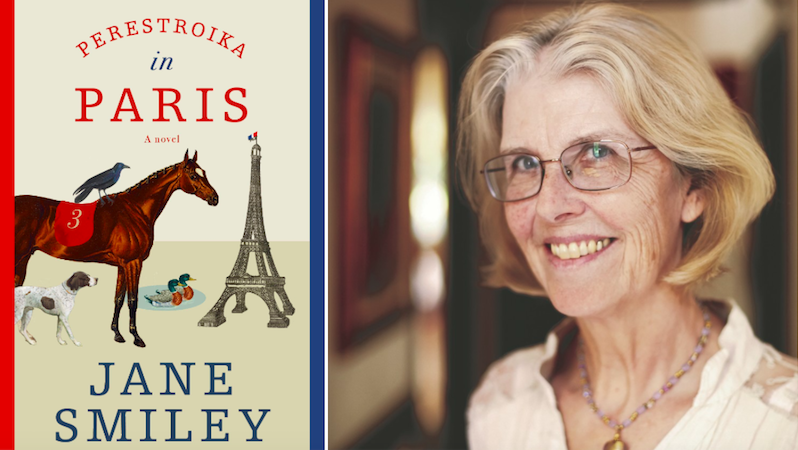

Jane Smiley’s new novel, Perestroika in Paris, is published today. She shares five novels by Emile Zola, which she calls “my introduction to the real Paris,” adding, “The nineteenth-century English writers I have always loved are Charles Dickens and Anthony Trollope. Emile Zola is the French combination of the two—as sociologically astute as Dickens, and as psychologically astute as Trollope, with a special talent for depicting landscapes and setting.”

La Curee (The Kill)

Zola published La Curee when he was about thirty-one. In it, he explores the destruction, or reconstruction, of Paris in the 1850s and 1860s, when many buildings and neighborhoods gave way to updated avenues. He focuses on the way that speculators bought up old houses cheaply and then sold them for profit when the lots were needed for the building schemes. He brilliantly understands both the necessity and cruelty of the accelerated changes brought about by the modernization of France in the mid-nineteenth century.

Jane Ciabattari: Aristide makes financial moves that would seem familiar to speculators today; using money from his wife Renée’s dowry, and insider information from his job in the surveyor’s office, he invests in apartments in areas about to be transformed by boulevards, then invents high-rent tenants to increase his profit. It helps that he also has inside information on two of the bureaucrats who oversee his compensation. “The Empire was on the point of turning Paris into the bawdy house of Europe,” Zola writes. “The gang of fortune-seekers who had succeeded in stealing a throne required a reign of adventures, shady transactions, sold consciences, bought women, and rampant drunkenness.” How close to truth was Zola’s depiction?

Jane Smiley: I have no idea, but what matters in a novel is not whether you are completely accurate, but rather whether you can come up with a depiction, a set of characters, and a plot that is plausible and reflects what you, the author, and other people you know think is true. La Curee was accurate enough that its serial publication was stopped, though not publication of the book. Zola recognized that the destruction of impoverished neighborhoods had several purposes and, according to Brian Nelson, one of them was to make it easier to put down rebellions by widening the streets and making impoverished neighborhoods more accessible. Even so, the reconstruction of Medieval cities to make them conform to the industrial era has to have been a dilemma because how the citizens (much larger populations) would be provided for had to be taken care of.

Le Ventre de Paris (The Belly of Paris)

Imagine Les Halles, the central food market in Paris. Imagine injustice suffered by a man who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Imagine that man, in the middle of the night, draped over a wagon bringing piles of turnips* into Paris from the countryside. And everything spreads out from there, into households all over Paris, some where elegant cuisine is the norm and others where anything someone can manage to get is all there is to eat.

JC: Zola crafts a series of tableaux at Les Halles as carefully wrought as paintings. “Salad herbs, cabbage-lettuce, endive….with rich soil still clinging to their roots, exposed their swelling hearts; bundles of spinach, bundles of sorrel, clusters of artichokes, piles of peas and beans, mounds of cos-lettuce, tied round with straws…” “salmon that gleamed like chased silver, every scale seemingly outlined by a graving-tool on a polished metal surface…” “the blushing peaches of Montreuil, with skin as delicate and clear as that of northern maidens, and the yellow, sun-burnt peaches from the south, brown like the damsels of Provence.” How does Zola’s portrait of abundance and appetite set the stage for his story?

JS: Le Ventre de Paris continues with the dilemma of supply. Les Halles caters to the greed of the Bourgeoisie for everything luxurious, including foods that are both delicious and prized, but even as he writes about what is available and how it gets there, Zola stimulates the appetites of not only his famished characters, but also the reader. This is a Paris we know, a place where trying out new and exclusive dishes is a treat of a lifetime, a place where just walking around and having a look is a thrill. The problem is exemplified in Au Bonheur de Dames.

Une Page D’Amour (A Love Episode)

This one is set across the Seine, in Passy, an affluent suburb, and told from a woman’s point of view. One thing she loves to do (and Zola loves to do) is stare at the evolving ugliness and beauty of the city across the river. When I read it, I see sunshine pouring through her window, lighting up the sky and the glittering roofs of Paris.

JC: “It was like the open sea, with its mysterious never-ending waves,” Zola writes. “Paris was unfolding, as vast as the sky.” And it’s always out of reach for Hélène, a widow with a sick twelve-year-old daughter whose crises drive this story. How does Paris fit into her yearnings?

JS: As in all of the Rougon-Macquart books, yearnings are multiple. Helene wants love, she wants prosperity, she wants the best for her daughter, she wants something new and interesting, she wants to get out of the house. But because she is a woman and a mother, the things she wants are not compatible—she can’t devote enough attention to both her daughter and her love life, and she is not going to get money without a wealthy suitor. I think this is a wonderful depiction of the dilemmas of being a woman in the nineteenth century, of doing your best with what you are given, and then seeing that tragedy results. Zola’s empathy for Helene is unusual for a nineteenth-century male author, and one of the reasons I love it.

Au Bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Paradise)

Amazon in the mid-nineteenth century! What we would call a department store is putting the local shops—drapers, dressmakers, shoemakers, weavers, you name it—out of business by organizing everything a fashionable woman might one in one large emporium, cutting the prices to lure in the customers, and then selling the leftovers cheaply to less wealthy customers. The young woman who sees the goods in the shop windows in the first chapter can’t resist the temptations they represent and that is why Jeff Bezos is the richest man in America.

JC: The department store tends to replace the church, Zola wrote in his research notes for this novel. “It marches to the religion of the cash desk, of beauty, of coquetry, and fashion.” His tale of the development and opening of one of Paris’s original department stores portrays its owner, Octave Mouret, as a genius at seductive selling. What drives his customers? Novelty? Accessibility?

JS: What draws the customers is, first, the advertising—that is, the figures in the windows wearing the clothing that customers on the street are intrigued by—already made, already attractive. Then the customers enter, and find cheap, convenient abundance. Selling is Mouret’s first priority, before profits, because he knows that buying can be addictive. In some ways, he can do what chefs do—show what can be done with raw ingredients that makes them elegant, attractive, and socially desirable.

L’Argent

Zola had a theory of how modern urban life works. It took him twenty volumes to fill in the blanks and let it play out through the lives and points of view of fifty-six characters. The driving force for almost all of the characters (though some more than others) is wealth and poverty, and the willingness and ability of some people to manipulate Capitalism (and the market) according to their own desires. He considered ruthlessness and kindness to be both nature and nurture, and he also explores genetics while he explores booms, busts, disasters. He always writes through his characters, giving the reader psychological insights as well as sociological ones. For many of them, only money matters, and yet money is never enough to satisfy them.

JC: Zola returns to the speculator Aristide in L’Argent, tracking him through an international scheme–founding a bank, attracting investors, reaching astronomical share value only to face a fall. Published in 1891, L’Argent is still one of the best novels about the financial world ever written (along with Theodore Dreiser’s 1912 novel The Financier). Why do you think so few contemporary novelists explore the world of finance, central as it is to our lives today?

JS: My guess is that the literary world has become so spread out that writers are not often in personal contact with financiers as they were in the past, when many writers lived in New York or Paris or London, and perhaps had gone to school with friends who became bankers or stockbrokers. We know in some ways how it works, but since capitalism is largely the same as it has always been, it seems both boring and irredeemable. I did try to explore the issue in my recent trilogy, The Last Hundred Years, but, say, around the time of the 2008 bust, it was nonfiction writers who were paying the most attention to Wall Street corruption (which was profoundly similar to the corruption in L’Argent). It’s also true that it’s been 150 years since Zola wrote L’Argent and capitalism and corruption seem to be set in stone now.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.