Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, a new feature in which books journalists from around the US share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recents gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic from a different part of the country, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

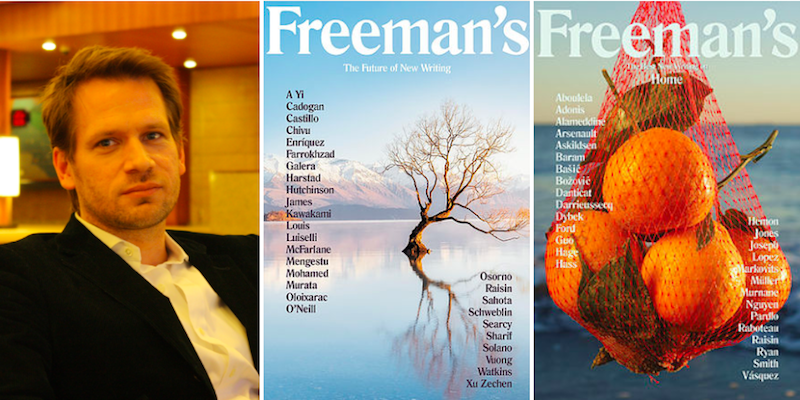

This week we spoke to Freeman’s editor and former National Book Critics Circle President John Freeman

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

John Freeman: The House on Mango Street, by Sandra Cisneros. What a warm and beautiful book this is, so gentle with its technical virtuosity—it is called a “coming-of-age” novel, but has a book weaved so seamlessly between poetry and prose and autobiography?—and wise. Immensely wise. I think books that contain wisdom are the most interesting to review because they force you as a critic to deal with the mysterious gap between craft and force of meaning. You also cannot hold them without being changed. I would have loved to have put this book into a reader’s hands. Clearly, it doesn’t need my help, but if I could go back in time, this is where I’d go.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

JF: Unheralded is a hard one. It did not go unnoticed that a psychoanalyst writing under the name of Jeremiah Moss published Vanishing New York, a loving and cranky tour that swerves through the destructive path of New York’s gentrification craze, clocking the knish shops, actual speakeasies, and real communities that have been erased by the wave of bubble cash that has coursed through the city. Still, I wish it had received more attention. I love this book partly because I see in its pages the ghost city in which I arrived. The bakeries and old stoop-sitters and hoarder emporiums. But I also appreciate Moss’ anger and rage against riches, which to me feels like one of the best parts about New York—its distrust of the greed of some of its citizens. I dearly hope that spirit won’t go the way of Chumley’s as we surf this latest absurd ride of the latest bull market. Without it New York becomes just another mirage.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

JF: That you turn to criticism if you are failing as a writer. I think the only reason to do this job is love, and sometimes you write criticism as you are starting out in respect of your craft, not against it. For instance, many of the critics I was on the book critics circle board with in the mid-to-late 2000s with—Rebecca Skloot, Maureen McLane, Lev Grossman, David Orr, Donna Seaman, and others—have gone on to write extraordinary books. Powerful books that have carved a deep path through readers. When they worked primarily as critics I think all of them were working out the aesthetics they would take to their books. I know that’s what I was doing.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

JF: The internet was a massive and in many ways destructive force on criticism. I do not for a second lament the broadening of access to writing platforms, but I do despair that with the demise of newspapers fewer people are reading book reviews. Look at the sales of literary titles, it has never been so feast or famine. I think this dynamic has to do with the relative lack of reviews out there. Yes, there are people blogging or tweeting or posting photos on their social media feeds, all of which is great—literary culture contains much more than reviews, that’s what Lit Hub in part celebrates—but when you can’t count on smart, career critics being out there to make sense critically of what a book is and means before a large general audience, as critics once did, I think we are the poorer for it.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

JF: Zadie Smith (whose new collection of essays, Feel Free, comes out in February) is one of the most lucid thinkers in the essay form alive today. Her taste is unpredictable and stylish, and she is at once fabulously eclectic in her influences and starchy in her requirements for pleasure. I wish she reviewed more, but I also wish she wrote more stories. It is exciting, though, that one of the world’s best fiction writers takes this part of the craft so seriously. Like James Baldwin, Eudora Welty, John Updike, and Mary McArthy, this puts her in good company.

*

John Freeman is the editor of Freeman’s, a literary biannual published in seven countries around the world. His books include How to Read a Novelist, Tales of Two Cities, and Tales of Two Americas. Maps, his debut collection of poems, was recently published by Copper Canyon Press. The former editor of Granta, he is now executive editor at Literary Hub and teaches at the New School and New York University. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, and Tin House, and been translated into more than twenty languages.

**

Previous entires in this series:

Editor, columnist, and NBCC board member Kerri Arsenault

The New Republic literary editor Laura Marsh

Heller McAlpin, contributor to Barnes & Noble Review, Washington Post, NPR, LA Times, and others

National Book Critics Circle President Kate Tuttle

Sam Sacks of The Wall Street Journal

Laurie Hertzel of The Minneapolis Star Tribune

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.