(Children are, briefly, somewhat different.)

–John Berger, “Why Look at Animals?”

When I was in first grade, a migrating humpback whale swam seventy miles upriver from the San Francisco Bay and found itself marooned in a freshwater slough north of Rio Vista. The national papers filed dozens of stories about the whale—soon named Humphrey—and the nightly news checked in with his progress for nearly a month, with extended Humphrey segments on weekend shows like 60 Minutes. I caught as much of it as I could from my home on the other side of the country. The video footage rarely offered much—usually just shots of the small flotillas surrounding Humphrey, or of the people, both aboard and ashore, banging cookware to frighten the whale downriver. I remember one still image of a man in a fishing boat tossing buckets of salt water onto Humphrey’s back. Too lethargic to flip or spout, Humphrey was just a long, slick log floating near scores of excited humans. That was all I ever knew of him on earth.

This could be why I filed Humphrey the humpback into the same category as My Little Pony or the Easter Bunny. Nothing about the Humphrey tale was anything short of magic to me. When Peter Jennings said Humphrey’s name on the news, I ran into my living room with the same enthusiasm I felt upon hearing the Smurfs theme.

They finally got Humphrey to swim back to open water by plunging a high-tech speaker into the river and blaring the cries of feeding humpbacks, which he followed. These cries were described to me—by the news, by my teacher—as “song,” so my seven-year-old understanding was that this whale had been crooned to safety. I can still see the finale footage—how Disney-perfect it looked!—of the boats leading a shadow of a gigantic fish under the largest bridge I’d ever seen. They were all in a faraway land no one in my family had ever visited, and that whale swam home right under the most fantastic-sounding bridge: the Golden Gate.

Most of the animal world held for me this incorrect magic, which spurred me toward an impasse—an inability to note the contextual divide between the animals that shared our world and the ones that were invented to please me. At whatever moment of a child’s development that she learns to separate natural wonder and wondrous tale, something inside me misfired. Only from the distance of adulthood can I even see the disconnect, and I’m not sure if this is the case with other young children of my era, because I grew up alone.

I was born at the tail end of the 70s, four days before Easter, and all the cards sent to my mother were covered in pastel chicks and lambs. The nurses wrote my sex and my hospital ID number on cards with pink dancing bears, which they stuck to the bassinet and the door of our room. Someone gave me a stuffed hare in a navy vest that sits near me in early photos. In all these shots, I am a bleary-eyed, furry little thing.

[pullquote]”Once, and for a very long time, animals were crucial to human life; they surrounded people and culture in a close circle that connected to both the everyday and the spiritual.”[/pullquote]

My mother took me home in a receiving blanket patterned with geese in blue bonnets. She mailed announcements of my length and weight on cards bearing crewel-stitched puddle ducks. The early facts of my life were written into a book with a fat bunny on the cover. I slept in a yellow Beatrix Potter crib set, surrounded by Peter Rabbit, Tom Kitten, and Hunca Munca Mouse.

This was the year after critic John Berger published the first version of his “Why Look at Animals?,” an essay often hailed as a founding document in the field of animal studies. Berger’s essay begins by outlining a loss: once, and for a very long time, animals were crucial to human life; they surrounded people and culture in a close circle that connected to both the everyday and the spiritual. But, Berger says, due to the Industrial Revolution and the ripple effects of the 20th century, “every tradition which has previously mediated between man and nature was broken.” As Berger saw it, animals were no longer the “messengers and promises” of culture, or our partners in survival. Instead, they were available only as neutered pets, as kept zoo creatures, or as “commercial diffusions of animal imagery.” These commercial images, stuffed toys, and storybook animals aped “the pettiness of social practice,” Berger said, adding that “the books and drawings of Beatrix Potter are an early example.”

According to my Peter Rabbit baby book, the first song I could sing was “Old MacDonald,” and I knew the word “kitty” by the end of my first year. For my birthday, Mom baked a chocolate cake in the shape of a cat with uncooked spaghetti in the icing (for whiskers). By then, I’d tell any interested party what the kitty said, what the doggie said, even what the fishy said. In my crib at night, I watched a mobile of padded quadrupeds spin to “Farmer in the Dell.” My green bikini top was shaped into a pair of googly-eyed frogs, I wore a brown-checked dress covered in bespectacled owls to meet Santa Claus, and I was given for Easter a stuffed rabbit in a pink pinafore—my best friend, Tammy—that I rarely let go of through kindergarten.

I realize now that, growing up in a house shared only with two working adults, I was a fairly lonely girl, which left inside me a tender spot—not broken, just bruised—that I can still locate. When pressed, the lonely spot feels like being lost; it reminds me that, for years, I was the only member of my species (the species of modern kid). It’s a wonder this didn’t convince me that Humphrey, the only creature of his kind for miles, was a part of my real world. But the tender spot was most certainly soothed by the promises and messages of (what I thought were) animals. I obsessed over creature books, toys, and movies. The Poky Little Puppy taught me to read. Charlotte’s Web taught me that rats were gross and that my mother would die one day. Koko’s Kitten taught me that every creature just wants something soft to care about. I still can quote the majority of these animal stories from memory; they kept me company.

At night, after I cleaned my room by cramming all its loose contents in the hamper at the foot of my bed, I could hear my stuffed animals inside the box, whimpering in the dark. Alone in the yard, I often pretended I was an orphan in the wilderness. I’d splash around in the rain and find reasons to fall in the mud. I fantasized what kind of animal would find me and take me (perhaps literally) under its wing. Sometimes it was a natural animal, like a wild horse or a wolf, but just as often it was something more magical—a luck dragon or a white horse that could fly. They were all the same to me, of course.

The year of Humphrey, I turned seven and celebrated at a pizza parlor known for its “live” animatronic critter band. In the dining area, the robot animals performed at programmed intervals—a brown bear on drums, a gorilla on keyboards, a polar bear on guitar. A curtain drew around them at the pauses. I snuck behind it and looked up the pleated skirt of the tambourine player—a giant, deactivated cheerleader mouse. Her purple robot eyelids had frozen, half-raised, when she lost power.

*

The sharpest moment in “Why Look at Animals?” involves a glance between a beast and an earlier human. Berger is vague about where and when this might have taken place, but his man and animal, as they stare at one another, experience a deep understanding. They recognize both their mutual power and their separated secrets. Berger calls their connection an “unspeaking companionship” grounded in the lack of a common tongue. It allows human and animal to live along “parallel lines,” during which the human feels the animal’s gaze enhancing “the loneliness of man as a species.”

Berger says “the look between animal and man . . . may have played a crucial role in the development of human society.” We were inspired by their proximity—both what we knew of them and what we didn’t. And while the product of this isolating gaze gave animals a spiritual power and a place in human art, their nearness as both livestock and predator kept them “real” and vital. “They were subjected and worshipped, bred and sacrificed,” Berger says. Thanks to that Bergerian gaze, animals covered the major components of human life—both religious and quotidian, both biological and mythic. Because of that look, a lion could become for humans both a threatening neighbor and a god. That look assured that animals “belonged there and here.”

But according to Berger, this gaze is something I would never myself experience, because the real animals had been extracted from my own here long before I arrived. I wholeheartedly recognize this. Here for me was but a synthetic wilderness. Here was Minnie Mouse jamshorts and Thundercats bathtub toys, plush mammals I could take to bed and tell my secrets to. But, still, my here was never without an animal representation. More than people and more than machines, false animals inhabited my field of vision (even though they could never return my gaze). It is important for me to remember that these animals were, essentially, fact-less. But because they were omnipresent and because they outnumbered everything else, this was the universe—an absolute onslaught of fake animal presence was every fiber of my here. I wonder if Berger ever took into account what might happen to future generations when those “commercial diffusions” of animal shapes became available to young minds at such a fever pitch.

In his essay, the affected 20th-century humans are nondescript capitalists, but it seems we should take them all as fully formed. In Berger’s thinking, little space exists for children. The bereft “now” of his essay is full of adults who stand within a generation of the earlier human-animal connection. But what happens when a person is born after the mess we were in circa “Why Look at Animals?” What happens when she begins not just forming herself, but finding herself among a sham menagerie?

[pullquote]”My sense of story, art, imagining, the words for writing, the ways of coping—they all come from the experiences that my phony zoo contributed to my early youth.”[/pullquote]

I’d argue that my animal imaginings essentially were spiritual, and that they made an intense there for me via the thousands of hours of cartoons and books, the Wonderful World of Disney, and my own goofy solo play. It certainly wasn’t the there on which entire cultures were built (was it?), but I believed it like a zealot. Despite the fact there were no real ones around me, I used these warped ideas of animals to help me solve problems, I sang animal songs to soothe myself, and I certainly spoke to them in a kind of prayer. My faith—and I was reared far from religion—was this blank space in which the late 20th-century “animals of the mind” were free to romp as I saw fit. I now have a spiritual there, and it is my only one, warped as it may be, where Berger says nothing exists anymore. My sense of story, art, imagining, the words for writing, the ways of coping—they all come from the experiences that my phony zoo contributed to my early youth.

My mom took me to the National Zoo in DC, where 1,000 other onlookers and I watched a giraffe give birth (“Can you believe we were here when it happened?”). At the Bronx Zoo, I rode a camel. My dad put me on his shoulders at a low-rent South Carolina zoo and I poked at an ostrich with a stick until it bit my Keds sneaker. At Zoo Atlanta’s week-long summer camp, I watched Wild World of Disney videos in the lab behind the reptile building, where one of the yellow snakes had the same name as me. We were gently led through parts of the flamingo enclosure and we even played red rover in the empty polar bear exhibit. Running and yelling where the polar bears roamed each morning felt like touring a celebrity home.

Most of these zoos had undergone renovations into our current breed of animal tourism, their verdant habitats and outdoor viewing pavilions replacing the concrete cages and tire swings of earlier times. These zoo designs were no longer the meager “theatre props” Berger decried in the late 70s, with only “dead branches of a tree for monkeys, artificial rocks for bears, pebbles and shallow water for crocodiles.” This is not to say, of course, that they were any more natural.

According to Berger, “The zoo cannot but disappoint.” It only presents “lethargic and dull” specimens removed not only from their natural environments, but also from any natural drive or individual interest. They cannot inspire, or even exchange that crucial glance with the humans who visit them. There are no “parallel lines” between human and animal life in a zoo, because, as is the case with house pets, the animal life has become so dependent on humans that it is no longer viable alone.

But I do not recall a disappointment like Berger describes, because at the zoos, I was often too busy to look at any animal for very long. Here is something else Berger was probably unable to foresee: my visits in the 1980s were to zoos that had marginalized the marginalized animals. Along with creating more convincing habitats, these new zoos built scores of distracting “discovery kiosks” and activities—rock walls, coloring stations, kiddie trains—that lined the paths from one enclosure to the next. At dozens of sidewalk carts, you could buy T-shirts or concentrated orange juice in a plastic container—shaped like an actual orange! It was more like visiting a theme park than a menagerie.

No longer was the main purpose to see, as Berger says, the “originals” of the stuffed mammals from our bedrooms. I was there to gallop about and play, to be my own animal. The kiddie games ran interference for the zoo creatures which, for me, were more like the robot critter band at that pizza place. They were an underscore to a party, the jazzy accompaniment to an afternoon outside with horseplay, a picnic, and maybe a present or two.

Where Berger says every zoo-goer raised on Peter Rabbit asks herself, “Why are these animals less than I believed?” a decade later, I think I’d have been more likely to ask, “Why are these animals even here?”

The section on zoos is the grand finale of the essay; Berger concludes with the lamentable image of a crowd at an animal cage, standing before a creature that will not look at them in any meaningful way. The crowd, then, can only look at each other as “a species which has at last been isolated.” Here he says, is the failure of zoos. Perhaps this explains why, by the time I arrived at one, they’d given me other things to do. And, it must be said, several things to buy. Maybe this is the real question kids of my era should have asked when they skipped into the zoo: “Since commerce took real animals from me, shouldn’t it have to make for me a viable replacement?”

*

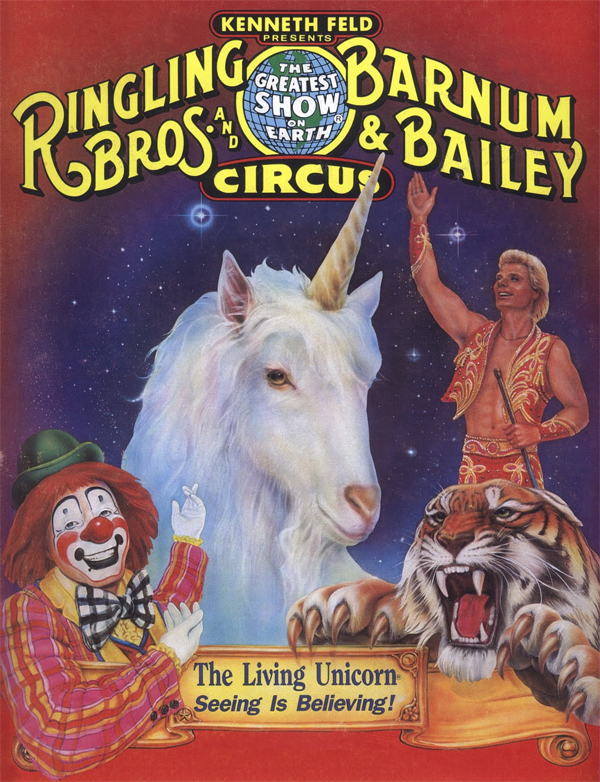

That same year as the Humphrey story and the zoo camp, my grandparents took me to the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. This was their year of Lancelot—“the Living Unicorn,” as he was billed on the 1985 souvenir program. I bought the program with three dollars of my own money and, after the circus, thumbed through it for weeks until the glossy pages fell to pieces. It said the Living Unicorn had just wandered into the big top one day the previous year, provenance unknown. Lancelot was ageless; there were no facts to weigh him down other than the fact that, according to the program, he ate rose petals for dinner. In the full-color photographs, he usually stood next to a spangly, Miss-America-cute woman, his long white hair—not so much a mane as a suit of poodle curls—gleaming and very possibly permed.

The horn at the top of his head was prodigious: twice as thick as that of the title character in The Last Unicorn. It was also covered in opalescent pink paint, trunking up from Lancelot’s forehead in a glittery shaft. In one photograph, he appeared with two children about my age. The blond boy in the photo smiled out toward the photographer, but the little girl next to Lancelot stared right at the unicorn with unabashed awe, like she’d forgotten all about the person taking her picture. Lancelot himself gazed into the middle distance, looking like a little, white Rick James. Who knows what he was thinking.

The program also featured a pullout poster that I taped to my closet door. It was a Lisa Frank-style portrait of Lancelot in a hot pink frame, above the caption “I Saw the Living Unicorn!” I’m not certain how many differences I noticed, back then, between the illustrated poster unicorn and the photographed one. But now, it’s obvious that the drawn unicorn is horsier, with a straight-up mane, a fuller muzzle and a longer, broader neck. The eyes are much less hircine, and they stare straight into the viewer.

At the circus, Lancelot didn’t gallop in; he rode. His entrance was on a hydraulic float trimmed in Grecian curlicues, with a curved dais at the top of it, slathered in gold paint. On the dais was a waving handler, dressed sort of like Glinda the Good Witch, who stood beside Lancelot. The unicorn himself had a tiny gold pedestal atop the dais, on which he could only arrange his front two feet.

A follow spot stuck to the vehicle as it zoomed around the ring; Lancelot stood erect, but sort of jostled in the motion of the float. Schmaltzy orchestral music boomed from the Civic Center speakers. From my seat, Lancelot was little more than a white furry blob. But when his shellacked horn, firm and proud on his cranium, caught the spotlight, everyone around me inhaled. He was much smaller than a horse—maybe pony-sized—which, being small myself, I found exciting.

I now wonder why the circus didn’t just strap a horn to an actual pony. They could have easily used showbiz magic to sell that trick from an arena-sized distance. But the circus was working a different angle with this critter that, even from yards away, was no horned horse. Perhaps they needed a horn that would look more legitimately rooted in photo close-ups. They knew I would obsess over that program, so they wanted a unicorn that read biologically true at home, away from the smoke and spotlight. But I think it’s more likely that they wanted to surprise us over anything else, even if that surprise involved a ridiculous specimen. It’s brilliant circus logic: that this jarring, not-horse-body was so weird, it would make sense when you learned it subsisted on flower petals. In other words, the circus hoped the more unnatural Lancelot looked, the happier I’d be.

What I recall feeling at that matinee is an aching deep in that tender, only-child place inside myself. It softened the suspect details of Lancelot’s freaky body. Under the “tent,” I had a foundational understanding something was fishy about that unicorn, but still, I ached for him. The emotion, for me, wasn’t about his realness; it was about sitting (relatively) near something that represented offsite magic. This is a reverse of Berger’s zoo animals—failed attempts at real versions of stuffed bedroom toys. Lancelot was the glorious opposite: a fake spectacle at the center of the ring that confirmed all my homespun, isolated imaginings to indeed be believable magic. Wild and insane Lancelot was before me; he could be both visited and dreamed about. The unicorn goat was, for me, both there and here.

Along with sensing, and then ignoring, that the unicorn was phony, I also knew it was probably some kind of victim, though even that didn’t deter my pleasure. I could not yet grasp how costly a real animal’s presence in my imagination could be. Of this I am the most ashamed, because I know a version of that ignorance still lives in me. I didn’t grasp, or I refused to consider, what kind of subjection was possible—the various ways humans open up and alter other creatures.

[pullquote]“Lancelot himself gazed into the middle distance, looking like a little, white Rick James.”[/pullquote]

The tales of Beatrix Potter never mention that billy goats are born with their horn-buds loose, floating right under the skin for the first week of their lives. It never occurred to me that a person might vivisect a newborn goat—graft the buds from their rightful place above the eyes to the frontal bones of the skull. Ten more days into the baby goat’s life, this process would be impossible, as by then the skull has ossified. But an enterprising human with a fresh goat on her hands can divide the kidskin forehead into four dermal flaps and rearrange them—in a process called “pedicling”—so that when the horns form, they fuse over the pineal gland and erupt as a single keratin pillar.

How could I ever have imagined that, even as obsessed with fantasy as I was? Where in my wildest seven-year-old dreams was US Patent #4,429,685, which legally awards authorship of “a method for growing unicorns” to a separatist religious leader turned veterinary surgeon named Timothy G. Zell, alias Otter G’Zell, alias Oberon Ravenheart?

After a New York City performance, someone called the ASPCA about Lancelot. The FDA performed a careful examination and declared him a perfectly healthy, if deformed, goat. Another phone call was made to the New York Consumer Protection Board to challenge whether Lancelot could legally be billed “unicorn.” The circus responded with a full-page ad in the Times—“Don’t Let the Grinches Steal the Fantasy!”—and refused to admit that it bought Lancelot from Zell for a six-figure sum. Lancelot lasted another national tour, and then disappeared from the circus, who hasn’t mentioned him since.

Of course, none of this controversy was in my head when I saw Lancelot. I was just one of the thousands of Americans born in 1978 that watched a surgically altered goat ride a golden chariot around their local civic center. But here I am, 30 years later, trying to explain what happens when I look at animals, and the creature that palpitates my tenderest spot is that hot mess of an animal—over the humpback whale, the baby giraffe, or the snake with my own name.

Maybe this is the coda to the final zoo scene of “Why Look at Animals?,” as this is what an animal consciousness can now become. Four decades past Berger, the animal of my mind is a gaudy but satisfying creature that had little to do with fact from the get-go. Though unprecedented and unnatural, his form still exists. It holds a wonky, mythic nature—which is the only nature a kid like me will ever understand.

The animal of my mind is bright and dandy and painfully incorrect. He’s living proof of my whacked-out desires and my ability to ignore cruel realties. And weirdly enough, he’s government-sanctioned; Lancelot follows the rules. The lines between our two lives are not so much parallel as bent—by sheer will, like spoons—until they touch.

Rather than a wild mustang or a trusty hound or even a Beatrix Potter bunny, my relationship with animals best resembles this cream-rinsed, mutant goat with a watery eye—this survivor of backwoods surgery with a pastel-bedazzled wang sprouting from his brain. The here and there of Lancelot grow together in my place, in the parts of my mind that—at the site of my beginning—were pulled back and rotated to sprout an outrageously new thing. There’s a distinct possibility that every time I write about an animal, I am only writing about him—which might also mean, horrifyingly, that I’m only writing about myself.

Yes, Lancelot says, and turns to me with his sparkling, goaty eyes. He looks right into my lonely soul and something in my cranium shakes. Come see what has been made for you—see the Living Unicorn. Come here, Elena Marie. Look into my eyes. Can you even believe all the ways you and I were made for each other?

From Animals Strike Curious Poses. Used with permission of Sarabande Books. Copyright © 2017 by Elena Passarello.

Listen: John Berger talks to Paul Holdengräber on President Trump, the emptiness of American political commentary, desire, place, and how the hell to keep going.