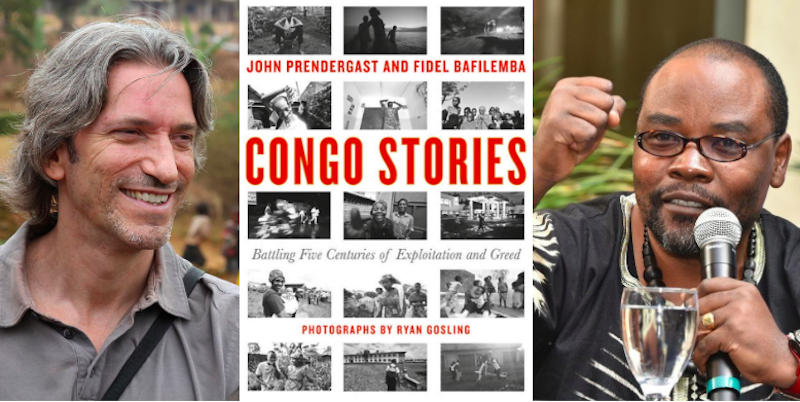

John Prendergast and Fidel Bafilemba’s Congo Stories is published this month. They share five books about the Congo with Jane Ciabattari.

Spectacle by Pamela Newkirk

Spectacle tells the story of Ota Benga, who was kidnapped from Congo and displayed first at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis and then in a cage at the Bronx Zoo.

Jane Ciabattari: Newkirk writes of Benga’s captor, Samuel Phillips Verner, the son of a wealthy slaveholding family from South Carolina, “Three decades after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, Verner continued to see potential in Africans as ‘the great coming laboring class of the world.’” How did the shocking and shameful treatment of Benga reflect the attitudes in the US at that time?

John Prendergast & Fidel Bafilemba: With the backdrop of the brutal colonial exploitation of Congo, and in the aftermath of transatlantic slavery in the U.S., there was a widely perceived and even accepted orthodoxy of the superiority of the white race. In this particular case, people profited from “proving” the inferiority of Africans, and Ota Benga’s saga perpetuated and provided space for racist theories that were considered mainstream at the time and continue to percolate even today. There were books in the late 1800s and early 1900s like Charles Carroll’s The Negro a Beast and Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman which portrayed Africans as part animal, prone to anger. There was speculation that Ota perhaps was the “missing link” between man and ape. A respected Harvard professor, Louis Agassiz, argued that blacks were a different species, a “degraded and degenerated race.” The Bronx Zoo’s cofounder, Madison Grant, wrote The Passing of the Great Race, a book which called for removing “inferior races” from America over time through mass sterilization and other methods. Hitler was deeply impressed with Grant’s work, often quoting him and reportedly writing a letter to Grant saying that “the book is my Bible.”

Ota became an overnight sensation in America when he was put on exhibit in the Monkey House of the Bronx Zoo, his companions at times being an orangutan, a chimpanzee, and a parrot. Ota was displayed in a metal cage in the Monkey House, wearing a coat and white trousers. The exhibit broke attendance records for the zoo. Newkirk writes, “Benga became the object of pointing fingers, audible gasps, and bellowing laughter… For the twenty-five cent admission fee and a five-cent ride on the subway, they could see what until now they had only read about: a genuine African ‘savage.’” The zookeeper “cheerily referred to him as ‘the little African savage’ and insisted that Benga ‘has one of the best rooms in the primate house,’” and he soon had bones displayed in the cage “to suggest cannibalism.”

Spies in the Congo by Susan Williams

Spies in the Congo uses previously classified documents to reveal how the U.S. was able to secure and extract most of the world’s high grade uranium from Congo for the development of the atomic bombs dropped on Japan.

JC: “The most important source of uranium is Belgian Congo,” Alfred Einstein wrote to FDR in August 1939. Williams describes the spycraft through which the US extracted the raw material for atomic bombs, and also the dismal conditions in Congo’s Shinkolobwe mine, where workers were exposed to radiation without protection, leading to birth defects and cancers. Williams also writes, “The moral authority of the struggle against fascism was not applied to the inequalities and injustice in the Congo.” What is the legacy of this today?

JP & FB: Aside from the multi-generational health defects and legacies, US corporations and consumers continue to greatly benefit from the exploitation of Congo’s vast natural resource wealth. Many of our most essential products—phones, computers, cars, etc.—source many of their most essential raw materials from Congo. And the terms of trade are more akin to terms of plunder.

King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild

One of the most compelling history books ever written, this book probably influenced ours more than any other.

JC: Which of the issues most troubling in Hochschild’s book persist today? And how has the future evolved in areas described in Congo Stories?

JP & FB: The most dramatic element of Hochschild’s book was the human toll resulting from the plunder of ivory and rubber from Congo’s vast territory. It is estimated ten million Congolese perished as a result of King Leopold’s violent extraction of these highly valued resources. Fast forward a century, and a war in eastern Congo fueled in large part over the violent competition for control over the mineral resources powering our most essential electronics products took over five million Congolese lives in a devastating repetition of history.

Dancing in the Glory of Monsters by Jason Stearns

The best insights into the deadliest war globally since World War II, which was fought on Congo’s soil, and in particular Rwanda’s role in it.

JC: Stearns calls the Congolese wars since 1996 “stories within stories,” and asks, “How do you cover a war that involves at least twenty different rebel groups and the armies of nine countries, yet does not seem to have a clear cause or objective?” Stearns talks to the perpetrators from nine countries, the survivors, the witnesses, child soldiers. Which of his insights do you consider most valuable?

JP & FB: Stearns’ assessment of the complex politics and financial interests driving many of the competing factions is one of the most insightful analyses of Congo’s complicated stew of local and international actors. Because he has spent so much time on the ground there, speaks a few of the languages, and cares so much, he has been able to get access to inside information like few other contemporary observers.

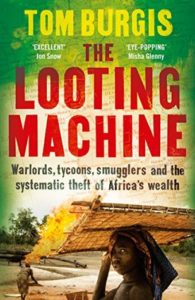

The Looting Machine by Tom Burgis

The Looting Machine is not solely about Congo, but it highlights the mechanisms by which countries like the Congo are looted for their natural resource riches.

JC: Burgis, who reported for the Financial Times from Africa for eight years, declares Africa’s “troves of natural resources”—with $333 billion in fuel and mineral exports in 2010 alone—a curse. He describes, as his subhead tells us, the “Warlords, Oligarchs, Corporations and Smugglers” who have stolen Africa’s wealth. His book came out in 2015. How have the last several years affected his analysis in the Congo? The same? Worse? Better?

JP & FB: Some of the spectacularly corrupt deals made, broken, and re-made in Congo since 2015 simply confirm Burgis’ theses involving the violent kleptocratic behavior of the Kinshasa regime and its international commercial collaborators. The exciting and hopeful variable, though, involves the extraordinary level of organization by Congolese civil society against these unfair economic arrangements, and a small but growing international movement, led by students, in solidarity with Congo’s activists. Their efforts have resulted in legislation forcing companies to reveal where and how they access their raw materials from Congo, major corporate behavioral change, and sanctions against key Congolese kleptocrats and their international partners. Finally, there is a consequence for the “looting machine” that the Congo represents, as Burgis calls it. Finally there is a challenge to that extraordinary, 500 year history of unparalleled exploitation of Congo’s vast resource base. Finally, people and companies who have benefited in the US and Europe are saying enough is enough, and trying to alter that devastating historical legacy. As Congo braces for more instability around an election, it’s important to remember that at a certain fundamental level, change is coming. It won’t be in a straight line or overnight, but the comeback has begun.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·