconsolable, which seems a natural response to such an intimate loss. “No one ever told me that grief felt so much like fear,” he writes, as the first step in outlining the raw emotions he experienced.

MW: Like Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking, Lewis observes his process closely and describes it incredibly articulately. Reading grief memoirs can help a bereaved person feel less alone. It’s as if the book creates a little grief support group of two, author and reader.

When Bad Things Happen to Good People by Rabbi Harold Kushner

I first came to write about death when my first baby was stillborn in 1987. I read this book, one of the original bestselling self-help books back when this genre first hit the ground. Its central point, that the only power we have in the face of tragic losses is to decide what kind of person we become as a result of them, became a guiding light for me. Recording and remembering and preserving the stories of people who are gone, trying to bringing light and humor and grace to that process of remembering is what my books of the dead are all about.

JC: Rabbi Kushner writes from such a personal perspective—about the loss of his son, who was diagnosed at three with a condition that meant he wouldn’t live past his teens—that he brings incredible depth to chapters like “Why do the righteous suffer?” And “Sometimes there is no reason.” I like what you say about deciding what kind of person you become as a result of tragic losses being a “guiding light” for you. Are there other aspects of Rabbi Kushner’s book that have stayed with you as well?

MW: Honestly I don’t remember a single other thing about it, but this one idea shaped my experience after losing the baby pretty powerfully. There’s a piece in The Baltimore Book of The Dead about my cousin’s daughter, born several months premature, called “The Very Tiny Baby.” In it, I comment that different women have quite different responses to pregnancy loss. Some hold it close forever, some let it go. I needed to let it go and somehow Kushner’s book helped me find a way to do that.

How We Die by Sherwin B. Nuland

This National Book Award winner, along with Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’s On Death and Dying, are the required texts for Death 101. With its clinical descriptions of how life ends, Nuland’s book strips away the myths and magical thinking and emotionality surrounding death. Goodbye, golden tunnel of light. And every bereaved person needs to read all about the five stages of grief, if only to rebel against, to claim they only went through three, or discovered a sixth and seventh, or just to conclude that the whole thing is a crock.

JC: Death, writes, Nuland, is “simply an event in the sequence of nature’s ongoing rhythms”—this after giving a vivid description unsuccessfully as a young doctor to save the life of a man who’s just had a heart attack. Kubler-Ross gives structure to the survivors. Do you think our culture has become better at facing the reality of death?

MW: I don’t know if there’s one answer for the whole culture. So many different factors and traditions play into it, and it has a lot to do with individual personality, too. One approach I really love is the Mexican tradition of Day of the Dead, which combines mourning and celebration so beautifully. When I found out about Day of the Dead—this was when I lived in Texas, in the 80s—I was crazy about it. It’s a whole set of positive rituals for remembering the dead, including putting together personal ofrendas (altars) and decorating them with photographs and marigolds and candles; eating skull-shaped cookies, candies, and pan de muertos; visiting the cemetery with a bottle of tequila. The newspapers publish calaveras, short comic poems eulogizing the living. In Austin, there was a fantastic lowrider parade. Writing about people the way I do in the books is related to all that—mourning and celebration at once.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.