Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to Oakland-based writer and critic Ismail Muhammad

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

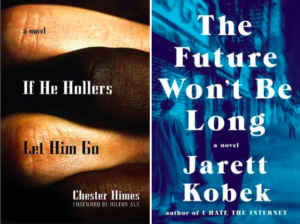

Ismail Muhammad: Probably Chester Himes’ corrosive race-noir novel If He Hollers Let Him Go. I first read it about a decade ago, and I return to it on a nearly annual basis because it’s such a strange melange of genre fiction, social realism, and psychological astuteness. To top it all off, it’s a seminal novel of black Los Angeles. A detective thriller without a detective and no mystery to unravel, If He Hollers tells the story of Bob Jones, a black Midwesterner who’s recently arrived in World War II-era Los Angeles so he can take advantage of new opportunities for black laborers in naval shipyards. Unfortunately, the opportunities for advancement turn out to be more meager than he expected: a racist union excludes Bob and his peers, and constant exposure to racist mistreatment puts Bob on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Meanwhile, his fascination with a white coworker named Madge puts his life in danger. Himes spins a familiar tale of the bitterness and paranoia that racism can breed in its victims, and Jones’ slow descent in self-destructive behavior will be familiar to anyone who’s read Richard Wright’s Native Son. But what really draws me to If He Hollers is the way Himes uses noir’s dark cynicism in order to evoke the sense of conspiratorial danger that accompanies racial paranoia. I’ve always admired how he uses noir as a tool to portray Los Angeles from a black perspective; it’s an unexpected genre mash-up that presaged Himes’ success as a master of detective fiction. I feel like this book must have been a bizarre outlier in 1945: in a year when America won World War II and assumed its place as an exceptional superpower, Himes’ novel demands that we pay attention to the prejudice that undergirded American power.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

IM: Jarett Kobek’s 2017 novel The Future Won’t Be Long transfixed me. Kobek returns to two characters has written about before—Adeline, the artist who was the protagonist of 2016’s I Hate the Internet, and her friend Baby. Following Adeline and Baby as they make their way through the 1980s New York art world, The Future is a bizarre novel that features Kobek’s signature tendencies towards internet-influenced digression, and it bears a resemblance to early novels like Moby Dick in its desire to encompass the entire world within its pages. Kobek often breaks the book’s narrative momentum in order to insert historical case studies, seemingly random anecdotes from Adeline and Baby’s lives, and the kind of editorializing that made I Hate the Internet so popular. Maybe that tries some readers’ patience, but I found it riveting. There’s just a sense of openness to the world that pervades the entire book.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

IM: When I got started, the greatest misconception I had about what it means to be a critic was that a critic knew everything, and simply brought that knowledge to bear on whatever they happened to be writing about. Being a critic has been much more about learning—from the authors I’m reading, conversations I have with other critics, and other readers’ observations—than knowing. Every time I write a review or an essay, I feel like my writing has everything to do with exploration, and the privilege of getting to learn in public.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

IM: Social media has augmented the role of the critic. Does anyone think of critics in such lofty terms as those that Ralph Ellison, Lionel Trilling, or Susan Sontag operated on? Twitter and Facebook have eroded critics’ authority. What makes a few critics important when hundreds of other people are offering their own, often intelligent, ideas? Our job isn’t to tell people what to think, but to convene spaces—whether online or IRL—in which conversation and thought can happen.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

IM: Undoubtedly Hilton Als. His writing has this quality of suppleness that I think is so brave. I guess it goes back to the privilege of thinking in public and convening space for thought. Als’ sentences don’t render judgement or analyze. They think aloud, oftentimes changing their minds mid thought.

*

Ismail Muhammad is a writer and critic based in Oakland, California. He’s a staff writer at the Millions, a contributing editor at ZYZZYVA, a board member at the National Books Critics Circle, and a Ph.D. candidate in the English department at U.C. Berkeley. In addition, he’s been a recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Emerging Critics Fellowship, a Simpson Family Literary Fellow, and a participant in the VONA 2017 workshops. His work, which focuses on literature, art, identity, and black popular and visual culture, has appeared in publications like Slate, New Republic, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Real Life, and Catapult. He’s currently working on a novel about the Great Migration and queer archives of black history. @trapmotives

*

· Previous entries in this series ·