I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels—until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

*

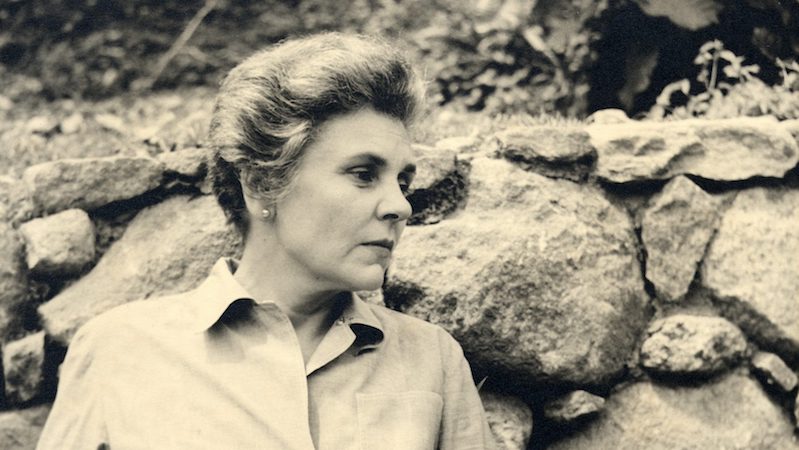

“One hopes that the title of Elizabeth Bishop’s new book is an error and that there will be more poems and at least another Complete Poems. The present volume runs to a little more than 200 pages, and although the proportion of pure poetry in it outweighs many a chunky collected volume from our established poets (Miss Bishop is somehow an establishment poet herself, and the establishment ought to give thanks: she is proof that it can’t be all bad), it is still not enough for an addict of her work. For, like other addicting substances, this work creates a hunger for itself: the more one tastes it, the less of it there seems to be.

From the moment Miss Bishop appeared the scene it was apparent to everybody that she was a poet of strange, even mysterious, but undeniable and great gifts.

…

“Her concerns at first glance seem special. The life of dreams, always regarded with suspicion as too ‘French’ in the American poetry; the little mysteries of falling asleep and the oddness of waking up in the morning; the sea, especially its edge, and the look of the creatures who live in it; then diversions and reflections on French clocks and mechanical toys that recall Marianne Moore (though the two poets couldn’t be more different: Miss Moore’s synthesizing, collector’s approach is far from Miss Bishop’s linear, exploring one).

And yet, what more natural, more universal experiences are there than sleep, dreaming and waking: waking, as she says in one of her most beautiful poems, ‘Anaphora,’ to ‘The fiery event / of every day in endless / endless assent.’

…

“This quality which one can only call ‘thingness’ is with her throughout, sometimes shaping a whole poem, sometimes disappearing right after the beginning, sometimes appearing only at the end to add a decisive fillip. In ‘Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance,’ which is possibly her masterpiece, she plies continually between the steel-engraved vignettes of a gazetteer and the distressingly unclassifiable events of a real voyage.

…

“As one who has read, reread, studied and absorbed Miss Bishop’s first book and waited impatiently for her second one, I felt slightly disappointed when it finally did arrive nine years later. A Cold Spring (1955) contained only 16 new poems, and the publishers had seen fit to augment it by reprinting North and South in the same volume. Moreover some of the new poems were not, for me, up to the perhaps impossible high standard set by the first book…A Cold Spring does however contain the marvelous ‘Over 2,000 Illustrations’ which epitomizes Miss Bishop’s work at its best: it is itself ‘an undisturbed, uncreating flame,’ which is a line of the poem. Description and meaning, text and ornament, subject and object, the visible world and the poet’s consciousness fuse together to form a substance that is undescribable and a continuing joy, and one returns to it again and again, ravished and unsatisfied.

…

“Her next book, Questions of Travel (1965), completely erased the doubts that A Cold Spring had aroused in one reader. The distance between Varick Street and Brazil may account for the difference not just in thematic material but in tone as well … Her years in the là-bas of Brazil brought Miss Bishop’s gifts to maturity. Both more relaxed and more ambitions, she now can do almost anything she pleases, from a rhymed passage ‘From Trollope’s Journal’ to a Walker Evanish study of a ‘Filling Station’; and from a funny snapshot of a bakery in Rio at night (‘The gooey tarts and red and sore’) to ‘The Burglar of Babylon,’ a ballad about the death of a Brazilian bandit in which emotionally charged ellipses build up a tragic grandeur as in Godard’s Pierrot le Fou.

Perhaps some of the urgency of the North and South poems has gone, but this is more than compensated by the calm control she now commands. Where she sometimes seemed nervous (as anyone engaged in a task of such precision has a right to be) and (in A Cold Spring) even querulous, she now is easy in a way that increased knowledge and stature allow. Her mirror-image ‘Gentleman of Shalott’ in North and South was perhaps echoing the poet’s sentiments when he said, ‘Half is enough.’ But the classical richness of her last poems proves that frugality need not exclude totality; the resulting feast is, for once, even better than enough.”

–John Ashbery, The New York Times, June 1, 1969