Welcome to the Book Marks Questionnaire, where we ask authors questions about the books that have shaped them.

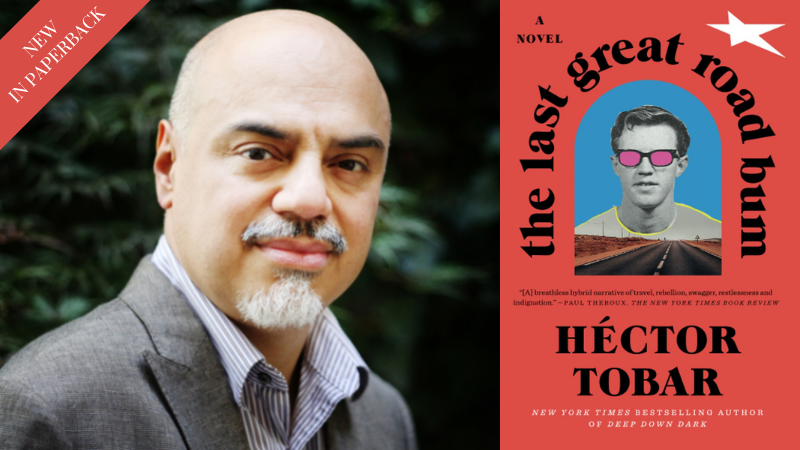

This week, we spoke to the author of The Barbarian Nurseries and The Last Great Road Bum (out now in paperback), Héctor Tobar.

*

Book Marks: First book you remember loving?

Héctor Tobar: Richard Wright’s Native Son. I had a terrible high-school education at an underfunded public school in Southern California. But I’m pretty sure that even “good” schools back then didn’t assign books that challenged American racism the way Wright’s 1940 novel did. When I got to college, one of my professors mentioned a novel written “by an African-American Communist”; not long afterward I was entering the basement of our college-town bookstore to buy a used copy of Wright’s masterpiece. It was the first book I’d read by an author of color, and I was blown away by how angry and fast-moving and violent it was. Today, I go back to the work and it feels raw and hurried, as if Wright had penned it from a prison cell.

BM: What book do you think your books are most in conversation with?

HT: My novel The Last Great Road Bum takes up the basic plot of Kerouac’s On the Road, but in a colonialist setting, with the protagonist wandering through the violent conflicts of the Cold War and the Pax Americana. My novel The Barbarian Nurseries is a Bonfire of the Vanities written from the perspective of a Mexican immigrant woman; it’s a study of the emotional and cultural scars inflicted by inequality, and a description of the insane social and ethnic divisions of my hometown, Los Angeles.

BM: A book that blew your mind? Favorite book of the 21st century?

HT: 2666. Roberto Bolaño’s magnum opus unfolds in a huge landscape of Mexican desert cities, Russian steppes, European apartments, and academic conferences. It’s a love-story to the craft of publishing and to the cult of the author; and it’s an odyssey into the bloodiest horrors to be found at the cusp of the twenty-first century, a series of crimes against women that every human being should know about. There are stories within stories within stories, an incredible feat that bibliophile Bolaño finished just before he died.

BM: Last book you read?

HT: In the most recent of the several cross-country road trips I took across the United States during the pandemic, I listened to an excellent audiobook performance of James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain. What a searing work. So lyrical and textured. It’s a story about family, and about one young man’s struggle to liberate himself from the strictures of an excessively devout family, and from the prison of Jim Crow. Baldwin wrote it in his twenties, and it carries the anger and the urgency of a work written by a young man desperate to be free.

BM: What book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

HT: Carribean Fragoza’s Eat the Mouth that Feeds You. This is a great, great debut collection of short stories from Fragoza, who hails from South El Monte, one of the many working-class Latino suburbs of Greater Los Angeles. Her stories unfold, for the most part, in mysterious landscapes inhabited by Latino people longing for connectedness and meaning. The book is filled with one moment of strangeness and transcendence after another.

BM: What’s one book you wish you had read during your teenage years?

HT: Hamlet. Like I said, I went to a terrible public school. Maybe we read a few scenes from Hamlet; if so, I don’t remember. But I wish I’d had that great high-school English teacher who opened the Bard’s dark masterpiece to me—and with it, the wonders of literature. Maybe I would have started writing novels sooner that I did. (I was a thirty-year-old newspaper reporter when I first decided to tackle fiction.) And certainly my first books would have been deeper, richer works. As it was, I read Hamlet (and saw it performed several times) for the first time in my forties; everything I’ve written since has been influenced by it.

BM: Favorite book to give as a gift?

HT: Edith Grossman’s wonderful, 2003 translation of Don Quixote. I’ve handed out this book as a gift at least half a dozen times. Grossman was the translator of many of Gabriel García Márquez’s novels into English, and she brings a deft, lively touch to Cervantes’s masterpiece. When I read it, I realized just how much realism there is in Don Quixote, and how much it’s a commentary on the meanness of everyday Spanish life, and its great social and ethnic diversity.

BM: Classic book on your To Be Read pile?

HT: All three of my children have read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. I have not. They tell me it’s pretty good.

BM: Favorite book no one has heard of? A book that actually made you laugh out loud?

HT: I’ve read a lot of great books by living writers whose works have reached a small audience. But I think it would be a grievous insult to them to have the label “no one has heard of” attached to their books. So I’m going to choose one by a dead writer who I think few Americans have ever heard of: Jorge Ibargüengoitia’s 1964 novel Los relámpagos de agosto. (I read it in Spanish, but it’s been translated into English, as The Lightning of August.) This book was recommended to me thirty years ago by the owner of a bookstore in Santa Fe, New Mexico that has long since gone out of business; I remain indebted to him, because the voice of the novel’s protagonist (a vain Mexican general) has never left me. Los relámpagos de agostois a laugh-out-loud parody of the narratives of the Mexican revolution, with its coups and uprisings and random craziness involving peasant armies, explosives, and railroad locomotives.

BM: Book(s) you’re reading right now?

HT: Mysteries, by the Norwegian novelist Knut Hamsun. This exceedingly strange and compelling novel was written by the 1920 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. The protagonist of Mysteries is stranger who deliberately shakes up the peace and order of a Norwegian village when arrives there. Hamsun later became a pariah in his own country, for his pro-Nazi statements during the German occupation of Norway in World War II. A friend recommended it; she and I will have an interesting conversation, I’m sure, after I finish it.

BM: Favorite children’s book?

HT: I read all thirteen volumes of A Series of Unfortunate Events to my kids when they were in elementary school. “Lemony Snicket,” the pen name of the author Daniel Handler, is a wizard of word play and social satire. Every page is a joy, and my kids would often laugh out loud when I read it to them, a few pages every morning before school for three years. We lost ourselves in the misadventures of the Baudelaire siblings, Count Olaf, and a menagerie of supporting characters with crazy names like “Dr. Georgina Orwell,” and “The Man with a Beard but No Hair,” and his partner, “The Woman with Hair but No Beard.”

*

Héctor Tobar is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and novelist. He is the author of the critically acclaimed, New York Times bestseller, Deep Down Dark, as well as The Barbarian Nurseries, Translation Nation, The Tattooed Soldier, and The Last Great Road Bum. Héctor is also a contributing writer for the New York Times opinion pages and an associate professor at the University of California, Irvine. He’s written for The New Yorker, The Los Angeles Times and other publications. His short fiction has appeared in Best American Short Stories, L.A. Noir, Zyzzyva, and Slate. The son of Guatemalan immigrants, he is a native of Los Angeles, where he lives with his family

Héctor Tobar’s The Last Great Road Bum is out now in paperback from Picador USA

*

· Previous entries in this series ·