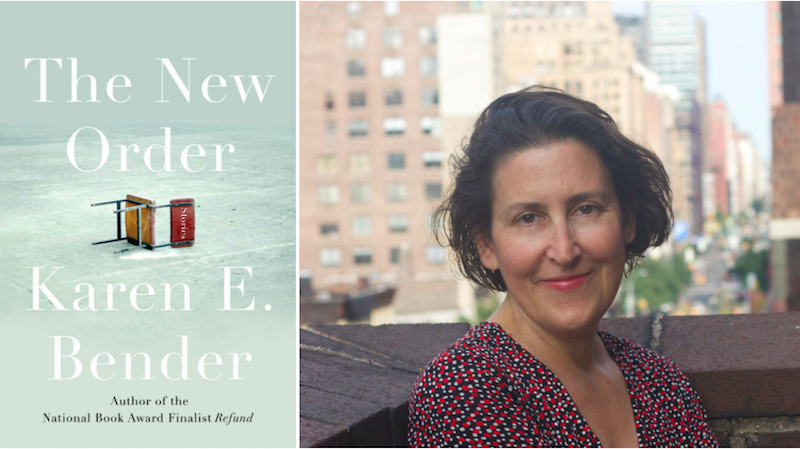

Karen E. Bender’s The New Order is published today. She shares five books in her life with Jane Ciabattari.

Goodbye, Columbus by Philip Roth (especially the story “The Conversion of the Jews”)

I still remember sitting in my twelfth grade English class and reading this story—of Hebrew school, and the contradictions and complexities therein. How did he do this? The clear-eyed way he saw hypocrisy in the school, and Ozzie’s desperate desire to understand theology and identity, the way he evoked the mother, the rabbi, Itzie, the way Roth’s characters were not simply written but lived. I was affected by this line: “If one should compare the light of day to the life of man: sunrise to birth; sunset—the dropping over the edge to death; then as Ozzie wiggled through the trapdoor of the synagogue roof, his feet kicking backward bronco-style at Rabbi Binder’s outstretched arms—at that moment the day was fifty years old.” What was this? How did anyone think of this? It was a call to a playful openness of perception, and it nourished my own ability to look at the world a new way.

Jane Ciabattari: Philip Roth opened pathways for so many writers with that first book, published in 1959 and a National Book Award winner. I think it’s as if he were born with an inner tuning fork that captured every single key on the piano. Here’s another line from “The Conversion of the Jews,” as Ozzie’s friends urge him to jump and Rabbi Binder begs him not to: “Yearningly, Ozzie wished he could rip open the sky, plunge his hands through, and pull out the sun; and on the sun, like a coin, would be stamped JUMP or DON’T JUMP.” The energy in that line is remarkable. Plus his humor throughout. How do you think Roth has influenced the American short story form?

Karen Bender: Yes, that line, too! So original and emotional. This story by Roth influenced me in its use of humor, and its clear-eyed dissection of Jewish life in America, but I actually see him as more influential in his work as a novelist. His vision is what holds across both his stories and novels—and the hilarious, honest sense of absurdity, the ability to look at first and second-generation assimilation in the United States, the yearning for freedom from family and background, yet still feeling imprisoned by it. His sense of absurdity and honesty has had an impact on not just writers but the culture in general. He is the ultimate truth teller.

Tell me a Riddle by Tillie Olsen (especially the story “I Stand Here Ironing”)

I read this during my freshman year in college, in a class on women writers. I remember reading the first line: “I stand here ironing and what you asked me moved tormented back and forth with the iron.” I was curious about motherhood, what it was like from the inside, and Olsen showed me, with the extraordinary depth and tenderness in her narrator’s voice, what it was to feel like a mother; she illuminated these feelings, and the complexity of them, in ways I had not yet read. There was a generosity and force in her sentences, in her characters, that I loved.

JC: The narrator’s regret about her nineteen-year-old daughter in some of the lines is so powerful: “She was a child of anxious, not proud love. We were poor and could not afford for her the soil of easy growth. I was a young mother, I was a distracted other….She is a child of her age, of depression, of war, of fear.” Was this the first story you ever read in which a mother reflects on raising her child, doing her best, not doing enough? Can you think of contemporary stories influenced by her work?

KB: I think it was the first story I read that explored the complexity and difficulty of motherhood in this way. I just taught this story to MFA students at Hollins and we also read stories by contemporary authors who have mentioned her as significant to their work—“Everyday Use” by Alice Walker, “Eleven” by Sandra Cisneros, “The Lesson” by Justin Torres. I also see her influence in the work of Jayne Anne Phillips and Margaret Atwood. She made clear the immense drama in the act of motherhood, and also the power of personal writing that is political. We discussed the fact that if maternity leave had been available to her, the separation from her daughter might not have been the same issue. And again, the absolute force of the narrator’s honesty.

Taking Care by Joy Williams (especially the story “The Lover”)

I read Taking Care during college and I loved the dark, unsettling honesty of the stories, the way she describes feelings that are mostly unspoken; I remember the character of “the girl” in her story “The Lover,” a story of numbness and longing. In “The Lover,” she describes her character: “The girl wants to be in love. Her face is thin with the thinness of a failed lover. It is so difficult! Love is concentration, she feels, but she can remember nothing.” Williams is a master of the absurd, and of unease, and the precise detail that brings into sharp focus what you can’t quite see.

JC: Williams describes how the girl, who is divorced, can’t sleep, and listens to a radio program called Action Line from midnight until four while her baby sleeps:

“People call the station and make comments on the world and their community and they ask questions. Music is played and a brand of beef and beans is advertised. A woman calls up and says, ‘Could you tell me why the filling in my lemon meringue pie is runny?’ These people have obscene materials in their mailboxes. They want to know where they can purchase small flags suitable for waving on Armed Forces Day. There is a man on the air who answers these questions right away. Another woman calls. She says, ‘Can you get us a report on the progress of the collection of the Betty Crocker coupons for the lung machine?’ The man can and does. He answers the woman’s question. Astonishingly, he complies with her request. The girl thinks such a talent is bleak and wonderful. She thinks this man can help her.”

Later she does call in, in a scene that feels supernatural. How does she do that?

KB: That scene you describe, toward the end of the story, happens when the girl calls the Answer Man (as he is, wonderfully, called), and asks what her hour is. He says, “Your hour came, dear,” he says. “It went back when you were sleeping. It came and saw you dreaming and it went back to where it was.” You do read this and think, what just happened? And how does Williams inject this surreal moment into this strange but essentially realist story? She sets moments of realism beside moments of utter weirdness, which I think often mirrors what life is like. She is wonderfully free in that way.

Annie John by Jamaica Kincaid (especially the story “The Circling Hand”)

I’ve heard this described as both a novel and a collection of linked stories, but I read it, in graduate school, as the latter. The stories in Annie John, which explore her childhood in Antigua, stand out to me both for their gorgeous, long sentences, and for the depth and nuance with which she viewed the ordinary concerns of growing up. She excavated the power within the experience of a being a child, which resonated with me. I especially love the story “The Circling Hand,” which details Annie’s process of separating from her mother, with whom she is very close. At one moment, Annie finds a piece of cloth and remarks how she thought it would look nice on both of them and her mother replied, “Oh, no. You are getting too old for that. It’s time you had your own clothes. You just cannot go around the rest of your life looking like a little me.” To say that I felt the earth swept away from under me would not be going too far. It wasn’t just what she said, it was the way she said it. The way Kincaid focused her eye on the mother/daughter relationship and honored the complexity of this bond was inspiring to me.

JC: She also has a marvelous way of showing an early adolescent’s moments of separating from her mother, when she starts a new school: “I told her in complete detail everything that had happened to me, leaving out, of course, Gwen and anything else that was really important.” I can’t help but think of the title story of your new collection, “The New Order,” which follows a fraught friendship between two girls in junior high, in a school where a shooting occurs, and then jumps into the future, when both girls are middle-aged. Did Kinkaid’s description of growing up give you any cues?

KB: Yes, definitely! The way she honors her deep friendship with Gwen, really her first love away from her mother, and the way small interactions with a friend at that age can make such a deep impression on you. There’s a moment in her story “Somewhere, Belgium,” in which she is talking to her best friend Gwen, and Gwen says, “I think it would be so nice if you married Rowan. Then, you see, we could be together always.” Rowan is Gwen’s brother, and Annie is horrified. She says, “I felt so alone; the last person left on earth couldn’t feel more alone than I. I looked at Gwen. Could this really be Gwen? It was Gwen. The same person I had always known. Everything was in place. But at the same time, something terrible had happened, and I couldn’t tell what it was.” She feels misunderstood—the person she feels connected to is Gwen, not Rowan—so this is an immense betrayal that she can’t share. Kincaid’s exploration of the nuances of this friendship is so moving and layered.

The Collected Stories of John Cheever (so many stories, but especially “The Country Husband,” “O City of Broken Dreams,” “The Swimmer,” “The Housebreaker of Shady Hills,” oh, just all of them.)

I have learned so much from Cheever. I read these stories when I was in graduate school, and Cheever’s sentences just made my brain light up. He packs more into a paragraph—about love, longing, loss, mortality—than most writers can fit into an entire story or novel. From him, I learned how tenderness and darkness can exist side by side, about the strangeness in the ordinary, the way every object and gesture can be a door into something miraculous. I love this line in “O City of Broken Dreams,” when Alice Evarts walks through New York City for the first time, after getting off the train from Indiana: “Alice noticed that the paving, deep in the station, had a frosty glitter, and she wondered if diamonds had been ground into the concrete.”

JC: And “The Enormous Radio,” which, like “The Swimmer,” has magical real aspects and shows us “the strangeness of the ordinary.” There are echoes of that magical real atmosphere in your story “The Cell Phones,” which begins when the rabbi tells everyone to turn off their cell phones at the beginning of Rosh Hashanah services. Do you feel a connection there?

KB: Yes, I absolutely see the connection! I love “The Enormous Radio,” which also looks at a chorus of disembodied voices, though it ends in a darker place than “The Cell Phones.” “The Enormous Radio” is another example of technology gone awry and how it both separates us and transforms us—and the power and vulnerability of the human voices that speak through it.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·