Better never means better for everyone… It always means worse, for some.

“We must think of ourselves as tourists, travelers in time. These streets are familiar, yet it would appear we have entered the Dark Ages. We are in a well-tended suburb in New England. Pleasant old houses, manicured lawns. A college town, perhaps Cambridge, although it is evident that the university has been closed permanently. Hooded bodies hang from hooks against an old brick wall, black vans with eyes ominously painted on them patrol the streets, uniformed men are stationed at checkpoints. On these streets there is an absence of children and old people. Everyone is also white.

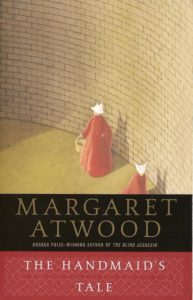

Women are dressed oddly in floor-length costumes that appear to delineate caste—wives of commanders wear blue with matching veils, the dresses of ‘econowives’ are striped. And then there are the young women in red habits, who look so medieval with their white-winged headdresses—the handmaids. They walk demurely in pairs with their baskets, careful to avoid eye contact with strangers.

…

“Life as we know it in the U.S.A. no longer exists. We have entered the Republic of Gilead.

…

“In The Handmaid’s Tale, her fifth and most powerful novel, she looks into the clouded glass of the future and, fully attuned to some of the negative signals in the present, envisions startling but by no means illogical consequences. In opening her imagination to what we might find some years down the road, Atwood joins the company of Doris Lessing, J.G. Ballard and Anthony Burgess, literary writers of future shock fiction—a genre whose pioneers include H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, and George Orwell.

…

“…the novel of the disastrous future offers the writer of fiction rejuvenated possibilities. Characters are placedmis, calling upon all their resources of courage and ingenuity in order to survive. Rebels defy the rules of society, risking everything to retain their humanity. If the world Atwood depicts is chilling, if ‘God is losing,’ the only hope for optimism is a vision that includes the inevitability of human struggle against the prevailing order.

…

“Just as the world of Orwell’s 1984 gripped our imaginations, so will the world of Atwood’s handmaid. She has succeeded in finding a voice for her heroine that is direct, artless, utterly convincing. It is the voice of a woman we might know, of someone very close to us.

…

“The Handmaid’s Tale is a novel that brilliantly illuminates some of the darker interconnections of politics and sex, and it will no doubt be labeled a ‘feminist 1984.’ Yet it is Atwood’s achievement to have produced a political novel that avoids the pitfall of doctrinaire writing.

…

“Gilead threatens those who break its rules with extinction. Yet for Offred, the price of obedience is even higher—the death of the senses, the death of the spirit … Overwhelming loneliness and boredom afflict her even more than oppression. ‘Nobody dies from lack of sex,’ she discovers. ‘It’s a lack of love we die from. There’s nobody here I can love, all the people I could love are dead or elsewhere. Who knows where they are or what their names are now? They might as well as be nowhere, as I am for them. I too am a missing person.’

Offred’s plight is always human as well as ideological, and so is her inevitable assertion of her needs. Her tale, in Atwood’s masterful hands, is extraordinarily satisfying, disturbing and compelling.”

–Joyce Johnson, The Washington Post, February 2, 1986