Is there anything more thrilling than digging into a just-released book by an admired author?

In Context is an essay series in which critic Lori Feathers looks at the latest work of fiction by an established writer within the context of their overall body of work. Lori explores her subject’s oeuvre by identifying the writer’s themes and cultural resonance, discussing their literary technique, and revealing how the new book builds upon, or diverges from, their previous work.

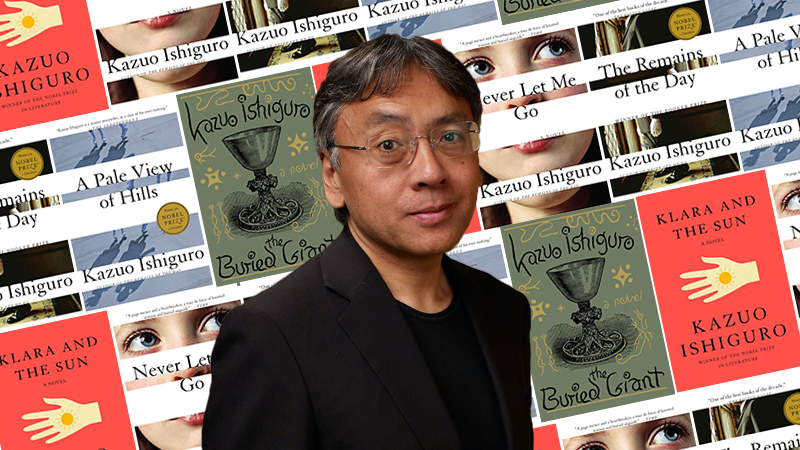

This week, Lori considers the novels of Kazuo Ishiguro.

*

In his eighth and latest novel, author Kazuo Ishiguro imaginatively explores what it means to be human. Klara and the Sun is narrated by AF Klara, an Artificial Friend (model B2, 4th series) manufactured to be a child’s companion. Klara walks, talks, and reasons much like a human. She is always helpful and cheery, as befits her intended function. As the novel begins Klara and a few other AFs are on display in a store showroom that looks out onto a busy city street. Through the window Klara closely observes the world outside: impatient taxis, stressed-out executives peering into their “oblongs” (cellphones), clustered tourists, and sweaty runners. In particular Klara keeps vigil on the daily trajectory of the Sun, which “gives nourishment” to her and her fellow solar-powered AFs.

After weeks on display Klara is purchased by Josie, a pale, thin teen who walks with a limp related to an unspecified illness. Josie brings Klara home to her comfortable house in the country where she lives with her divorced mother, Chrissie, and their housekeeper. Josie and Klara soon form a close attachment with Klara quick to learn everything about Josie so that she can be an excellent companion, including how to care for Josie on the days when she is ill. Josie’s best human friend is her neighbor Ricky, and the two often discuss the future and their plans to be together after they are grown and leave home.

But Ricky is different from Josie and the other kids who Chrissie wants Josie to befriend. Despite being really smart, Ricky is not “lifted,” that is, he did not undergo the gene editing procedure that Josie and most all of their peers have. (While not explicit, it seems that lifted kids are visibly distinguishable from those who are not.) There are health risks associated with gene editing—Josie’s older sister Sal died a few years ago of complications from it, and Chrissie suspects that it is the cause of Josie’s illness as well—but also harsh consequences for not having it done; namely, no college will accept Ricky and, as a result, his career prospects are limited.

Ricky’s mother feels guilty about not having Ricky edited, and although she made the opposite choice, Chrissie, too, feels guilt and remorse for proceeding with Josie’s gene editing despite what happened to Sal. Anticipating that Josie might soon die from her illness, Chrissie has devised a secret plan that she believes will help her endure the pain of losing Josie. Clues about Chrissie’s intentions are unveiled gradually and to good effect as the novel’s suspense builds.

Throughout his fiction Ishiguro brings into sharp focus those left behind in the wake of societal change. The novels are populated with characters who face their own obsolescence, who come to realize their faded relevance to the very social structures that once made them feel indispensable. Some, like Ogata-San in A Pale View of Hills, and Ono, who narrates An Artist of the Floating World, are stigmatized for their outdated political views and wartime activities in Japan. Others, like the butler Stevens’ father in The Remains of the Day and the married couple Axl and Beatrice in The Buried Giant, are dismissed as irrelevant because of their age. And then there are the narrators of Ishiguro’s dystopian novels—Kathy H. in Never Let Me Go and the robot Klara in Klara and the Sun—who become functionally obsolete when they have achieved their intended use: for Kathy H., having her body parts extracted as part of an accepted system of organ harvesting; and for Klara, serving as the companion to a genetically modified child.

Many of Ishiguro’s protagonists are boastful and self-important, and they sustain the expectation that they will always be held in the highest esteem. A smug arrogance defines many of the male narrators, in particular. Recollecting his days as a young artist Ono boasts, “I commanded considerable respect amongst my colleagues—my own output being unchallengeable in terms of quality or quantity.”

At times, a character’s faith in his ability to direct the course of events feels delusional or absurd, as with Christopher Banks in the novel When We Were Orphans. Banks is a London-based detective who grew up in Shanghai and decides to return as the city is roiled by combat between the Japanese and Chinese in the early days of WWII. “You see, it’s always been my intention to return to Shanghai myself. I mean, to….to solve the problems there,” he says. Later, as he prepares to flee Shanghai with his lover he notes “…the assumption shared by virtually everyone here—that it was somehow my sole responsibility to resolve the crisis,” and he relishes “the astonishment that would soon appear on these same faces at the news of my departure—the outrage and panic that would rapidly follow.”

Klara, too, is convinced that she can alter fate, certain that only she knows what it takes to make Josie well again. With a singular purpose and despite the absurdity of her plan, she goes about trying to make it happen. Whereas Kathy H. in Never Let Me Go wants to believe that she and her friends somehow will be granted special permission to defer the extraction of their organs until they are older due to the fact that they attended Hailsham, an elite boarding school. For characters like Ono, Banks, Klara, and Kathy H., pride in their own abilities or status distorts their perception of the world and their place within it, making their narration doubtful in its accuracy but also fascinating for the reader in discovering how far the character’s perspective veers from reality.

The unreliability of memory is a recurring theme of Ishiguro’s. Often characters’ actual experiences are splintered with dream sequences and frayed memories so that the real and the imagined morph and combine, becoming difficult to distinguish. Such is the case in Ishiguro’s spectacular first novel from 1982, A Pale View of Hills, in which Etsuko, a middle-aged woman living in England, recalls her friendship with another woman, Sachiko, decades prior when the two were neighbors in Japan. Here the uncanny parallels between the two women’s experiences draw into question not only the credibility of Etsuko’s memory, but also whether Sachiko really existed at all. Ishiguro suggests the pliability of memory, its tendency to absorb the tint and hue of what we are feeling at the point in time we engage in the act of remembering.

In each of his novels Ishiguro draws attention to his characters’ failure to effectively communicate with each other, and it cannot be happenstance that Klara, a robot, speaks with a clarity and directness that stands in sharp contrast to that of the humans she encounters. Ishiguro brings Jamesian attention to the nuanced significance of verbal cues, pauses, and body language, while exploring the intention and effect of these better, perhaps, than any other novelist writing today. Nowhere is this more evident than in his exquisitely rendered novel Remains of the Day and the exchanges between gentleman’s butler Stevens and housekeeper Miss Kenton as they work together at an English estate during the interwar period. Their conversations, formal and painfully restrained, are implicitly charged with suppressed physical longing and unarticulated regret.

In other novels, such as The Unconsoled and When We Were Orphans, interlocutors misunderstand the meaning and context of what is said to them, and their conversations quickly spiral into mutual incomprehension. What is most surprising and unusual, however, is that the characters never admit their confusion nor make any attempt to correct how they have been misunderstood. This obfuscation creates an absurd and disorienting effect. In Never Let Me Go Ishiguro explores another type of communication—complicit silence. Here the Hailsham students are kept in the dark about what will become of them once they finish school. When the teacher Miss Lucy rebels against the school’s policy and begins to explain to her pupils what the future holds for them, the students do not want to discuss it. Suspecting just enough of the truth to sense that they would be upset by what Miss Lucy wants to reveal, they willfully avoid the topic and implicitly accommodate the veil of secrecy imposed by the school’s administration.

Yet for all of the instances where Ishiguro’s fiction demonstrates his contemplation and sensitive insight regarding the ways we communicate and misunderstand one another, many of the conversations in Klara, particularly among the adults, feel inauthentic and dissonant. And perhaps this is precisely Ishiguro’s point: the grownups in Josie and Ricky’s world have lost the capacity to truly connect with one another in any meaningful way because in order to survive in the new society they must extricate themselves from the emotions intrinsic to the human condition—the rational must suppress and conquer the sentimental. How ironic and fitting that it is Klara, a robot, who comes to understand what a fool’s errand this really is.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·