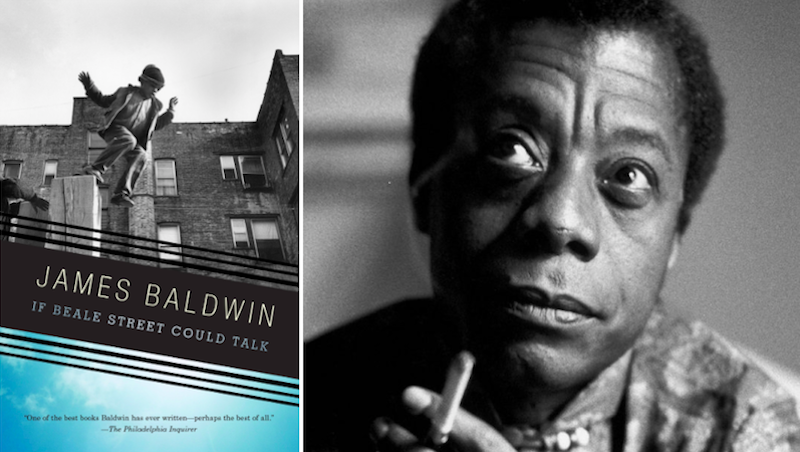

James Baldwin got a shout-out at the Oscars last night!

Yes, upon accepting her Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress—for Barry Jenkins’ adaptation of Baldwin’s 1974 novel, If Beale Street Could Talk—Regina King called the beloved author “one of the greatest artists of our time.” We heartily agree with Regina, and are grateful to her for reminding us to revisit this classic New York Times review (written by none other than Joyce Carol Oates) of Baldwin’s powerful, Harlem-set love story.

*

If Beale Street Could Talk (1974)

Neither love nor terror makes one blind: indifference makes one blind.

“James Baldwin’s career has not been an even one, and his life as a writer cannot have been, so far, very placid. He has been both praised and, in recent years, denounced for the wrong reasons. The black writer, if he is not being patronized simply for being black, is in danger of being attacked for not being black enough. Or he is forced to represent a mass of people, his unique vision assumed to be symbolic of a collective vision. In some circles he cannot lose—his work will be praised without being read, which must be the worst possible fate for a serious writer. And, of course, there are circles, perhaps those nearest home, in which he cannot ever win—for there will be people who resent the mere fact of his speaking of them, whether he intends to speak for them or not.

If Beale Street Could Talk is Baldwin’s 13th book and it might have been written, if not revised for publication, in the 1950’s. Its suffering, bewildered people, trapped in what is referred to as the ‘garbage dump’ of New York City—blacks constantly at the mercy of whites—have not even the psychological benefit of the Black Power and other radical movements to sustain them. Though their story should seem dated, it does not. And the peculiar fact of their being so politically helpless seems to have strengthened, in Baldwin’s imagination at least, the deep, powerful bonds of emotion between them. If Beale Street Could Talk is a quite moving and very traditional celebration of love. It affirms not only love between a man and a woman, but love of a type that is dealt with only rarely in contemporary fiction—that between members of a family, which may involve extremes of sacrifice.

A sparse, slender narrative, told first-person by a 19-year-old named Tish, If Beale Street Could Talk manages to be many things at the same time. It is economically, almost poetically constructed, and may certainly be read as a kind of allegory, which refuses conventional outbursts of violence, preferring to stress the provisional, tentative nature of our lives. A 22-year-old black man, a sculptor, is arrested and booked for a crime—rape of a Puerto Rican woman—which he did not commit. The only black man in a police line-up, he is ‘identified’ by the distraught, confused woman, whose testimony is partly shaped by a white policeman. Fonny, the sculptor, is innocent, yet it is up to the accused and his family to prove ‘and to pay for proving’ this simple fact.

…

“The novel progresses swiftly and suspensefully, but its dynamic movement is interior. Baldwin constantly understates the horror of his characters’ situation in order to present them as human beings whom disaster has struck, rather than as blacks who have, typically, been victimized by whites and are therefore likely subjects for a novel. The work contains many sympathetic portraits of white people, especially Fonny’s harassed white lawyer, whose position is hardly better that the blacks he defends. And, in a masterly stroke, Tish’s mother travels to Puerto Rico in an attempt to reason with the woman who has accused her prospective son-in-law of rape, only to realize, there, a poverty and helplessness more extreme that that endured by the blacks of New York City.

…

“Yet the novel is ultimately optimistic. It stresses the communal bond between members of an oppressed minority, especially between members of a family, which would probably not be experienced in happier times. As society disintegrates in a collective sense, smaller human unity will become more and more important. Those who are without them, like Fonny’s friend Daniel, will probably not survive. Certainly they will not reproduce themselves. Fonny’s real crime is ‘having his center inside him,’ but this is, ultimately, the means by which he survives. Others are less fortunate.

If Beale Street Could Talk is a moving, painful story. It is so vividly human and so obviously based upon reality, that it strikes us as timeless—an art that has not the slightest need of esthetic tricks, and even less need of fashionable apocalyptic excesses.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.