Is there anything more thrilling than digging into a just-released book by an admired author?

In Context is an essay series in which critic Lori Feathers looks at the latest work of fiction by an established writer within the context of their overall body of work. Lori explores her subject’s oeuvre by identifying the writer’s themes and cultural resonance, discussing their literary technique, and revealing how the new book builds upon, or diverges from, their previous work.

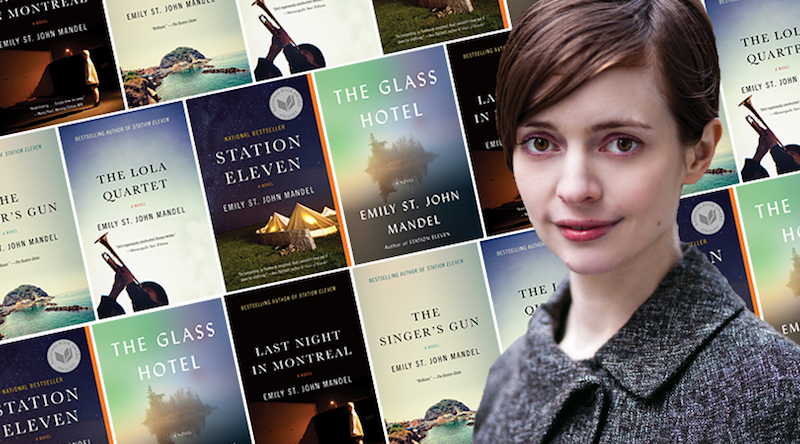

This week, Lori considers the novels of Emily St. John Mandel.

*

Canadian novelist Emily St. John Mandel is a portraitist of reinvented lives. Her characters are shapeshifters who create new identities, sever ties to home, and slide into worlds very different from those into which they were born. This process of becoming someone else, the provocation to transform, and the price it exacts are matters that Mandel captivatingly explores in each of her novels including her latest, The Glass Hotel.

Vincent, the female protagonist ofThe Glass Hotel, is named after the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay. Vincent’s mother tells her daughter that Millay transformed herself “by sheer force of will” from an impoverished girl brought-up in New England’s backwaters to an acclaimed poet at the center of New York City’s art scene. This narrative of how Millay remade herself serves as a talisman for Vincent throughout her life.

Vincent was born and raised on the tiny island of Caiette in British Columbia. When she is thirteen her mother disappears, presumed to have perished in an accidental drowning. Following a few years in Toronto taking college courses and doing odd jobs Vincent returns home and becomes a bartender at Hotel Caiette, the island’s newly-built luxury hotel.

Mandel situates her narratives around a mystery. In The Glass Hotel it is the sudden appearance of a threatening message graffitied onto the outside of Hotel Caiette’s glass wall while both Vincent and her brother Paul are working there one night. The meaning of the message and the motive behind it remain unresolved throughout much of the novel.

Later that same night the hotel’s owner, Jonathan Alkaitis, arrives from New York City where his lucrative investment business is based. He chats with Vincent for a while and eventually propositions her to leave Caiette and live with him in New York. To the wider world Vincent will be presented as his wife although they will not, in fact, be married. Recently widowed, Jonathan believes that the presence of a wife will provide a sense of stability to his investors.

Vincent likes Jonathan well enough and accepts his offer. Overnight she transforms herself from a bartender into the young trophy wife of a wealthy businessman, a metamorphosis that transports her to the “kingdom of money,” a world that Vincent never imagined for herself but one to which she easily succumbs:

It wasn’t the stuff that kept her in this strange new life…What kept her in the kingdom was the previously unimaginable condition of not having to think about money…If you’ve never been without, then you won’t understand the profundity of this, how absolutely this changes your life.

Jonathan, too, is very satisfied with the arrangement. As he sees it Vincent possesses a special pragmatic drive that enables her to become the very person that any given situation requires—in this case the glamorous wife of a prominent financier—without anyone doubting that she is perfectly suited to be just that.

The notion that identity is impermanent and malleable has always been fertile ground for Mandel’s vivid imagination: the girl Lilia (Last Night in Montreal) who for years repeatedly changes her name and appearance while she and her father are on the run; Anton (The Singer’s Gun) who refuses to return home from his honeymoon, instead settling down in an Italian village to avoid continued involvement in his family’s shady business; Gavin (The Lola Quartet) who leaves suburban Florida and moves to New York City in order to become a famous investigative reporter; and, Arthur (Station Eleven)—a small town guy who, after becoming a famous actor, turns every aspect of his life into a constant performance. These characters share with Vincent the impulse to rip free from the sticky adhesive of the familiar and to become someone else entirely.

But seizing the shortcut to a new life comes at a cost. For Vincent it is the burden of her considerable guilt. She legitimized her acceptance of Jonathan’s proposal by telling herself that if she refused it another woman would grab the opportunity in her stead. Much later she deeply regrets both her complacency in not wanting to know the source of Jonathan’s enormous wealth and her complicity in his corruption by pretending to be his wife.

In Mandel’s other novels characters justify criminal or immoral acts by convincing themselves that they had no choice. For instance, in The Singer’s Gun Anton wants to break free from his parents’ illicit business restoring and reselling stolen antiquities so he lies about receiving a degree from Harvard, convinced that it is the only way that someone like him, without a college education, can land a respectable office job.

Invariably the lies and misdeeds of these characters accumulate and grow until a point is reached beyond which it becomes impossible to reverse course or right the wrongs.

…this could still be undone. There had been two lapses now but turning back was still possible. There could still be an evening years or decades from now when he might look back at a strange period far earlier in his career, a few shadowy months…when he’d started to slide but pulled himself back just in time…(The Lola Quartet)

No matter how complete or seamless a person’s reinvention, her former, discarded life refuses to remain buried. Instead it clings to her present existence as a “shadow life” inhabited by ghosts from the past who appear and reappear, their presence an insistent reproach for relationships left unresolved, wrongs unredeemed.

How the boundaries that define present and past, performance and life, memory and invention blur together until their borders are difficult to distinguish is a persistent theme in Mandel’s work. Often her characters imagine alternate or counter-realities in which their own life’s course is fundamentally changed by reversing a single decision, foregoing just one act, or makingthe slightest alteration in circumstances.

…[Vincent] often found herself thinking about variations on reality…where she’d quit working at the Hotel Caiette and returned to her old job at the Hotel Vancouver before Jonathan arrived, for example, or where he decided to get room service that morning instead of sitting at the bar and ordering breakfast…None of these scenarios seemed less real…she was struck sometimes by a truly unsettling sense that there were other versions of her life being lived without her…

Mandel also interrogates the line that separates artistic creation and misappropriation. Many of her characters are artists. Some work as professional musicians, painters, and actors while others are amateurs like Vincent, who creates video art. When Vincent’s estranged brother Paul becomes renowned for his performance art, Vincent discovers that without her permission he has been using old videos that she filmed on Caiette as part of his show. Likewise, when Jonathan’s brother Lucas reluctantly agrees to sit for his portrait, Olivia paints the track marks on Lucas’ arm that he wanted to keep concealed—a theft of Lucas’ privacy. Both Paul and Olivia steal not just for the sake of their art but for personal gain, much like Vincent, Anton, and the other characters who lie and cheat in order to create their new selves.

Mandel’s novels examine how place affects characters’ perceptions. Many have wanderlust, rooted in a desire for anonymity or a feeling of alienation. They travel to suppress the pain of disappointment. Their peripatetic life is a physical expression of a restless quest for meaning. But no matter where they travel, they never find what they are looking for:

He pulled off the interstate into towns that all looked the same to him. He tried to find things to differentiate them, some kind of proof that he was passing through parts of three different states, but there was almost nothing. Only the names of the towns varied, and the towns were like envelopes with all the contents the same. (The Lola Quartet)

Others, like Vincent and Arthur (Station Eleven), grow-up in tiny, isolated towns where the possibilities are limited. They yearn to live in a city, to have access a large canvas in which to test themselves and experience life.

The scale of physical spaces also has significance in Mandel’s writing. It is refreshingly original that oceanic cargo ships are a recurring motif in her novels (interestingly, a number of characters connected to the shipping industry appear in more than one of Mandel’s books). After Vincent’s relationship with Jonathan abruptly ends, she takes a job as a cook on a cargo vessel, vowing never to live on land again. The ship’s extraordinary size and its intrinsic transience give a sense of unreality and impermanence to Vincent’s existence, as though she is unbound from life, adrift in a liminal space between land and water, life and death. The limbo between life and death is given further expression on board the ship when Vincent’s memories of her mother converge with appearances of her mother’s ghost.

The poem “Renascence,” by Vincent’s namesake Edna St. Vincent Millay, is narrated by someone who experiences all of the world’s sin and suffering and as a result, dies from despair. From her grave one day she hears rain pattering on the ground above her and realizes how much she misses the beauty of the natural world. Seized with a new, ardent desire to live she is reborn, possessed of a new appreciation for life. Mandel’s reference to Millay’s poem underscores the novelist’s extraordinary appreciation for the mutability of life and death and the perpetual transfiguring of self—a process that is divine in its imperfect incompleteness.

· Previous entries in this series ·