Chaos is merely order waiting to be deciphered.

*

“[Saramago’s] prose is open to philosophical and psychological speculation as well as to homely folk wisdom, and its flights into the impossible are balanced by a feeling for the daily routines and labors that compose, for most of humanity, the substance of existence. Saramago is, in the not uncommon fashion of Latin intellectuals, an avowed Communist; his sympathy for workers broadens and solidifies his fictional thought-experiments.

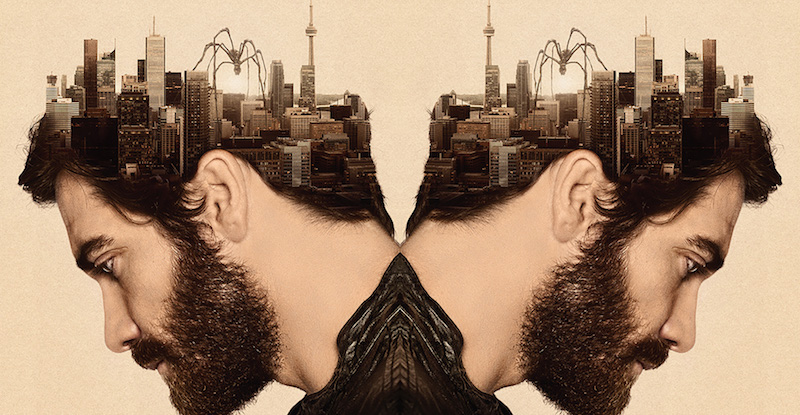

His new novel, The Double, deals with white-collar workers: the thirty-eight-year-old hero, the impressively named Tertuliano Máximo Afonso, teaches history in a secondary school; the divorced Tertuliano’s present lady friend, Maria da Paz, works in a bank; Tertuliano’s double, António Claro, acts in minor movie roles under the name of Daniel Santa-Clara; his wife, Helena, works in a travel agency. Their interactions and confusions, as intricate as those of a French bedroom farce, are scrupulously placed within the confines of working days and seasonal vacations, just as the waking nightmare, for Tertuliano and António, of confronting an exact physical duplicate is set in a sufficiently persuasive (though unnamed) metropolis of five million people, with their automobiles, their apartments, their anonymity. The wildly ramifying plot has an improvised air but proves to be tightly knit, constructed toward a stark dénouement.

…

“…unlike Dostoyevsky’s The Double and Poe’s ‘William Wilson,’ Saramago’s Double does not wrap the perception of a double in the protagonist’s delusional pathology or a suggestion of an inner self projected outward. The similarity objectively exists, down to the men’s moles and fingerprints, and has the comedy of, in Henri Bergson’s formulation, ‘something mechanical encrusted upon the living.’ Cloning, one letter away from clowning, affords us a smile as well as a shudder. Tertuliano’s double, unlike William Wilson’s, is not a whispering voice of conscience; António Claro is a bit actor in movies turned into videos, a habitual seducer, a karate expert (he is stronger than Tertuliano, but not apparently more muscular), and a heel, who totes a gun—in short, a bad actor. The reader shares the hero’s desire that he be erased. The novel, with its farcical elements, does not quite deepen into the dizzying vortex of identity issues that may have been intended; it remains more comic than not, and lacks the unforced momentum and resonance of Blindness, which, like Camus’s The Plague, allegorizes societal breakdown and a basic fear. Most of us are afraid of going blind; being duplicated is a relatively minor worry.

Yet Saramago has a questing and well-stocked mind, amiably engaged in the patient investigation of human nature. To bulk out the lean diagrammatics of his plot, with its mere four principals, he ruminates on the vagaries of language and the difficulty of applying common sense to our actions. Both are aspects, perhaps, of the same problem, human irrationality. Human beings are too complex and conflicted for words.”

–John Updike, The New Yorker, September 27, 2004

*

“The title of this new novel by Portugal’s Nobel Prize winner will very likely draw a sigh of despondency from many a reader. The conceit of the double has become something of a literary cliché, used repeatedly as a handy plot device from Plautus’ Amphitryon through Dumas and The Man in the Iron Mask to Dostoyevsky and Nabokov. Yet José Saramago has flogged new life into what might have seemed a dead horse. His take on the theme is clever, alarming and blackly funny, although he spins out to more than 300 pages a tale that Borges would have elegantly dispatched in three.

Saramago is not known for his lightness of touch. Blindness, surely his masterpiece so far, is a truly frightening account of what happens to so-called civilized values when a mysterious affliction strikes everyone in the world blind, except for a single person. In even his bleakest works, however, there is a note of dark laughter—the same note that sounds through Kafka, Céline and Beckett, who are Saramago’s direct literary ancestors. He has Kafka’s petrified detachment, Céline’s merry ferocity and the headlong, unstoppable style of the Beckett of Malone Dies and The Unnamable. All this may make his new book sound daunting. Although it is elegantly translated by Margaret Jull Costa, The Double isn’t the easiest read, yet it is engrossing and even, in its way, a page turner.

…

“One of the pleasures of the book is the way Saramago faithfully follows the relentless logic of the situation he has devised. When the two men meet, it is at once apparent that they are indeed doubles—that is, they not only look alike, but are identical, down to the moles on their forearms and the date of their birth. Immediately, existential questions are raised. Which of them, Tertuliano worriedly wonders, is the original and which the duplicate? … This mathematical quality is the book’s chief weakness. The trouble with self-consciously existential novels such as The Double is that the characters tend to be ciphers, as determined and robotic as the exemplars in one of those math questions from our school days so that we care for them not much more than we did for those imaginary figures trudging their undeviating way across the pages of our textbooks.

Tertuliano, absurdly named after a Carthaginian theologian, and António Claro, with his false beard and his empty revolver, are about as engaging as two peas in a pod. If Saramago believes what he has his omniscient narrator declare—that ‘every ordinary person is unique, truly unique’—he might have devoted some writerly energy to making his characters more lifelike. Even doubles will be different in their hearts.”

–John Banville, The New York Times, October 10, 2004