Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

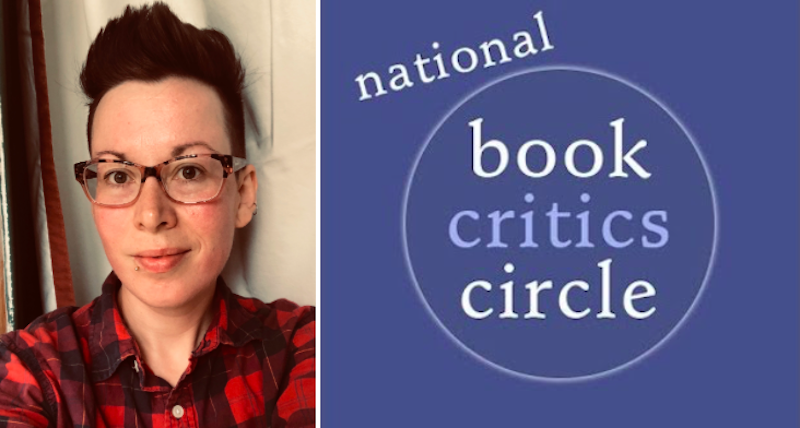

This week we spoke to Virginia-based poet, writer, and critic, Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers:This is a terrible question! Suddenly, I have a lifetime of reading jockeying for position. One of the things that makes this question so hard is the term “classic.” For me, that implies literary cannon, and so much of what’s moved me and shaped me as a reader and writer isn’t included in that cannon. I’m deeply aware of how the classics I’ve loved are flawed. Books are cultural artifacts, and I’m resistant to the idea of a book that’s timeless. There’s also the fact that I’m not timeless either, so, even though a book’s content is stable, the way I understand it shifts as my understanding of myself and the world grows.

Caveats caveated, if I had a time machine, I’d like to review Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Not only would I like to discover whether or not those missing tales really were unwritten at his time of death, I’d love to be part of the critical conversation and general reception to the tales when they were first printed. Representation is still an issue in books, and Chaucer’s characters show a range that’s unprecedented in English literature before him. Not only are they from a variety of social classes and genders, those characters are wild. Everything about the tales centers human interactions. It crackles with social energy, and I’d love to have been there for such a radical work’s debut.

Even sans time machine, I’d love to review it. It’s so compelling! There’s a wry, tongue-in-cheek energy that floats the verse, and Chaucer’s voice is so alive and present. It’s also joke dense, and so many of the jokes translate even six hundred years later. Whenever I pick it up, I just want to keep reading, and I inevitably feel like I’ve been to a comedy show. The structure, delivery, and payoff I get as a reader feels the same. Chaucer’s there to make sure you have a good time (at the expense of the status quo), and any author that’s still making me laugh centuries after he’s in the ground is someone I’d like to devote some serious critical energy to.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

LMR: Technically, this book is from 2017, but I always think those December publication dates are hard on their titles. Not only are those books coming out when most of us are engaged in year-end wrap-ups, if anything goes wrong, suddenly, a book with a publication date in one year isn’t actually attended to or available until the next. I think this circumstance has a lot to do with why Kayleb Rae Candrilli’s What Runs Over got overlooked because it certainly isn’t the writing or the content!

A heart-stopping memoir in verse, What Runs Over tells the story of the speaker’s identity development around issues of gender, class, and sexuality, and the work of discovery happens in ways I found truly unique. There’s an immediacy in the narrative’s unfolding, as if you’re part of a conversation happening right now. Past and present are interpolated to get at that sticky truth beyond truth, the deep things that memory and story can sometimes occlude rather than reveal. When the speaker casually asks what you’d think if, in the middle of the book, they changed their name to Kayleb, I couldn’t breathe. It was such a commanding revelation of their trans identity, the emotional stakes perfectly counterbalanced and heightened by the delivery.

There are lots of ways a book can move me, but it’s rare for me to have the visceral response I had to What Runs Over. It’s only 97 pages long, but I had to read it in three or four sittings. Parts of it made me physically ill, parts made me weep, parts awed me. Ever since, I’ve been trying to codify all the technical, aesthetic, social, and personal reasons this book affected me, and I haven’t come to the end of my list. Because this book still moves me—is still moving through me, really—I’ve utterly failed it as a critic. I’m failing it now. I feel inept in the face of the work, still lacking a definitive criterion for its power. No matter what I say about it, it’ll only be a gloss of all the ways What Runs Over is thinking, feeling, and constructing what it means to be embodied—in the world at large, in the closer world of self, and at the confluence of the two.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

LMR: The greatest misconception I face are two sides of the same coin. One is that book critics are elite urban intellectuals (usually New York City-based), whose full-time profession is to heap negativity and scorn on books for great financial reward. The other is that book criticism is unserious, undemanding part-time work based on enthusing about your personal reading preferences. Not surprisingly, there’s gendered elements to both these assumptions. In the first, it’s a serious, tweedy male whose opinions carry the weight of insight and deserve financial and institutional space. This hypothetical critic’s labor is intellectual work. In the latter, it’s a housewife or single woman using books as an escapist narcotic, and her opinions are conflated with feelings and should be made available to the public for free. This hypothetical critic’s labor is emotional. This dichotomy’s frustrating, not only because these gendered understandings of intellectual capital seem antique, but because critical work is as much a victim of the gig economy and the crisis of capitalism as anything else. It’s caught between celebrating publishing’s democratization and struggling to forge a path forward in the face of decentralization. Book critics don’t fit these assumptions anymore (if they ever did), yet the weight of these assumptions is still something I have to push against.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

LMR: In many ways, social media makes the conversation more expansive. I have quicker access to so many perspectives and writers and critics; I’m pointed toward more books and more ways of talking and thinking about books than ever before. At the same time, it’s easy to get overwhelmed and engage more lightly. At its worst, social media feeds into the anti-intellectualism of our current moment. Why read a professional critical review when there are “real” reviews on Amazon?

I’m not the first person to note this tension, and pointing it out isn’t the same as resolving it. We’re all being told the problems of late-stage capitalism are a matter of individual performance while it’s clear the forces shaping society are well beyond the scope of a lone individual’s ability to affect. I think social media, especially in the ways it’s purveyed as the place where we “come together,” plays both sides against the middle, the myth of individual merit driving the collective. I’m not sure how we’re going to become individuals pulling together in a system that, fundamentally, doesn’t seem designed for it, but we seem to be really far on one side of the pendulum swing. There are still unaddressed issues on the table, there’s still work to be done, and our critical capacities are needed in this area of our work as much as in our reviewing.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

LMR: I don’t think there’s one critic I go to for everything. I love reading Helen Vendler because she’s a genius. Her critical voice is finely-honed, she takes a definitive stance, and her knowledge and experience in the field of poetry is astounding. There’s a challenge in her work; it refuses to let me read passively. Even in her reviews, I must wrestle with what I think about what she’s saying. I cannot be a spectator. I also love reading Anjali Enjenti’s work. Her astute and devoted political journalism brings a perspective to her critical work that I appreciate. She’s reading in multiple directions, always with an eye to a first-hand experience of society and politics at a grassroots level. I also love the work of Ismail Mohammad, who’s just been named reviews editor at The Believer. He combines cultural criticism and reviewing seamlessly, creating these wide, interconnected networks of meaning between books as cultural products and the culture that books produce.

*

A poet, writer, book critic, and farmer, Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers earned a B.A. in English from Penn State and an M.F.A. in Creative Writing and M.A. in Applied Linguistics from Old Dominion University. A finalist for the 2018 Janet B. McCabe Poetry Award and the 2018 Hal Prize, her creative work has been published in Gulf Stream, IthacaLit, Menacing Hedge, SWWIM Every Day, and Peculiar, among others. Named a 2018 Emerging Critic by the National Book Critics Circle, her critical work is published or forthcoming at The Los Angeles Review, Foreword Reviews, Orion, and The Millions. Find her talking about books and other passions on Twitter @murderopilcrows.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·