Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to Brooklyn-based writer and critic Julian Lucas.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

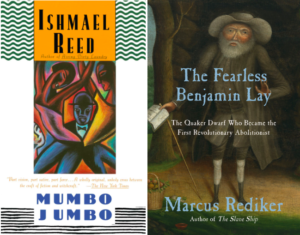

Julian Lucas: I’d review Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, the most unfairly neglected among my favorite books. Reed’s novel is a brilliant satire of the Harlem Renaissance that doubles as a Voodoo detective novel, cultural appropriation ur-text, and ersatz holy book. Carl Van Vechten—the photographer, writer, and noted “Negrophile” who Columbused the Harlem Renaissance—is portrayed as a deathless medieval Crusader scheming to save Western Civilization by neutralizing black culture, which has literally gone viral in the form of the pandemic “Jes Grew.” It’s mad, unadulterated genius—as many writers and academics have since recognized—but critics at the time couldn’t handle it. Reed was nominated for the 1972 National Book Award for Fiction, but lost to John Barth’s Chimera, which I don’t think has stood up as well. I wonder if things might have gone differently had Mumbo Jumbo received even one more open-minded review.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

JL: The Fearless Benjamin Lay by historian Marcus Rediker. It’s a short yet extremely inspiring biography of America’s first radical abolitionist, a vegetarian Quaker dwarf who lived in a cave near colonial Philadelphia. As far as I’m concerned, he was the wokest white man to ever live. Benjamin Franklin (who remarked on his terrible breath) helped Lay publish a treatise entitled All Slave-Keepers That Keep the Innocent in Bondage, Apostates, which compared his respectable slave-owning neighbors to the Beast in the Book of Revelations. Lay was gloriously uncivil. At one Sunday meeting in New Jersey, he spattered the congregation’s slaveholders with pokeberry juice before being dragged out. Today, he’d doubtless be considered a dangerous Antifa terrorist poisoning our national discourse. But he was really a tender-hearted eccentric with preternatural moral courage, an abolitionist before abolitionism. If only he’d rise from the dead and run for office in Trump country.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

JL: I don’t know if this is a misconception, but many people seem to believe that reviews are only useful before deciding to read a book. But if the review is truly insightful, reversing the order can be more enriching. I can’t tell you how many times reading a critic has sharpened my sense of a book, whether because they articulate a perception I didn’t have words for or because objecting to their judgment helps me delineate my own. More casual readers could appreciate criticism if they approached it this way—as a way of reflecting with others on a literary experience, rather than condescending instructions on what to read and think. That’s another misconception about critics, that we want people to think exactly as we do—but even if that were possible, it would only make us irrelevant.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

JL: As a mere millennial, I have no memory of book criticism before the age of social media, a phrase that makes me picture Neolithic soothsayers conjuring memes in smoke. But I think the collision of spheres it facilitates is both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it makes it easier for ideas to find their audience, and harder for reviewers to hide from the scrutiny of those beyond their publication’s usual readership. On the other hand, there is more pressure to consider every possible viewpoint when the audience is potentially everyone. Overall, I hope that much as film and television pushed fiction toward what only it can do, social media might force criticism to embrace its own singularity. Literary reviews at their best are not just “takes” but landscapes of context, revealing facets difficult to grasp when you read a book in isolation. You know how you might “know” someone, but when you visit their home, or meet their family, or hang out with their friends, something changes? That’s what a great review can do for a book.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

JL: Doreen St. Félix is always insightful and has an intuitive grasp of American media metaphysics. I admired her profile of Kara Walker in New York and her essay on appropriation, memes, and Vine for The Fader. Parul Seghal never fails to be interesting, regardless of what she thinks of a book, and her prose is exquisite. I read every review Brian Dillon writes at 4Columns. (His excellent book Essayism comes out in the US with New York Review Books in September.) Finally, Frank Guan wrote one of my favorite essays this year in The Point, where I’m web editor. It’s a review of Elif Batuman’s The Idiot that also extends her criticisms of contemporary fiction. Guan asks why so many novels refuse to engage with ideology, and the stultifying consequences of having characters with refined perceptions and complicated feelings but no politics or worldview. It’s an essay that not only identifies a lack, but suggests a way forward.

*

Julian Lucas is a writer and critic based in Brooklyn. He is an associate editor at Cabinet and web editor of The Point. His essays and reviews have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The New Republic, and the New York Times Book Review, where he is a contributing writer. He is working on a book of essays. @jcljules

*

· Previous entries in this series ·