Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to New York-based writer and critic, Leena Soman Navani.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

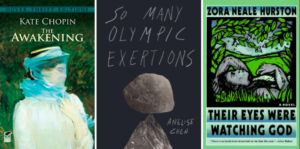

Leena Soman Navani: Any thought experiment involving traveling back in time is dicey for people of color (and women)! I understand that that isn’t the type of answer we’re interested in here, but I can’t help myself—even our most benign questions often make assumptions about power, privilege, and access, among other things. Outlets are just barely interested in what I might have to say about contemporary books, let alone the accepted classics. When I think of some of these books, I don’t know where or how I could fit into the larger society that received them. That said, Middlemarch, The Awakening, Their Eyes Were Watching God, and Beloved are some favorites.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

LSN: I’d like to shout out Anelise Chen and Kaya Press for So Many Olympic Exertions. It is a novel in fragments, and just so wonderful. I admire how the story is distilled and braided with wit and depth. Early on in the narrative, Chen writes, “Everything is hopeless, and we just have to keep going. Not that it helps, but we just have to keep going,” which is how I often feel these days.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

LSN: It may seem obvious, but we love writers, writing, and books! By definition, we are saying, “this is a piece of art worthy of our collective examination.” Not all, but many of us know what it takes to put art into the universe, not only because we are writers ourselves, but also because critics are criticized for their good and bad takes, the rigor of our analyses. Criticism is itself an artform that isn’t just about evaluation, but engagement. I think that’s easy to forget or sideline. But it’s crucial. Even when I’m criticizing someone’s work, it’s coming from a respect for the endeavor the author has chosen to pursue. Both parties, the author and critic, are searching for honesty in good faith in their own way.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

LSN: I’m early in my career as a book critic, so I don’t know that I can offer a true reflection here, but I will say that many incredible books by Asian American women are getting a lot of attention, finally, and I don’t know that it’s because of social media, but I also don’t know if that happens in a world without social media. Actually we know it doesn’t because it didn’t, even in an era when one of the most powerful critics, arguably, was an Asian American woman. Access is still an issue, among others. So while social media can and does do quite a lot to harm us as artists and professionals, especially in a society aspiring to be a democracy, its democratizing force is vital to some of us who are still at the margins. There are so many really smart, critical voices, that we should be listening to, and who simply don’t have access to gatekeepers, gatekeeping positions, or book contracts, yet, and so they’re writing threads on Twitter or posts on Medium. And through that sharing of knowledge, experience, resources, and analysis, there’s robust community.

For example, there do not appear to be any black women featured in this series. We can begin to try to remedy that within minutes today via social media. For now, social media has many dangers, but is also a very useful tool against certain systemic imbalances.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

LSN: There are so many. Parul Seghal, Hilton Als, and Roxane Gay, of course. I think often of the breadth of Julian Lucas’ review of Counternarrative by the author John Keene, who’s now a MacArthur Fellow. Sophie Gilbert recently wrote an interesting piece about feminist dystopia. And Jia Tolentino’s work is incredible.

I also find inspiration from critics of other art forms, especially film, TV, and food. Of course books are my focus, but I find that reading more widely helps me think more deeply about narrative, and what’s being attempted, accomplished, and subverted by a writer. Losing Bourdain and Gold this year has me thinking about creativity, criticism, and culture. Food is a portal to so much more, obviously, and perhaps nothing can compare to its centrality in our lives, but there’s no reason that books or stories, and our writing/commentary about them, can’t or shouldn’t also lead to more connections across culture that further enrich literary community and literature, and so on. For instance, how might the dialogue around cultural appropriation be advanced, if we put book, food, and music creators and critics in a room or on the page together in a different way? Maybe it wouldn’t, but we might learn from the cross-pollination or develop more interested ideas within certain contexts by moving among different contexts. Lit Hub had a great interview a while back, How is Reviewing a Restaurant Like Reviewing a Book, and more recently, Kaveh Akbar and Danez Smith had a conversation for Granta about food and writing and community that was so illuminating, and I just think we could be doing more of it, and more inclusively.

*

Leena Soman Navani is a 2018 National Book Critics Circle Emerging Critic. Her work has been featured with Ploughshares, Kenyon Review, Harvard Review, and Cleaver Magazine. She is a graduate of Bennington Writing Seminars and Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. You can find her on Twitter @lsoman

*

· Previous entries in this series ·