This town is filled with echoes. It’s like they were trapped behind the walls, or beneath the cobblestones. When you walk you feel like someone’s behind you, stepping in your footsteps.

*

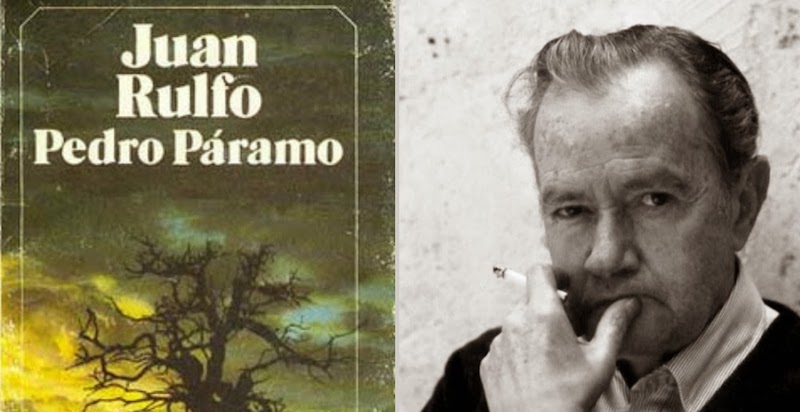

“When Susan Sontag, in her foreword to this book, calls Pedro Paramo ‘one of the masterpieces of 20th-century world literature,’ she is not being hyperbolic. With its dense interweaving of time, its routine interaction of the living and the dead, its surreal sense of the everyday, and with simultaneous—and harmonious—coexistence of apparently incompatible realities, this brief novel by the Mexican writer Juan Rulfo strides through unexplored territory with a sure and determined step.

Fulfilling a promise to his dying mother, Juan Preciado travels to her birthplace to search out his father, Pedro Paramo. But instead of the animated village of her memories, he finds Comala a place of death, surrounded by mirages. And Pedro Paramo? ‘Living bile,’ he is labeled by a fellow traveler, who then adds, confusingly, ‘Pedro Paramo died years ago.’

Did he? Perhaps. And perhaps he took the village with him: ‘I will cross my arms,’ he had said, ‘and Comala will die of hunger.’ We are in a couple of worlds here: the profane realm of Pedro Paramo and the crypt from which come the murmurings that eventually overwhelm Comala’s survivors until we can’t always differentiate between the quick and the dead, or judge when the former become the latter.

“A linear plot is as foreign to Rulfo’s novel as subtlety to an avalanche, yet the book is strangely accessible. The discordant assemblage of moments is so arresting that the characters and their nebulous entrances and exits resonate powerfully, while the land itself (the most powerful character of all) exerts an irresistible pull.

Pedro Paramo is particularly memorable. Manipulating those around him (even rebel bands fighting the Mexican Revolution) as if by divine right, he has enemies killed, beds any woman who momentarily strikes his fancy and marries for economic convenience.

Yet even this tyrant, so able to command his surroundings, cannot control his fate. Of all his women, the one he most cares about loses her mind and announces on her deathbed, ‘I only believe in hell,’ while his one acknowledged son falls off his horse and is killed.

Loss so dominates the novel that even the land becomes burned out and barren. Only fate continues unchanged; the little dramas played out under its constancy fade away until all that is left is the deadly murmuring. It’s a bleak but indelible picture.

“When it appeared in 1955, Pedro Paramo shook the foundations of Latin American literature, then marked (with obvious exceptions—Borges, for one) by a kind of straight-ahead realism that pushed against no barriers. It was as if William Faulkner had unleashed As I Lay Dying on a literary world ruled by James Fenimore Cooper.

Such has been the influence of Pedro Paramo that as tribute, Gabriel Garcia Marquez included a sentence from it in One Hundred Years of Solitude and, according to Ms. Sontag, knows the whole book by heart.

The novel has been available in English since 1959, though in a version that misses the spirit of the original. Having it now in all its depth and texture is a major event for which the publisher and the translator, Margaret Sayers Peden, deserve thanks.”

–James Polk, The New York Times, August 6, 1995

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.