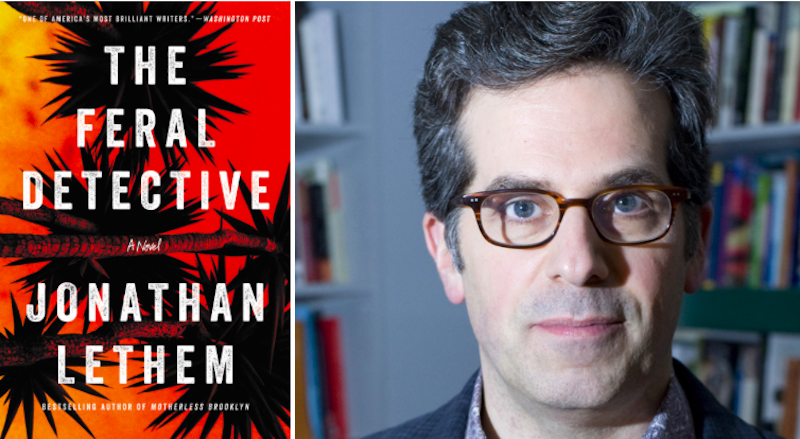

Jonathan Lethem’s The Feral Detective was just published by Ecco. He shares five books that, like his, have first-person narrators written across gender, with Jane Ciabattari.

The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch

There are many terrific examples of women-doing-men that I could have chosen, from Joyce Carol Oates’ We Were The Mulvaneys to Willa Cather’s My Antonia to A.M. Homes’ supremely-unsettling The End of Alice. Even Iris Murdoch presents other examples—one of my favorites of her novels, The Black Prince, features a Nabokovianly unreliable first person male narrator. But The Sea, The Sea is, I think, even more intricate and sublime; the narrator, a retired star stage-actor, is vastly self-deceiving and vain, yet also has a nearly Shakespearean breadth and depth of humanity—he gobbles emotions for oxygen, and everyone else around him drowns.

Jane Ciabattari: One of the challenges for Murdoch is portraying Charles Arrowby’s egocentric love for two women, one his first love, rediscovered after decades. “She’s going to leave her husband and come to me. He’s a vile man and she hates him,” he says. And there’s Lizzie, who thought they were going to be together after he left London to live by the sea. He tries to explain: “I wonder if you know what it’s like when you have to guard somebody, to guard them in your heart against all damage, and all darkness, and to sort of renew them as if you were God…” How do you think Murdoch brought authenticity to such declarations about his most intimate feelings?

Jonathan Lethem: It’s a great question. Murdoch had some kind of Shakespeareanesque capacity for standing on all sides of nearly every question her work raises. Her vision of individual experience is firmly paradoxical, with a fascination for things like “the power the meek wield over the strong”—and her casts of characters always reproduce systems of complex and unstable interdependence. No one’s as much the captain of their own fate as they imagine, and nearly everyone’s blind to the fullness of their effects on others. Arrowby’s an extreme example of her emphasis on power of romantic love to transform and destroy simultaneously. It isn’t a problem she solves, but then, how could she? What she does is make you feel it.

Mating by Norman Rush

I’d bet this is the favorite man-doing-woman first-person of nearly anyone who’s read it—in my experience, the tribe of Mating fans is a very passionate one, and many in it, like myself, feel that nothing else Rush published ever quite touched it. Which is no shame. Nor is it any shame to have learned, as we did at some point, that his remarkably real and mercurial and funny (unnamed) female-narrator is both based on his own wife and depended in many ways on her close assistance with the manuscript. We all need help.

JC: In 2006 Mating’s writer fans voted it one of the best novels of the last quarter century. Rush and his wife Elsa served as Peace Corps co-directors in Botswana, an experience that clearly shaped Mating, and the distinctive female narrative voice is, I gather, not unlike Elsa’s. Does Rush do enough to acknowledge his wife’s contributions? (She seems light-hearted about it, in a joint interview Wyatt Mason did for the New York Times Magazine.)

JL: Well, heck, who am I to judge? At least we’ve heard about the assistance she provided, which probably puts Rush ahead of the rest of us.

The Transmigration of Timothy Archer by Philip K. Dick

A major and early personal favorite, I read this first at a point in my life where the technical leap of doing a woman in first-person wasn’t even really something I’d have focused on. Dick’s narrator, Angel Archer, is arch and abiding, dealing with the absurd tragedies in the lives around her with graceful resilience and biting sarcasm, both. It’s a very unlikely acccomplishment for Dick, who mostly wasn’t otherwise at his best using first-person, nor—to put it mildly—in his portrayals of the opposite sex.

JC: I find it fascinating how Dick uses material about the late Bishop James Pike of San Francisco, who died in the desert in Israel in 1969, in shaping the character Timothy Archer, who is his narrator Angel Archer’s father-in-law. (I gather they were friends.) Angel has an idiosyncratic voice. She says things like, “A lot of people in the Bay Area date events by the release of Beatles albums” and “When one catches sight of Edgar Barefoot for the first time, one says: He fixes car transmissions.” Do you have favorite phrases, or sections?

JL: An awful lot of them! Beginning with that encounter with Edgar Barefoot (who I believe may be a thinly disguised Alan Watts) on his houseboat. And there’s the extraordinary friendship Angel forges with Bill Lundborg, a helpless schizophrenic who actually does fix car transmissions. There’s a point at which she administers a psychological test on Bill in which she asks him to interpret famous maxims, like “A new broom sweeps clean,” that’s unbelievably funny and heartbreaking. One of the things that’s striking about Dick’s work is that for such a wildly imaginative writer, he also frequently uses material from his own life quite directly, and the two nestle side-by-side very easily.

Ice by Anna Kavan

One of the most mysterious and unlikely great novels I know, Kavan’s steely gothic allegory of both inner and out catastrophe is told from the point of view of a perfect son-of-a-bitch, a kind of surrealist’s James Bond type. I always picture him played by Jeremy Irons, circa Dead Ringers.

JC: Kavan’s male narrator describes a nightmarish ice-bound world, with a pale woman at its center. As you pointed out in your introduction to the fiftieth-anniversary edition of Ice, episodes in the novel could coexist easily with the works of Edgar Allan Poe, Kobo Abe, Kazuo Ishiguro and J.G. Ballard’s Crash. At one point Kavan’s narrator muses, “Her face wore its victim’s look, which was of course psychological, the result of injuries she had received in childhood; I saw it as the faintest possible hint of bruising on the extremely delicate, fine, white skin in the region of eyes and mouth. It was madly attractive to me in a certain way.” It’s as if Kavan, the female author, created a mirror image of herself as viewed by the narrator (and by his “double,” the Warden). Might this be considered a subversive refraction of the “male gaze”?

JL: I like that suggestion very much, even as I suspect Kavan would wonder what the hell we were talking about. To the extent that I can grasp her very opaque and cryptic personality through the time I’ve spent with her work, Kavan seems to me to have generated Ice from a deeply self-alienated position. She’s a true Surrealist, like some of those others you mention, yet unlike a writer like Ballard, she didn’t become more lucid or accessible as she progressed through her writing life—she grew more or more gnomic and allegorical.

Bleak House by Charles Dickens

Is there an earlier example of a man writing in first-person from a woman’s point-of-view than Dicken’s Esther Summerson? (Her chapters alternate with those of a characteristically omniscient third-person.) Or a more uncomfortable place for the practice to originate, if this is where it did? Esther’s absurdly self-effacing—but, then again, Dickens always traffics in such extremes of innocence, and his books improbably rise to the richest level of our experience of humanity despite—or because?—of this. As it develops, Esther turns out to be both an early version of “unreliability”, but also of the psychological type we now call “passive-aggressive.” I don’t know if she’d count among anyone’s favorite of Dickens’ characters, and yet Bleak House is many people’s favorite among his books (don’t believe me, believe Mary Gaitskill, Stephen King, and Vladimir Nabokov).

JC: An intriguing choice. Can you give examples of Esther’s “unreliability?”

JL: Oh, now I’m in trouble. As I’ve discovered working with students, “reliability” and “unreliability” in first-person is one of those oasis-type things—it only resolves into clarity in the middle distance, then evaporates the closer to it you push. I guess I see a sort of historical hinge-point in the use of narrators who claim not to be part of the story they’re telling: up to Somerset Maugham, who uses the method again and again, you can sort of believe them; after The Great Gatsby, never again. But in Esther, Dickens destroys my neat generalization, because she’s one of the earliest examples of a narrator who makes that claim, and she’s misleading about the extent and nature of her role in the story. If that doesn’t make her “unreliable” in the full Ford Madox Ford sense, it points the way.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·