The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas,

a lonesome area that other Kansans call “out there.”

“The plains of western Kansas are even lonelier than the sea. Men, farm houses and windmills become specks against the vast sky. At night, the wind seems to have come from hundreds of miles distant. Diesel-engine horns echo immensity. During the day, one drives flat out through shimmering mirages. Highways all roll straight to the point of infinity on a far horizon. Tires click; tumbleweed rustles; Coca-Cola signs endlessly creak.

…

“To the Midwestern newspaper reader, the crime and its aftermath while awful enough, were not especially astonishing. Spectacular violence seems appropriate to the empty stage of the plains, as though by such cosmic acts mankind must occasionally signal its presence. Charlie Starkweather, accompanied by his teen-age lover, killed 10 people. George Ronald York and James Douglas Latham murdered seven. Lowell Lee Andrews, the mild, fat student with dreams of becoming a Chicago gunman, dispatched his father, mother and older sister with 21 bullets. Last May, Duane Pope, a clean-cut young football player, shot four people (three of them fatally) who were lying face down on the floor of a rural bank in Nebraska. Multiple murder is one of the traditional expressions of youthful hostility. To Truman Capote, the killings in western Kansas seemed less commonplace.

…

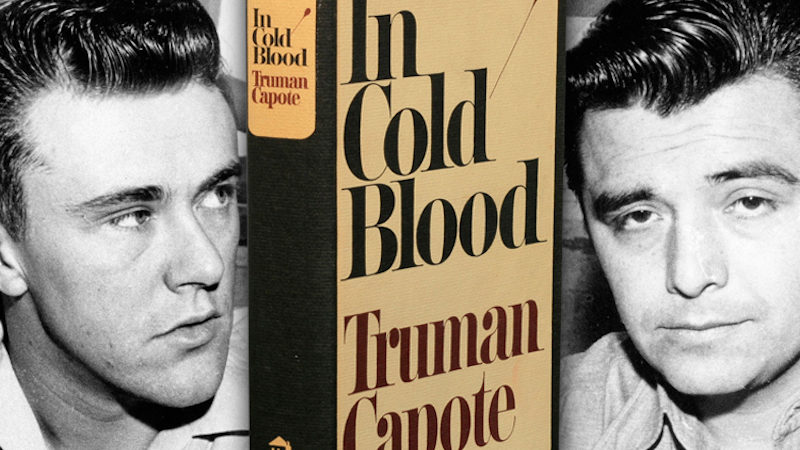

“With the obsessiveness of a man demonstrating a profound new hypothesis, he spent more than five years unraveling and following to its end every thread in the killing of Herbert W. Clutter and his family. In Cold Blood, the resulting chronicle, is a masterpiece—agonizing, terrible, possessed, proof that the times, so surfeited with disasters, are still capable of tragedy.

…

“As he says in his interview, with George Plimpton, he wrote In Cold Blood without mechanical aids—tape recorder or shorthand book. He memorized the event and its dialogues so thoroughly, and so totally committed a large piece of his life to it that he was able to write it as a novel. Yet it is difficult to imagine such a work appearing at a time other than the electronic age. The sound of the book creates the illusion of tape. Its taut cross-cutting is cinematic. Tape and film, documentaries, instant news, have sensitized us to the glare of surfaces and close-ups. He gratifies our electronically induced appetite for massive quantities of detail, but at the same time, like an ironic magician, he shows that appearances are nothing.

“In Cold Blood also mocks many of the advances (on paper) of anti-realism. It presents the metaphysics of anti-realism through a total evocation of reality. Not the least of the book’s merits is that it manages a major moral judgment without the author’s appearance once on stage. At a time when the external happening has become largely meaningless and our reaction to it brutalized, when we shout ‘Jump’ to the man on the ledge. Mr. Capote has restored dignity to the event. His book is also a grieving testament of faith in what used to be called the soul.”

–Conrad Knickerbocker, The New York Times, January 16, 1966

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.