Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

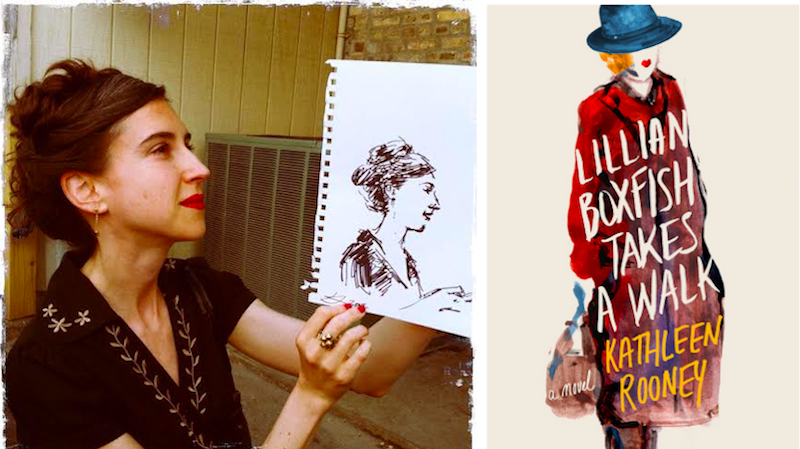

This week we spoke to writer, critic, poet, and founder of Rose Metal Press, Kathleen Rooney.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

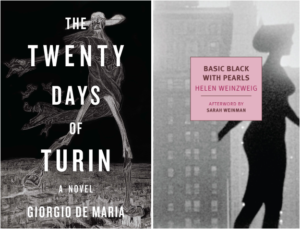

Kathleen Rooney: Basic Black with Pearls is an if not unsung then at least an under-sung novel by the Canadian writer Helen Weinzweig (1915-2010) that was originally published 1980. Sarah Weinman calls it an “interior feminist espionage novel.” The plot could be pretty easy to spoil, so I won’t say much about the story itself, but the protagonist, Shirley, is a frustrated, observant, intensely intelligent and sadly funny flâneuse.

Luckily, it’s being reissued by New York Review of Books Classics in April of 2018 and I get to review it this time around for the Chicago Tribune, so stay tuned.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

KR: Lately, I’ve been telling everyone I can to read The Twenty Days of Turin by Giorgio De Maria, a cult classic horror novel published in Italy in 1977 and released in English in the States last year. Googling around a little bit, I see that it was one of NPR’s Best Books of 2017, so I’m not sure “unheralded” is the right word, but the book is so outstanding that it could hardly be heralded enough. It’s one of the creepiest, most chilling books I’ve ever read, giving me nightmares pretty much every night I read it, but I mean all those things as compliments.

And it’s not sci-fi, but it pretty clairvoyantly predicts the internet in the form of an entity known as “The Library,” complete with high-flown claims for the invention’s benefits and spookily accurate descriptions of its sinister shortcomings, like in this scene when the amateur investigator narrator is talking to the Mayor of Turin:

“But isn’t it possible that the Library did reach one of its goals? To bring people together?”

“Oh, it reached goals! Quite a lot of goals!” he said with a dash of sarcasm. “But certainly not the goals you’re talking about! Even those infamous contributions, those dialogues across the ether that were later purged by the Library, helped break that cycle of loneliness in which our citizens were confined. Or rather they helped to furnish the illusion of a relationship with the outside world: a dismal cop-out nourished and centralized by a scornful power bent only on keeping people in their state of continuous isolation. The inventors of the Library knew their trade well.”

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

KR: Readers tend to perceive critics as performing the same function for art as like, Motor Trend or whatever performs for cars. The problem isn’t so much that readers don’t give critics enough credit, but rather that they don’t give themselves enough credit for their capacity to engage with the world as anything other than consumers.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

KR: The trend is not exclusive to social media, certainly, but a lot of aspects of culture lately have become caught up competition and quantification—trying to gamify and render winnable or losable activities and pursuits that are inherently qualitative and maybe ineffable (Iron Chef, The Voice, year-end best-of lists, best-of lists of really any kind, etc.). Social media isn’t entirely responsible for this development, but it certainly amplifies and probably depends on it. Critics these days need to be mindful of resisting that simplistic level of engagement—sorting books into piles, relying on superlatives—and concentrate instead on being precise.

That said, it sure is fun to share stuff and get retweeted! And I undeniably hope that people will see this Q&A on my Facebook wall or wherever and pick up Helen Weinzweig or subscribe to Cabinet.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

KR: As an ardent, years-long fan of Cabinet magazine, I enjoy pretty much all the criticism and essays they run in each of their themed quarterly issues. Of late, I’ve been especially impressed with the “Sentences” feature by Brian Dillon, a column in which he examines the style and mechanics of a single sentence of his choosing. In the current issue (whose theme, incidentally is “Nose”), he’s writing on a sentence from George Eliot’s Middlemarch: “Our moods are apt to bring with them images which succeed each other like the magic-lantern pictures of a doze; and in certain states of dull forlornness Dorothea all her life continued to see the vastness of St. Peter’s, the huge bronze canopy, the excited intention in the attitudes and garments of the prophets and evangelists in the mosaics above, and the red drapery which was being hung for Christmas spreading itself everywhere like a disease of the retina.”

The New York Times Magazine does a version of this feature now, too, and that one is okay, but because of its brevity and superficiality, it always feels sort of “lite” to me. I admire how Dillon is able to go into much greater depth and detail in his version of this activity—a beautiful and acrobatic form of close reading that works even if one is unfamiliar with the book that the sentence is from.

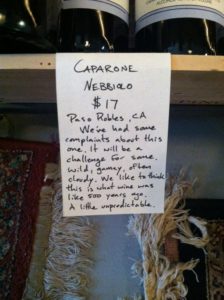

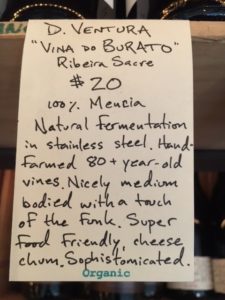

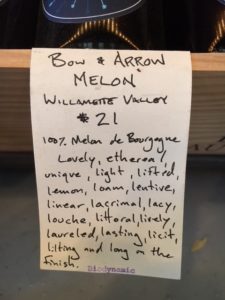

I also enjoy the shelf-talkers at Independent Spirits, a local wine shop here in the Edgewater neighborhood of Chicago, by proprietor Scott Crestodina. His write-ups are emphatic, witty, unpretentious and direct—fun to read unto themselves, even if you have no intention of ever buying or drinking the wine in question. All good criticism works that way—it’s insightful and perceptive with regard to its subject, of course, but it’s also capable of standing alone and bringing pleasure to the reader all by itself.

I mean, just look at this one about Caparone Nebbiolo:

Or this one about Vina do Burato Ribeira Sacre:

And you pretty much have to read this one about Bow & Arrow Melon out loud for the sake of all that zany alliteration:

You learn so much and you just get the sense that you’re in the presence of a critic who’s making discoveries and having a ton of fun—that’s how it should be done.

Last but not least, I highly recommend Megan Campbell and Ander Monson’s annual tournament of songs and essays, March Shredness. This year, it’s a competition of hair metal songs, but in the past they’ve done one-hit wonders (March Fadness) and melancholy tunes (March Sadness). Every year, the participating writers who represent each song do some of the most complex and engaging personal/critical writing available on the internet. Even if you’re not well-versed in the genre, the essays pull you in and make you care.

*

Kathleen Rooney is a founding editor of Rose Metal Press, a publisher of literary work in hybrid genres, and a founding member of Poems While You Wait, a team of poets and their typewriters who compose commissioned poetry on demand. She teaches English and creative writing at DePaul University and is the author of eight books of poetry, nonfiction, and fiction, including the novels O, Democracy! (Fifth Star Press, 2014) and Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk (St. Martin’s Press, 2017), and the novel in poems Robinson Alone (Gold Wake Press, 2012). With Eric Plattner, she is the coeditor of René Magritte: Selected Writings (University of Minnesota Press, 2016). Her reviews and criticism appear regularly in the Chicago Tribune and the Poetry Foundation website, as well as the New York Times Book Review. She lives in Chicago with her spouse, the writer Martin Seay.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·