“I want to see your brains scattered all over your friends’ clothes, son. I want you to die for me.”

*

“Reflexively you blink from the sting of the dark, smoky surroundings and lick your lips to wipe away the taste of the cheap Scotch, as the sweet sounds of an alto saxophone whine up out of the pages of this richly atmospheric detective novel of the ’40s. Within the first 50 pages, Walter Mosley takes us through the back door of a little market at the corner of Central Avenue and 89th Place in Los Angeles and into an illegal black nightclub:

When I opened the door I was slapped in the face by the force of Lips’ alto horn. I had been hearing Lips and Willie and Flattop since I was a boy in Houston. All of them and John and half the people in that crowded room had migrated from Houston after the war, and some before that. California was like heaven for the Southern Negro. People told stories of how you could eat fruit right off the trees and get enough work to retire one day. The stories were true for the most part, but the truth wasn’t like the dream. Life was still hard in L.A., and if you worked every day you still found yourself on the bottom.

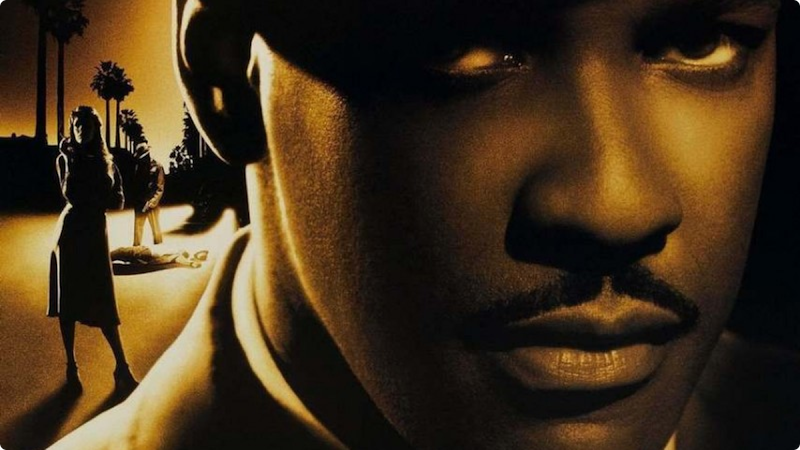

Ezekiel (Easy) Rawlins goes into John’s speak-easy to find out if anyone has seen Daphne Monet, a white woman who likes to hang out in black jazz clubs. Easy is a World War II vet who just lost his job at a defense plant and has to make some quick money to meet the mortgage. Most of his friends are black and poor, but DeWitt Albright, a white man wearing a linen suit with a Panama straw hat, pays him generously to find Daphne. As experienced mystery readers might predict, this simple assignment plunges Easy into a complicated series of intrigues involving other rich white men, other women, more money, and a remarkable number of dead bodies.

“Devil in a Blue Dress honors the hard-boiled tradition of Hammett/Chandler/Cain in its storyline and attitude, but Mosley takes us down some mean streets that his spiritual predecessors never could have because they were white. The insightful scenes of black life in 1948 provide a sort of social history that doesn’t exist in other detective fiction, and they lend an ambiance that heightens this story of crime and violence. Like the best of the ‘noir’ storytellers, Mosley’s strength is in his dialogue. He has a confident, perfect-pitch ear for nuances of speech that is astonishing in a first novel, and he knows how to set up a dramatic scene:

There was a slight commotion behind the football player and then a Panama hat appeared there next to him.

‘Excuse me,’ Mr. DeWitt Albright said again. He was smiling.

‘What do you want?’ the footballer asked.

DeWitt just smiled and then he pulled the pistol, which looked somewhat like a rifle, from his coat. He leveled the barrel at the large boy’s right eye and said: ‘I want to see your brains scattered all over your friends’ clothes, son. I want you to die for me.’

The large boy, who was wearing red swimming trunks, made a sound like he had swallowed his tongue. He moved his shoulder ever so slightly and DeWitt cocked back the hammer. It sounded like a bone breaking.

“Mosley was born four years after the year when his novel takes place, but apparently he listened closely to the stories his father told when he was growing up in Watts. He re-creates the era convincingly, with all of its racial tensions, evoking the uneasy combination of freedom and disillusion in the post-war black community and revealing a tough, fresh perspective on Los Angeles history.

He accomplishes all this in the context of a fast-moving, entertaining story written with impressive style. This is the kind of book that leaves you yearning to read more about Easy Rawlins’ adventures. Not surprisingly, the dust jacket notes that Mosley is busy writing a sequel. I’m willing to bet that Easy never goes back to work in that defense plant. He has a long, active career ahead of him as a private eye.”

–Digby Diehl, The Los Angeles Times, July 29, 1990

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.