Once there was a tree, and she loved a little boy.

*

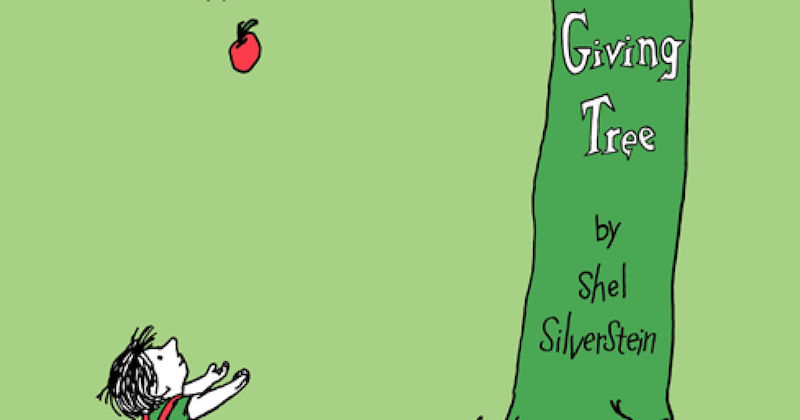

“A few weeks ago, rummaging around the Strand, I came across a fiftieth-anniversary edition of Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree. It had the fern-green cover familiar from childhood, the same oversized dimensions, the same appealing sketch on its front—a squiggly drawing of a tall tree, its top spilling off the page, and a little boy, looking up at it. But instead of experiencing a pleasant rush of nostalgia, I was dismayed. A strange thing happens when we encounter a book we used to love and suddenly find it charmless; the feeling is one of puzzled dissociation. Was it really me who once cherished this book?

…

“A little Googling corroborated my own distaste. The Giving Tree ranks high on both ‘favorite’ and ‘least favorite’ lists of children’s books, and is the subject of many online invectives. One blog post, ‘Why I Hate The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein,’ argues that the book encourages selfishness, narcissism, and codependency. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, environmental activists rue the boy’s pillaging of the tree and, by extension, the environment. William Cole, who turned down the manuscript when he was an editor at Simon & Schuster (Silverstein took it to Harper & Row), was troubled by its portrayal of parenthood: ‘My interpretation is that that was one dum-dum of a tree, giving everything and expecting nothing in return.’ More recently, the children’s-book author Laurel Snyder said, ‘When you give a new mother ten copies of The Giving Tree, it does send a message to the mother that we are supposed to be this person.’

Still, it’s difficult to know whether Silverstein, who died of a heart attack in 1999, after keeping out of the public eye for more than two decades, meant for us to read the book so conclusively. His biography and body of work suggest a subtler, and, in the end, perhaps an even more troubling, way of looking at it.

“As becomes clear from reading Rogak’s biography, Silverstein never intended to write or draw for children. He was often impatient around kids and, Rogak claims, ‘made no secret of the contempt he felt’ for most children’s books. ‘Hell, a kid’s already scared of being small and insignificant,’ he once said. ‘So what does E. B. White give them? A mouse who’s afraid of being flushed down the toilet or rolled up in a window shade and a spider who’s getting ready to die.’ But writing kids’ books was the complete opposite of the work he was doing for Playboy and, maybe for that reason, and with the prodding of a savvy editor, he decided to try his hand at it.

The result was a classic Silversteinian burst of productivity: in 1964 alone, he published three children’s books and one book for adults. Among them was The Giving Tree, whose breakaway success caught by surprise not only his publishers, who had printed a modest run of seven thousand copies, but also Silverstein himself, who claimed it had no message. Sales of The Giving Tree doubled every year in the decade following its publication; they have since topped five million copies worldwide. But Silverstein was continually asked to defend the book, and this seems to have sapped his energy. ‘It’s just a relationship between two people; one gives and the other takes,’ he would often repeat.

“If madness is what he was after, then the The Giving Tree might be read as another expression of it, perhaps a cousin to a song Silverstein wrote, called Fuck ’Em, in which he cheerfully exclaims, ‘Hey, a woman come around and handed me a line?/ About a lot of little orphan kids sufferin’ and dyin’?/ Shit, I give her a quarter, cause one of ’em might be mine.’ Rogak, his biographer, has her own explanation for The Giving Tree’s portrayal of self-abnegation—one that echoes his beatnik years: ‘Given his disgust with the me-first attitude among the folksingers and other artists in the Village who were creating art as a form of self-analysis, it almost sounds like he wrote it as an experiment, a reaction to their own mushiness.’

The dismay I felt on rereading the book soon gave way to something else. Finding that a childhood favorite wasn’t at all what I remembered carried with it a peculiar thrill, a kind of scientific proof that I’d grown up and changed. And, if I’ve changed, perhaps The Giving Tree has, too. What, for example, does Silverstein mean with his injection of the flat, repetitive ‘happy’? He wasn’t one for happiness. In fact, the book’s illustrations seem to undermine this very conceit. ‘And the tree was happy,’ we are told, but all we see is a sorry stump and a hunched old man staring forlornly into the distance. Is she happy? We have to ask. Is he? Or maybe the book isn’t about love or happiness at all, but a lament about the passing of time, an unsentimental view of physical decay, a withering away. Maybe it’s enough to take Silverstein’s own reading of it. ‘It’s about a boy and a tree,’ he once said. ‘It has a pretty sad ending.’”

–Ruth Margalit, The New Yorker, November 5, 2014

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.