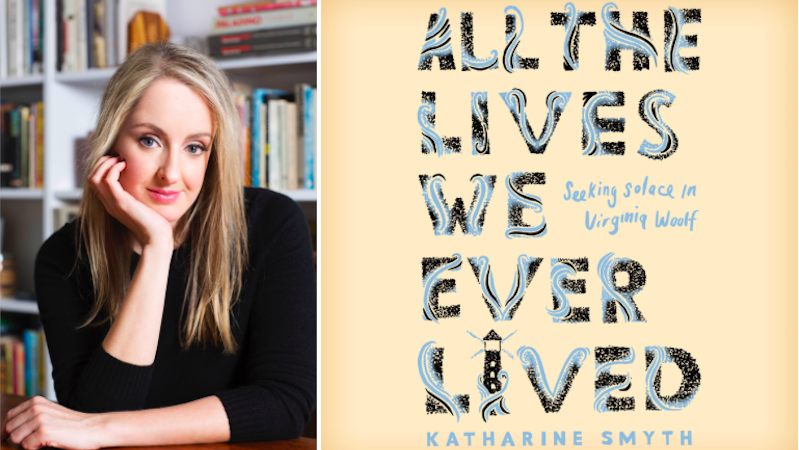

Katharine Smyth’s All the Lives We Ever Lived is published today. Smyth shares five books about fathers with Jane Ciabattari.

Independent People by Halldór Laxness

One of my all-time favorite books, Independent People is utterly immersive; all the while I was reading it, I felt as though I’d been transported, as though half of me were out at dinner in Brooklyn and the other half fighting for survival on a bleak, isolated croft in turn-of-the-century Iceland. There’s so much that I could say about this novel and its searing images—the bloody murder of a sheep against a raging storm; a dog curled up around a newborn after the mother’s death in childbirth—but most indelible of all is the fraught, moving relationship between Bjartur, a proud, stubborn farmer who has finally won his independence, and Asta Sollilja, the illegitimate daughter he raises as his own.

Jane Ciabattari: This novel by the Nobel Prize-winning Icelandic author was first published in 1946, and it’s fascinating how the landscape, the personalities, endure. Bjartur is a tough fellow; his ongoing relationship with Asta Sollilja has its rough moments. How do you feel about Laxness’s portrayal of Bjartur’s harsher judgments?

Katharine Smyth: I think it’s brilliant. Bjartur is cantankerous and cold-hearted, a repellent character in so many ways, and the cruelty and intolerance he shows his daughter—banishing her when he learns she is pregnant, for instance—should rightly turn any reader against him. But Laxness manages to weave Bjartur’s essential humanity into every page, to always conjure up his dignity and determination, so that, maddening as he is, we ultimately remain deeply sympathetic to him and his struggle—which is, of course, what it’s like to actually know someone who is cantankerous, cold-hearted, dignified, and determined. (Indeed, Independent People is a terrific model for anyone seeking to write about difficult fathers—even wicked fathers—without permanently alienating the reader.) And the roughness that characterizes Bjartur and Asta Sollilja’s relationship only makes its tender moments more poignant; the novel’s final pages, in which Bjartur reunites with his dying daughter and carries her back home, are some of the most heartbreaking I have ever read.

Light Years by James Salter

There’s a scene at the beginning of Light Years in which Viri, sitting in the bathtub after work, tells his two young daughters the story of their missing pony, Ursula: “I think she was swimming,” he says through the bathroom door. “She was trying to get the onions on the bottom.” The girls are captivated; they sit on the floor pondering river-onions and begging him to tell them more. I love this scene so much; even when Viri’s wife leaves him and his essential weakness is revealed, we remember his strength as a father and storyteller, the sense of wonder he instilled in his daughters, and that they will one day instill in him.

JC: This is one of my favorite novels ever. I reread it from time to time. I’ve seen the Hudson frozen, and the opening lines are exquisite! And yes, Viri is a storytelling dad. Are there other stories he tells his daughters that stay with you?

KS: It’s not so much the stories that stay with me, but rather the small, effortless details that suggest the sense of ease and solace and mystery that his daughters feel with him as children—their rapture as they sit together making puppets, or the way they lie along his back at the beach “like possums,” or how he is able to access their world, listening attentively as Danny explains that rabbits enjoy breakfast and can’t brush their teeth for want of a sink. There’s something so familiar about the devotion he inspires in them before they grow up and begin to see him as both a father and a (fallible) man; and something familiar, too, about the ways in which the tables will eventually turn. I often think of that scene in which Viri, abandoned and alone, calls out for his ex-wife and Danny soothes him by making tea; over the course of three hundred pages, we actually see the passing of time, actually witness the full lifespan of the father-daughter relationship.

The Return by Hisham Matar

In 1990, Hisham Matar’s father, a prominent Libyan dissident who was living in exile in Egypt, was kidnapped and taken to a prison in Tripoli; six years later, he was either relocated to a secret cell, transferred to a different prison, or executed. A deeply moving portrait of exile, uncertainty, and loss, The Return explores the pain of watching one’s father embark upon a heroic yet dangerous course—“Don’t put yourselves in competition with Libya,” he tells his wife and sons when they beg him not to publicly oppose Qaddafi—and the torment of what Matar, alluding to The Odyssey, calls his father’s “unknown death and silence.”

JC: The Return was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle autobiography award in 2017. Matar manages to encompass the complex political dimensions of his father’s life with a deeply personal story. And they had long distances between them, as you did with your own father. Which passages in The Return best describe how that distance feels to the child?

KS: I think it’s the uncertainty, and the nightmarish fantasies to which such uncertainty gives rise, that I find so devastating about Matar’s story. When my own father was dying, I found it painful to imagine the topography of his mind, to try and visualize the terror and remorse he may have felt. But Matar is faced with something exponentially more difficult than my commonplace distress: not only doesn’t he know when his father died—“Was it in the sixth year of his incarceration,” he asks, “when his letters stopped? Was it in the massacre that took place that year in the same prison?”—but he doesn’t know the nature of the fear, pain, and torture that his father almost certainly endured. The result is a book full of questions and suppositions, of pipedreams and dreadful visions, all of which serve to distance Matar from his father far more than the physical space that separated them. It’s telling that Matar’s mother calls her vanished husband “the Absent-Present.”

Zeno’s Conscience by Italo Svevo

I first read Zeno’s Conscience almost exactly a year after my father’s death, which is likely why Zeno’s portrait of his own father and that man’s punishing, protracted end—the truest, most vulnerable deathbed scene I know—stays with me so strongly. Svevo’s protagonist may be solipsistic and neurotic, but he’s also fiercely unsentimental and witty, and he offers such a relatable view of that pendulum of human emotions, from indifference to shame to guilt to frustration to remorse, that our parents alone can elicit.

JC: And that final moment, as the father raises his hand to strike his son, is indelible. How did Svevo’s approach influence you as you worked on your book?

KS: Part Two of my book takes places almost entirely in the hospital, as I’m sitting by my father’s bedside, and I actually wrote a draft of those scenes many months before I first read Zeno’s Conscience. So I think of Svevo’s approach less as an influence and more as a homecoming—I can still remember my astonishment at the almost uncanny congruence between Zeno’s experience and my own, from his evocation of the timeless limbo into which death thrusts us, to his feelings of resentment toward the increasingly demanding patient, to his desire to catalogue each new stage of decay. Even our language and syntax are similar in places—a testament to the universality of the experience, perhaps. But where Svevo especially excels is in his humor; despite the pathos of the situation, and the grimness of the subject matter, there are countless lines that make me laugh out loud. And I would suggest that this, too, is universal—that death is so hard to fathom that our regular, everyday selves, the ones that like to revel in life’s absurdities, can’t help stepping in sometimes.

My Father and Myself by J. R. Ackerley

When Roger Ackerley died, he left behind a letter that exploded his son’s understanding of his father’s life and character. In this “examining and self-examining book,” J. R. Ackerley—a gay writer and editor who seemed to have little in common with his upright, business-minded father—seeks to understand his father’s double life and why he might have kept it from his son. My Father and Myself, which I can’t help seeing through the lens of my own father’s secrets, is a vivid reminder of the limits of knowledge, of how much we don’t know even about the people we know best.

JC: Family secrets may lead to the most powerful revelations, and when the information is posthumous, it leaves lingering questions. Which parts of his father’s life were most surprising to his son? And of your father’s life most surprising to you?

KS: After his father’s death, Ackerley learned not only that his father had for decades maintained a second family, but also that he may have had homosexual encounters; he describes the former revelation (which came first) as a “jolt” that gradually began to grow in impact, and compares it to having dinner with an old friend who later goes home and puts his head in the oven. Most compelling about the discoveries—which Ackerley approaches almost clinically—are the surprising similarities they suggest between the writer and his father, whom in life he had regarded “more as a useful piece of furniture than as a human being.” My own posthumous revelations, about a father I once believed I knew to his core, had a different effect—rather than bringing us closer, they forced me to confront the boundaries of intimacy, the possibility that he might have had so many more secrets of which I was unaware. As Ackerley writes, “My relationship with my father was in ruins; I had known nothing about him at all.”

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.