In his forty-third year William Stoner learned what others, much younger, had learned before him: that the person one loves at first is not the person one loves at last, and that love is not an end but a process through which one person attempts to know another.

*

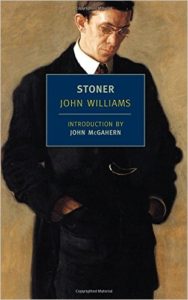

“The 50th-anniversary edition of John Williams’s Stoner comes garlanded with hyperbole. Bret Easton Ellis calls the novel ‘almost perfect.’ Morris Dickstein raises it to ‘perfect.’ Ian McEwan calls it ‘beautiful.’ Emma Straub dubs it ‘the most beautiful book in the world.’

The story of William Stoner, a professor of English at the University of Missouri who fails in his marriage and career ambitions, but accepts obscurity and loneliness out of devotion to teaching and love of literature, went unremarked on when it was first published in 1965. In the 21st century, however, it has become a literary phenomenon, first as an unexpected European bestseller and then as an American classic.

“But I am not a fan of Stoner. First, along with other female readers, I am put off by Williams’s misogyny…The worst of Stoner’s afflictions is his marriage. He is consistently rejected and irrationally sabotaged by his wife, Edith, who is portrayed as a neurotic harpy. Initially a sheltered society girl, shy and earnest about her duties to her husband, she is so sexually repressed that on their honeymoon she throws up when he embraces her…When Williams sent a draft of the novel to his agent Marie Rodell in summer 1963, she was uneasy about the wife’s character and wrote back that ‘Edith’s motivations’ need amplification. He made some changes in his account of the couple’s courtship, which he thought made Edith’s subsequent behavior “more believable.” But he makes no effort to explain her feelings; she remains shrewishly and selfishly indifferent to Stoner’s professional travails and personal disappointments. She seems to exist only to torment her husband.

“Now, strangely, he is a moving exemplar for many readers, who see him as an inspiring model of integrity who faces his sad life with unflinching courage and finds redemption in faithfulness to his ideals. They revere Williams’s artistry as a writer of restrained, unsentimental prose that carries great emotional weight. Rediscovered at a time when the humanities are in decline, academic jobs are scarce and teaching takes a back seat to blogging, the novel’s message of humble and heroic service to literature has obvious appeal for sorrowing humanists, too. Stoner, one critic writes, is the ‘archetypal literary Everyman.’

But Williams’s insistence on making Stoner a blameless martyr, rather than a man with choices, and denying him any ironic self-awareness about the causes of his Job-like misfortunes leaves the novel far from perfect.”

–Elaine Showalter, The Washington Post, November 2, 2015