It was better than floods of misery that a son of her flesh had killed the sons of other mothers.

“This ‘Gary Gilmore book’ of Mailer’s was understood in a general way to be an account of or a contemplation on the death or the life or the last nine months in the life of Gary Mark Gilmore, those nine months representing the period between the day in April of 1976 when he was released from the United States Penitentiary at Marion, Illinois, and the morning in January of 1977 on which he was executed by having four shots fired into his heart at the Utah State Prison at Point of the Mountain, Utah.

It seemed one of those lives in which the narrative would yield no further meaning. Gary Gilmore had been in and out of prison, mostly in, for 22 of his 36 years. Gary Gilmore had a highly developed kind of con style that caught the national imagination. ‘Unless it’s a joke or something, I want to go ahead and do it,’ Gary Gilmore said when he refused legal efforts to reverse the jury’s verdict of death on felony murder. ‘Let’s do it,’ Gary Gilmore said in the moments before the hood was lowered and the muzzles of the rifles emerged from the executioner’s blind. Gary Gilmore’s execution in 1977 was the first in the United States in ten years, and the last months of his life were expensively, exhaustively covered, covered in teams, covered in packs, covered with checkbooks and covered with tricks, covered to that point at which Louis Nirer was calling Provo in a failed attempt to add some class to David Susskind’s bid for the rights, covered to that pitch at which the coverage itself might have seemed the only story.

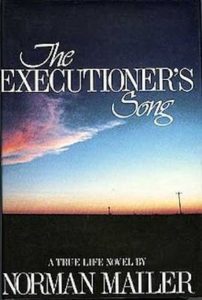

What Mailer could make of this apparently intractable material was unclear. It might well have been only another test hole in a field he had drilled before, a few further reflections on murder as an existential act … Instead Mailer wrote a novel, a thousand-page novel in a meticulously limited vocabulary and a voice as flat as the horizon, a novel which takes for its incident and characters real events in the lives of real people. The Executioner’s Song is ambitious to the point of vertigo…

…

“I think no one but Mailer could have dared this book. The authentic Western voice, the voice heard in The Executioner’s Song, is one heard often in life but only rarely in literature, the reason being that to truly know the West is to lack all will to write it down. The very subject of The Executioner’s Song is that vast emptiness at the center of the Western experience, a nihilism antithetical not only to literature but to most other forms of human endeavor, a dread so close to zero that human voices fadeout, trail off, like skywriting. Beneath what Mailer calls ‘the immense blue of the strong sky of the American West,’ under that immense blue which dominates The Executioner’s Song, not too much makes a difference. The place at which both Gary Gilmore and his Mormon great-grandfather came to rest was a town where the desert lay at the end of every street, except to the east. ‘There,’ to the east, ‘was the Interstate, and after that, the mountains. That was about it.’

In a world in which every road runs into the desert or the Interstate or the Rocky Mountains, people develop a pretty precarious sense of their place in the larger scheme. People get sick for love, think they want to die for love, shoot up the town for love, and then they move away, move on, forget the face. People commit their daughters, and move to Midway Island. People get in their cars at night and drive across two states to get a beer, see about a loan on a pickup, keep from going crazy. It is a good idea to keep from going crazy because crazy people get committed again, and can no longer get in their cars and drive across two states to get a beer. Nicole Baker, Gary Gilmore’s true love, got committed the first time at 14. April Baker, Nicole’s sister, had been a ‘little spacey’ ever since she got bad-tripped and gang-banged when her father was on leave in Honolulu. ‘I am a split personality,’ April said when she was asked about the July night in Provo when she went to the Sinclair service station and the Holiday Inn with Gary Gilmore and he seemed to kill somebody. ‘I am controlling it pretty good today.’

…

“These women move in and out of paying attention to events, of noticing their own fate. They seem distracted by bad dreams, by some dim apprehension of this well of dread, this ‘unhappiness at the bottom of things.’ Inside Bessie Gilmore’s trailer south of the Portland city line, down a four-lane avenue of bars and eateries and discount stores and a gas station with a World War II surplus Boeing bomber fixed above the pumps, there is a sense that Bessie can describe only as ‘a suction-type feeling.’ She fears disintegration. She wonders where the houses in which she once lived have gone, she wonders about her husband being gone, her children gone, the 78 cousins she knew in Provo scattered and gone and maybe in the ground. She wonders if, when Gary goes, they would ‘all descend another step into that pit where they gave up searching for one another.’ She has no sense of ‘how much was her fault, and how much was the fault of the ongoing world that ground along like iron-banded wagon wheels up the prairie grass.’ When I read this, I remembered that the tracks made by the wagon wheels are still visible from the air over Utah, like the footprints made on the moon. This is an absolutely astonishing book.”

–Joan Didion, The New York Times, October 7, 1979