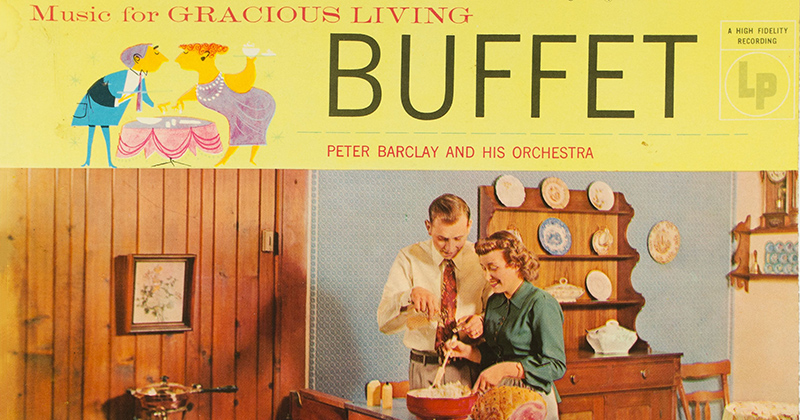

Record albums, as popular, mundane, and mass culture artifacts in postwar America, were designed to teach US citizens about ideal lifestyles, including family bonds and how to entertain at home, as well as how to travel the world. So, it wouldn’t be surprising to find that events overseas, after World War II and during the Cold War, influenced what our record albums communicate, especially given our sense that vinyl LPs of the time served as an essential information distribution format. And, indeed, in small and grand ways, from details of kitchen design to voices of the lunar landing, our records express, making subtle arguments for, the superiority of democratic capitalist freedoms in contrast with Soviet life.

Consider the American National Exhibition, held in Moscow in 1959: the trade fair, “designed by George Nelson, was intended to promote the comforts and contentment of a materialistic society as a contrast to the communist regime and lifestyle.” A film, Glimpses of the USA, by American design team Charles and Ray Eames, was shown on giant television screens. During the fair, the “rituals of family life were enacted four times a day with a wedding, a honeymoon, the backyard barbecue, and the country-club dance.” In these rituals, one finds notions of romance, love, individual freedoms, and family values, each of which figured in attempts to articulate and visualize aspects of US superiority over the gloomy communist alternative—often portrayed as disregarding aspects of individual attachment, desire, and welfare in favor of political and cultural ideology.

Historian Lizbeth Cohen has argued that the postwar rise of the “consumer republic” profoundly changed “America’s economy, politics, and culture, with major consequences for how Americans made their living, where they dwelled, how they interacted with others, what and how they consumed.” In particular, at midcentury, new forms of entertaining, listening, and watching emerged:

The legendary white middle-class family of the 1950s, located in the suburbs, complete with appliances, station wagons, backyard barbecues, and tricycles scattered on the sidewalks, represented something new. It was not, as common wisdom tells us, the last gasp of “traditional” family life with roots deep in the past. Rather, it was the first wholehearted effort to create a home that would fulfill virtually all its members’ personal needs through an energized and expressive personal life.

However, the midcentury was also an “age of anxiety.” The Cold War suffused contemporary living in the United States, and the American home was central to conflicting visions of a good life during a period dominated by dueling superpowers and concerns to “contain” Soviet Communism. Consumer goods occupied central roles on both sides of the Cold War propaganda battles. In this way, “the commodity gap took precedence over the missile gap.”

In the United States, individuals were understood to have the freedom to make their own lives, in part through their access to a wealth of available resources, including affordable consumer goods and services. The “sovereign,” or self-determining, choices they made among these available options marked a key distinction within US-Soviet propaganda battles: “Consumer sovereignty was the most popular Cold War wedge between east and west, one that—unlike the apocalyptic balance of nuclear terror—struck into the heart of everyday life.” Sociologist Don Slater argues that “the eminently modern notion of the social subject as a self-creating, self-defining individual is bound up with self-creation through consumption: it is partly through the use of goods and services that we formulate ourselves as social identities and display these identities.” In this sense, consumption and daily practices in a consumer culture brought the Cold War into the home.

In particular, the kitchen, a paragon of domestic comfort, family togetherness, and modern technology, “became one of the central sites of Cold War rhetoric.” During the infamous “kitchen debate” between US Vice President (and presidential hopeful) Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in 1959, “nuclear proliferation rhetoric moved to the domestic space and to the suburban home, as the two leaders tensely debated the merits of capitalism vs. socialism in front of a worldwide television audience at the inauguration of the American National Exhibition in Moscow.” Historians Ruth Oldenziel and Karin Zachmann, wrote about “kitchens as technology and politics” in a book on the Cold War kitchen. They argue that after the world witnessed Nixon and Khrushchev lingering over a display of lemon yellow General Electric appliances, some researchers claimed that regardless of Sputnik successes and other scientific advances, “from then on, technology was to be measured in terms of consumer goods rather than space and nuclear technologies.”

For the Soviets, investing in “technological systems” that would serve all citizens, such as buses, trains, housing programs, and childcare centers, stood against US Cold War emphasis on individual, and individually purchased, consumer goods, such as privately owned cars and suburban homes. Echoes of the related claims to lifestyle superiority can still be heard today, often connected to the same goods and services. We see then the strategic importance of focusing on certain consumer goods, and the contemporary consumer lifestyles these make possible—for example, the convenience, comfort, even glamour, of automobile ownership or the updated refrigerator—in midcentury media communications, and also why concerted efforts at communicating these messages might appear in the humble form of the LP record album cover.

A key tenet of Soviet Cold War propaganda maintained that the United States lacked a distinctive or historically developed culture of its own. Indeed, America was castigated as obsessed with trivial (and uncultured) entertainments, consumer choice, and ephemeral distractions—aspects of precisely those elements the United States engaged for Cold War cultural diplomacy and ideological defense. To counter such assertions, the United States harnessed key cultural forces of jazz, modern design, and abstract art, holding up each as a symbol of affluence, freedom, and individual expression. To be sure, modernism represented disparate movements within a variety of cultural arenas, tenuously linked together via a sense of rebellion against tradition. During the postwar era, however, “modernism took on new and surprising meanings due to the changing political and cultural environment, eventually being used in support of Western middle-class society.”

Modernism “illuminates both the Cold War ideology and the domestic revival as two sides of the same coin: postwar Americans’ intense need to feel liberated from the past and secure in the future.” For example, modern furniture was well-suited to a less formal era, and served to accommodate and display the new television and hi-fi sets that were becoming staples of the midcentury household. As Elizabeth Armstrong, curator of the noteworthy “Birth of the Cool” exhibit at the Orange County Museum of Art, observed in 2008, “Midcentury modernist architecture and design have been appointed as backdrops for and symbols of a confident urbanity, starring in Hollywood films and fashion shoots and used by high-end advertisers and mass commercial outlets to sell everything from luxury cars, credit cards, and investment services to vodka, sneakers, and blue jeans.” Of course, modernism had been recruited for this and more since its inception.

Cold War cultural skirmishes have been discussed in the context of art, film, furniture, jazz, magazines, books, radio, and popular exhibitions. Still, few accounts of modernism’s role in Cold War cultural diplomacy, cultural imperialism, pedagogy, and propaganda mention record albums. Yet, when looking closely at midcentury vinyl LPs, an overarching sense of how the Cold War trickled down into popular-culture artifacts becomes apparent. Although some albums specifically addressed military power and advanced technology, such as Air Power and X-15 and Other Sounds of Rockets, Missiles, and Jets, the larger battle over ideological, military, and political supremacy raging between the two super powers encroached upon the design, music, and marketing of mainstream, popular albums as well. Looking back at midcentury vinyl LPs today, evidence of Cold War rhetoric abounds: Cuban music, with bright, sensual covers, released before Castro; jazz albums adorned with abstract art; and lifestyle LPs that featured attractive images of appliance-filled kitchens all appear as subtle components of the ideological struggles of the era.

__________________________________

From Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America. Used with permission of MIT Press. Copyright 2017 by Janet Borgerson andJonathan Schroeder.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay[/caption]

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay[/caption]