Winter has definitely arrived in New York, and it has me hunkered down with my mind on home and hearth. I’m not the only one, it seems. Like the pendulum swing of fad diets, many of those same people who just a couple of years ago were getting hygge with it, jovially stockpiling earthly delights in the soft glow of a thousand gently scented soy candles, are now frantically purging their homes of everything that doesn’t spark joy. Behind both these trends, of course, is the idea that home—for those lucky enough to have one—is a place that grounds, reflects, and defines. But what happens when this carefully ordered, self-contained universe begins to let in little bits of chaos? Little bits of what Freud called the Unheimlich, something familiar turned menacing by a slight shift of the frame. The houses in these four books are haunted, not by ghosts, but by the whisper of strange realities that are closer than we might like to think.

*

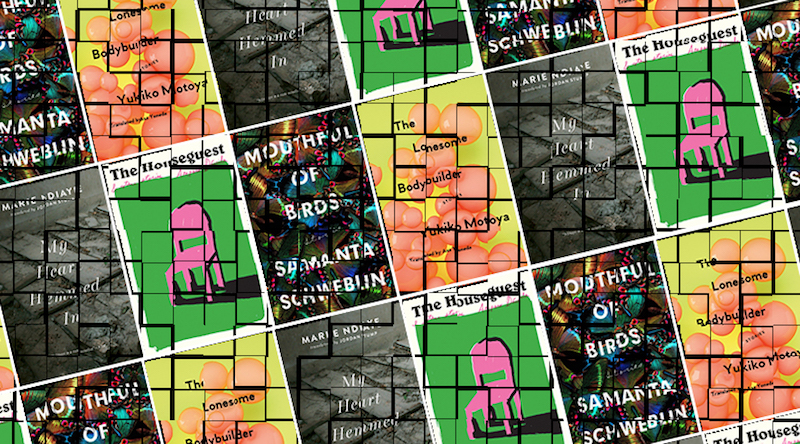

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin

Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell

Riverhead (January 2019)

I recently had the pleasure of talking with Samanta Schweblin about her latest translation into English, a collection of stories written in a similar key to her Man-Booker-finalist Fever Dream, particularly in the measure they take of the uncomfortable distance between what we want to know about the world around us, and what we suspect is actually there. The world of each of these stories has its own rules, and it’s not clear that the characters that inhabit it understand them any better than we readers do. Their despair in the face of this confusion can be disturbing, as with the women abandoned by their husbands along the side of the highway in “Headlights,” or the parents smashing through floorboards and walls at the slightest rustling after all the children in town go missing down a pit they’ve dug in “Underground.” It can also be darkly hilarious: in “Toward Happy Civilization,” a hapless traveler finds himself trapped indefinitely in a rural town because he doesn’t have exact change for train fare back to the city, and eventually gets wrapped up in a minor revolution, while in “The Heavy Suitcase of Benavides,” an overwrought but otherwise nondescript fellow shows up at his therapist’s home with his dead wife stuffed in a suitcase, which—much to his chagrin—quickly becomes the art installation of the century.

Double take: Lincoln Michel on these “stories full of weird” for BOMB, and a few more reviews, for good measure.

The Lonesome Bodybuilder by Yukiko Motoya

Translated from the Japanese by Asa Yoneda

Soft Skull Press (November 2018)

With the same easy swagger it must have taken to found a theater company to showcase her own work, in The Lonesome Bodybuilder Yukiko Motoya walks us confidently through a series of familiar worlds turned on their heads. Sometimes, as in the title story, this distortion is rooted in a personal transformation taken to its outrageous extreme: a neglected wife discovers a passion for taut, well-oiled muscles and begins a clandestine training program at her local gym, swelling right under her oblivious spouse’s nose; another woman, as she notices her facial features morphing gradually into those of her husband, devises an ingenious strategy for reclaiming her former profile. Sometimes the distortion is fantastic, like the discovery in “Typhoon” that—given the right psychological and meteorological conditions—umbrellas can launch a person into flight. And then, sometimes, there’s not really a way to describe what’s going on, as happens in “Fitting Room,” which finds a dutiful attendant in a designer boutique caught in an eighteen-hour marathon to find the perfect outfit for a client who… probably isn’t from around there. (Trouble keeping up? The good folks at Soft Skull provide, with tongue planted firmly in cheek, a list of “Seemingly Ordinary But Actually Magical Things in this Book.”) Though The Lonesome Bodybuilder is more whimsical than the other books on this list, the distortions that characterize its domestic spaces point in just the same way to the all-too-familiar inner contortions of isolation, longing, and fear.

Double take: Alexandra Kleeman recommends the collection over at Electric Literature, where (bonus!) you can also read the title story. Aaaand, here’s the roundup.

My Heart Hemmed In by Marie NDiaye

Translated from the French by Jordan Stump

Two Lines Press (July 2017)

After emerging breathless from my last reading of Marie NDiaye’s Self-Portrait in Green, I looked over at the sheer bulk of My Heart Hemmed In and thought there was no way she could sustain such intensity for nearly 300 pages. But somehow she does. The novel’s paranoiac beating heart is the desperate attempt of Nadia, a middle-aged, middle-class schoolteacher, to figure out why she and her middle-aged, middle-class schoolteacher husband have suddenly become social pariahs from whom children run screaming. Why they are spat on in the street and refused service in shops. And who it was that left a gaping hole in her husband’s abdomen with “some tool I don’t dare imagine, something both broad and sharp.” Even when she’s not stifled by the smell of decay slowly filling the apartment she once “kept up so lovingly and with such care,” Nadia is caught in a claustrophobic fog of diffuse but implacable hatred that follows her wherever she goes, a hatred that is all the more powerful for never being named. Perhaps the greatest mystery of all, though, is how NDiaye is able to sustain plot and tension along this filigree of silence, and how her characters manage to seem so three-dimensional, despite being sketched in the dark.

Double take: Victoria Baena on the defamiliarization of familiar worlds in NDiaye’s novels over at Bookforum. And here’s a rare treat: NDiaye’s virtuosic translator, Jordan Stump, on this stunning novel about “betrayal heartlessness, and incomprehensible meanness” that has, nonetheless, a “sort of happy ending.”

The Houseguest by Amparo Dávila

Translated from the Spanish by Audrey Harris and Matthew Gleeson

New Directions (November 2018)

On the heels of several decades in relative obscurity, Amparo Dávila is getting some of the recognition she deserves for her rich, unsettling stories, which have sparked comparisons to Shirley Jackson, Leonora Carrington, and Edgar Allan Poe. In 2015, she was awarded the Medalla de Bellas Artes and a short story prize was established in her name; more recently, her work reached readers of English in a collection titled The Houseguest. These stories, some of which date back to the 1950s, are littered with dysfunctional families, unhappy couples, and menacing… well, houseguests. There is the pair of unidentifiable (and apparently feral) pets that the narrator of “Moses and Gaspar” inherits from a suddenly expired sibling, which go on to destroy his apartment, run his lover off, and infuriate his neighbors. Or the raging young man who holds his entire family hostage from his cell in the basement of their suburban home. Or the woman almost driven mad by the discovery that her husband is having an affair with a… toad? In the guise of a femme fatale? Though fantastic twists do occasionally drive the plot, much of the horror in Dávila’s fiction takes place in that most intimate of spaces, the human psyche. According to Darren Huang, “Dávila embodies the shapeless terrors of the mind in bedrooms, basements and kitchen corners.” (Fun fact: the author makes a cameo in Cristina Rivera Garza’s extraordinary novel The Iliac Crest as an emblem of the innumerable women writers who have been pushed to the margins of literary history.)

Double take: Juan Vidal for the Los Angeles Times. And here’s a whole slew more.