Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, a new feature in which books journalists from around the US share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recents gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic from a different part of the country, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to Kerri Arsenault of the National Book Critics Circle

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

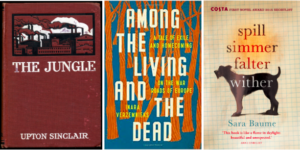

Kerri Arsenault: The Jungle by Upton Sinclair: an indictment of the meat packing industry as told through Lithuanian immigrants living in Chicago who worked in the meat packing facilities. That was the first book to make me mad, that made me want to do something, that made me want to read and write about things that matter. I read it for the first time as a senior in high school when Reagan became president and a year later, my father, a millworker and union man, went on strike. The book stuck with me, not only because it was so visceral, but because it made a difference, which is what I think books can and should do. Plus, those sentences! That scene about the sausage making! The character descriptions! Can I do a review of it now?

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

KA: Well, I’m not sure if it was heralded or not, but I’d say Inara Verzemnieks’s Among the Living and the Dead. Her book, as I wrote in the Brooklyn Rail, shows how the trauma of exile, can lead to a loss of family, culture, memory, an impoverishment that is intergenerational and shattering not only to those who experience it firsthand, but to those left behind. I also loved anything Sara Baume writes, especially her first novel published last year, Spill Simmer Falter Wither, about a man and his dog, two misfits trying to understand the world and each other.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

KA: That reading the book, and then commenting on said book, is the main job of a critic. I feel responsible for having a sound understanding of what’s happening in publishing, politics, culture, technology, the weather, cat videos, sports, and the human race alongside all societal and environmental landscapes in order to write a reflective, not just a reactive review. It’s a massive, sometimes paralyzing responsibility. Oh, and that we read fast. I have a hard time keeping up with the avalanche of books that arrive in my mailbox every day.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

KA: There are less and less places for professional book critics to publish thoughtful, considered, reviews. While certainly anyone can post an acute opinion about a book, that’s not all that criticism entails. You’d think that in the age of social media and the Internet we’d have more outlets, more venues to publish reviews online, but it’s simply not true. Sure, we can spread the word a little faster, but first we have to have a place to put those words. And why are reviews so short? You can scroll forever for the Internet at no additional cost!

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

KA: My pal, and Kirkus feature writer, Megan Labrise is a fast, furious, and smart reader and can explain the nugget of any book in three sentences or less. She’s very efficient. Also, I find Carlos Lozada, a nonfiction book critic at the Washington Post, hilarious, careful, clever, well-read, and did I mention funny? Plus, he’s a super nice guy. Last year after the election he wrote a piece, “I just binge-read eight books by Donald Trump. Here’s what I learned.” No critic likes to read a bad book, never mind eight, so what Lozada did was downright heroic. He took a hit for the rest of us.

*

Kerri Arsenault serves on the National Book Critics Circle Board, as Book Editor for Jewels of the North Atlantic and Arctic, and writes a column for Lithub. She is writing a book about Maine and how the disenfranchised are more susceptible to environmental injustices.

**

Previous entires in this series:

The New Republic literary editor Laura Marsh

Heller McAlpin, contributor to Barnes & Noble Review, Washington Post, NPR, LA Times, and others

National Book Critics Circle President Kate Tuttle

Sam Sacks of The Wall Street Journal

Laurie Hertzel of The Minneapolis Star Tribune

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.