Welcome to Secrets of the Book Critics, in which books journalists from around the US and beyond share their thoughts on beloved classics, overlooked recent gems, misconceptions about the industry, and the changing nature of literary criticism in the age of social media. Each week we’ll spotlight a critic, bringing you behind the curtain of publications both national and regional, large and small.

This week we spoke to writer, teacher, and book critic Heather Scott Partington.

*

Book Marks: What classic book would you love to have reviewed when it was first published?

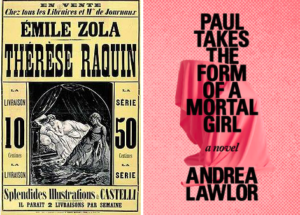

Heather Scott Partington: If something’s a classic, it already has a reputation, and one of the things I like best about being a critic is reviewing without any expectation. That said, I would want to review Émile Zola’s 1867 novel, Thérèse Raquin. It’s a twisted, carnal story of an affair, especially its aftermath—Zola makes us dwell in the appalling eventuality of Thérèse and Laurent’s romance and feverish plotting. The lovers pave the way for their own marriage while simultaneously corrupting it. So many 19th century romances build to a happy ending, but Zola’s is a deliciously macabre study of consequences. I’d love to review it now, frankly. Something about making your bed and having to lie in it seems apt for 2018.

BM: What unheralded book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

HSP: Andrea Lawlor’s magical-realist, gender- and shape-shifting novel, Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl, from Rescue Press. Lawlor writes of Paul/Polly, who is able to change genders and bodies at will. Lawlor’s writing as Paul/Polly moves through various circles of academia, 1990s queer culture, and the Bay Area pushes boundaries of sex and gender, but it does more than that. It poses important questions about intimacy and the extent to which the corporeal form allows human connection.

BM: What is the greatest misconception about book critics and criticism?

HSP: That there is one concept of “good” when it comes to books. We are a consumer society. People want to Google a rating: is it three stars or zero? Two thumbs up or none? I hate that kind of thing. Books are not lawnmowers. My stars might mean something entirely different than your stars, by the way. But a review is—or should be—its own piece of art. A review, written well, should guide you to a book if you’re the right person for it, even if there are negatives mentioned. The author’s plot, the author’s style, the critic’s thoughts and personal taste: all of these things should be speaking to the reader of a good piece of criticism so she can sift through them and decide for herself if the book is right at that moment in her life. I frequently read wonderful reviews of books that I know I will hate. I also read negative reviews that make me want to buy books. I wish sometimes we weren’t so myopic about how we discuss these things.

BM: How has book criticism changed in the age of social media?

HSP: I published my first book review in September of 2013. Two months later, the literary world was on fire about whether or not anyone was ever going to publish a negative book review again, and I was terrified about what that meant for my ability to be truthful as a critic. From time to time I’ll still see critics post online about whether or not it’s still okay to write a negative review, or that they feel guilty when they do so. I decided in 2013 that if my opinions were to mean anything, I had to render them all honestly. That includes the negative ones. I think that “No Haters” 2013 discussion is manifested in 2018 in the never-ending hype-machine on book Twitter. Sometimes I have to step away. It feels separate from the job I have to do when I sit down with a book, which is just to render, on the page, the experience of one person reading, and as Updike said: to try to understand what the author wished to do. If I start to think of my job as anything other than that, it feels insurmountable.

BM: What critic working today do you most enjoy reading?

HSP: When I was getting my MFA, I happened upon British critic and translator Tim Parks’ series for The New York Review of Books Blog. I didn’t know enough yet to know what I was looking at, but Parks’ deep dives into questions about why we read and how we read are the kind of criticism that draws me in. A little old-fashioned. Primarily divorced from anything buzzworthy. Filled with bird-walks, personal detail, and repeated references to the novels that shape us. Maybe a little cranky. There was something in his work about authority—something that as a new critic I needed to read just as I was looking to find my own voice. I didn’t always agree with Parks; that’s not the point, by a long shot. But I could see him thinking on the page. I wrote him a fan letter—it went unanswered. But that wasn’t the point, either.

*

Heather Scott Partington is a writer, teacher, and book critic. She is the winner of an emerging critic fellowship from the National Book Critics Circle. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, Newsday, The Star Tribune, Ploughshares, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. Heather is a contributor to Goodreads, Las Vegas Weekly, Electric Literature, and Kirkus. She teaches high school English and lives in Elk Grove, California, with her husband and two kids. @HeatherScottP

*

· Previous entries in this series ·