Alas, the heart is not a metaphor, or at least not always a metaphor.

*

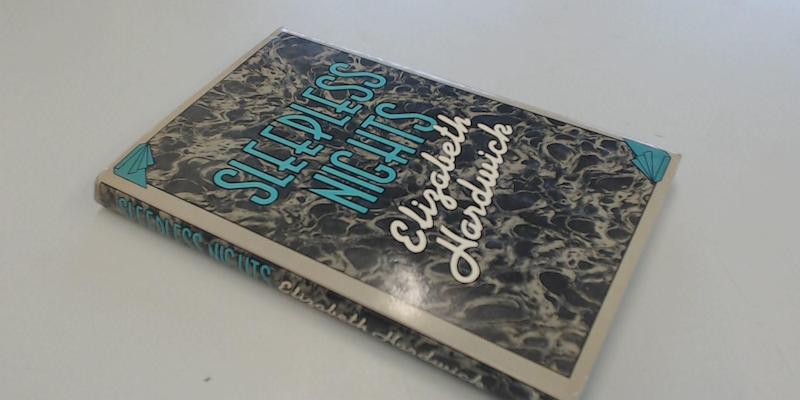

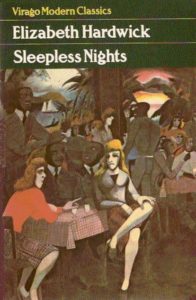

“‘I have always, all of my life, been looking for help from a man,’ we are told near the beginning of Elizabeth Hardwick’s subtle new book. ‘It has come many times and many more than not. This began early.’ . . . Sleepless Nights is a novel, but it is a novel in which the subject is memory and to which the ‘I’ whose memories are in question is entirely and deliberately the author: we recognize the events and addresses of Elizabeth Hardwick’s life not only from her earlier work, but from the poems of her husband, the late Robert Lowell. We study in another light the rainy afternoons and dyed satin shoes and high-school drunkenness of the Kentucky adolescence, the thin coats and yearnings toward home of the graduate years at Columbia, the households in Maine and Europe and on Marlborough Street in Boston and West 67th Street in New York. We are presented the entire itinerary, shown all the punched tickets and transfers. The result is less a ‘story about’ or ‘of’ a life than a shattered meditation on it, a work as evocative and difficult to place as Claude Levi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques, which it oddly recalls. The author observes of her enigmatic narrative: ‘It certainly hasn’t the drama of: I saw the old, white-bearded frigate master on the dock and signed up for the journey. But after all, “I” am a woman.’

This strikes an interesting note, a balance of Oriental diffidence and exquisite contempt, of irony and direct statement, that exactly expresses the sensibility at work in Sleepless Nights.

“She has chronicled again and again the undertow of family life, the awesome torment of being a daughter—an observer in the household, a constant reader of the domestic text—the anarchy of sex. She has illuminated lives traditionally misrepresented as tragic instances of the way all women live. In Seduction and Betrayal, for example, she located Virginia Woolf’s special and claustral narrowness, her aggravated femininity, less in her situation as a woman in estheticism and androgyny of Bloomsbury; she saw the source of Sylvia Plath’s destructiveness not in her time and gender but in her ‘lack of national and local roots,’ her ‘foreign ancestors on both sides,’ her peculiar and, once one has had it pointed out, quite unmistakable deracination.

This is all very original and interesting, and so is Elizabeth Hardwick’s radical distrust of romantic individualism, her passionate apprehension of the particular havoc that a corrupted individualism can play with the lives of women. Women adrift, in Elizabeth Hardwick’s work, indulge a fatal preference for men of bad character. Women adrift take dancing lessons, and end up on missing-person reports.

Perhaps no one has written more acutely and poignantly about the ways in which women compensate for their relative physiological inferiority about the poetic and practical implications of walking around the world deficient in hemoglobin, deficient in respiratory capacity, deficient in muscular strength and deficient in stability of the vascular and autonomic nervous systems. ‘Any woman who has ever had her wrist twisted by a man recognizes a fact of nature as humbling as a cyclone to a frail tree branch,’ she observed in an essay on Simone de Beauvoir some years ago, an assertion of ‘woman’s difference’ at once so explicit and so obscurely shameful that it sticks like a burr in one’s capacity for wishful thinking.

“The method of the ‘I’ in Sleepless Nights is in fact that of the anthropologist, of the traveler on watch for the revealing detail: we are provided precise observations of strangers met in the course of the journey, close studies of their rituals. These studies take the form of vignettes, recollections, stories that at first offer no sustaining thread … We are shown music teachers fallen on old age and poverty, cleaning women and their stubborn diseases, breasts hacked off, rashes, degeneration of the kidney, husbands with blood clots and felony convictions. We are shown women who survive and women who do not. We are shown Billie Holiday in 1943. We are shown women of ‘mad strength, hideous endurance, hostility, nightmares,’ women who live on to ‘wander about in their dreadful freedom like old oxen left behind, totally unprovided for.’ We are shown women who do not account to men, men who do account to women, children who refuse telephone calls from their parents, disarray and derangements of every kind. ‘If only one knew what to remember or pretend to remember,’ the curator of these memories frets at the outset of Sleepless Nights. Make a decision and what you want from the lost things will present itself. You can take it down from the shelf like a can. Perhaps.’

…

“The fieldwork proceeds. The meticulously transcribed histories begin to yield a terrible point, although not one that would astonish our mothers and grandmothers. In the culture under study, life ends badly. Disease is authentic. The freedom to live untied to others, however desired that freedom may be, is hard on men and hard on children and hardest of all on women. ‘Why is it that we cannot keep the note of irony, the jangle of carelessness at a distance?’ the narrator of this extraordinary and haunting book asks toward the end of her reflections. ‘Sentences in which I have tried for a certain light tone—many of those have to do with events, upheavals, destructions that caused me to weep like a child.’ Oh yes.”

–Joan Didion, The New York Times, April 29, 1979

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.