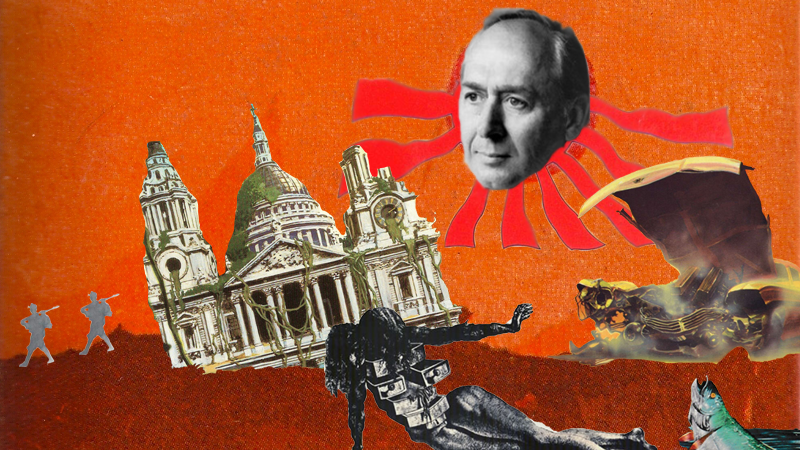

J. G. Ballard—the provocative English novelist, short story writer, essayist, and central figure of the New Wave of science fiction—died twelve years ago today.

Ballard left behind a diverse body of work that includes what we would now call a “Cli-Fi” novel (The Drowned World), a dystopian vision of Thatcherite greed and excess (High-Rise), an American censor-baiting political satire in stories (The Atrocity Exhibition), a nightmarish tale of car-crash sexual fetishism which one publisher returned to Ballard’s agent with the note “This author is beyond psychiatric help. Do Not Publish!” (Crash), and a good old fashioned autobiographical war yarn (Empire of the Sun), among many, many other strange and wonderful books.

Ballard wasn’t for everyone, but there can be no denying that he possessed a terrifyingly compelling vision of the world, one which struck a chord with legions of readers and influenced a generation of speculative fiction writers.

Below, we take a look back at some classic reviews—penned by Kingsley Amis, Zadie Smith, Paul Theroux, among others—of (arguably, of course) his five most iconic novels.

*

The Drowned World (1962)

The brief span of an individual life is misleading. Each one of us is as old as the entire biological kingdom, and our bloodstreams are tributaries of the great sea of its total memory

“In J.G. Ballard’s new book we have something without precedent in this country, a novel by a science-fiction author that can be judged by the highest standards. To my knowledge this level has yet been attained by only two American writers, Algis Budrys and Walter M. Miller. Mr. Ballard may well turn out to be the most imaginative of H.G. Wells’ successors, although he has expressly repudiated Wells as an influence.

The setting is among the super-tropical swamps, lagoons and jungles that, as a result of the increase in the sun’s heat, now cover most of Earth’s surface. Plant and animal life is reverting to the giant bamboos and reptiles of the Triassic Age. Among the members of a survey team, sent south from Greenland to determine whether parts of Europe may someday be reclaimable, a parallel but far more complex and disturbing regression can be glimpsed.

Those so affected share a recurrent dream in which they appear to be reversing the process of their birth, losing their identity in a warm sea that is at once the uterine fluid and the primeval ocean from which life emerged. In their waking hours they withdraw more and more irrevocably into the consciousness of their remote biological past, and the book ends with the hero’s departure on a lone trek southward toward some kind of paradisal graveyard of the species.

There is plenty of drama, notably after the arrival of a diabolical free-booter, bone-white in a world of darkened skins, whose ship is crammed with salvaged alter-pieces and equestrian statues and whose entourage consists of a band of half-civilized negroes and a pack of quarter-tamed alligators. By his agency the main lagoon is drained and a Walpurgisnacht enacted among the slime-coated buildings of what proves to be Leicester Square. But the main action is in the deeper reaches of the mind, the main merit the extraordinary imaginative power with which whatever inhabits these reaches is externalized in concrete form. The book blazes with images, striking in themselves and yet continuously meaningful.

There are perhaps faults of luxuriance, not very reprehensible anyway in a young writer. The similes, though often marvelously appropriate, sometimes crowd too thickly, and the author sees fit here and there to tell us that such-and-such is strange while amply demonstrating its strangeness. But he triumphantly achieves his object, set out in a fascinating article of his in a recent New Worlds Science Fiction, of exploring ‘inner space.’ His emblem is the metaphorical diving-suit, as against the literal space-suit of most of his contemporaries.”

–Kingsley Amis, The Observer, January 27, 1963

*

The Atrocity Exhibition (1970)

Deep assignments run through all our lives; there are no coincidences.

“…William Burrough’s remark in his preface to J.G. Ballard’s new novel, ‘An auto crash can be more sexually stimulating than a pornographic picture’…And Mr. Ballard weaves a cold-blooded fantasy of aberrant proportions around this idea. The fantasists are a doctor and his patient—or perhaps patients, since the names change even if the nightmares are fairly constant in their hideousness. His Doctor Nathan observes that ‘the car crash may be perceived unconsciously as a fertilizing rather than destructive event—a liberation of sexual energy,’ and he goes on to describe the sexual element in the deaths of James Dean, Jayne Mansfield, Albert Camus and John F. Kennedy. Indeed, the central idea of this novel is of man as a piece of meat somehow animated by a crack-up.

But this is more than the pornography of auto accidents; in another place ‘the mysterious eroticism of the multi-story car park’ is mentioned, and the erogenous zones of cars are exhibited. Elsewhere (‘it’s an interesting question’) sexual possibilities are proposed, the idea of making love with a rear exhaust assembly or ‘this ashtray, say, or . . . the angle between two walls.’ Mr. Ballard does not stop there; he does not stop at all. His hero, Travis (sometimes called Talbot, Trabert, Travers, and Tallis) is having a nervous breakdown—a crack-up of his own, you might say—and in the interrelated sections of the book he drools over the arousal potential of Kennedy’s assassination, the napalming of peasants, the atrocity movie, science in general (‘the ultimate pornography’), radiation burns on one’s intended, and finally observations on ‘the latent sexual character’ of the Vietnam war, which lead him to conclude with the deranged imagining that this war, for Americans, is a form of love.

It is a kind of toying with horror, a stylish anatomy of outrage, and full of specious arguments, phony statistics, a disgusted fascination with movie stars and the sexual conceits of American brand names and paraphernalia, jostled by a narrative that shoves the reader aside and shambles forward on leaden sentences strung out with words like ‘conceptual’ and ‘googoplex’ and ‘quasars’ and ‘blastospheres,’ one sees his craft (not to mention his Krafft) ebbing, and one is tempted to ridicule or dismiss it. It is a horrible book, and it is even in parts a boring and pointless book … Although it is, shall we say, unpersuasive as a whole, the details have an undeniable ring of pathological truth. Some people do find pain or human corpses sexually stimulating, or consider their cars as surrogate mistresses and see vulvas in handbags or car grilles, or enjoy atrocity movies and the current issue of sex magazines, and God knows, some sad man may at this minute be contemplating congress with a winsome ashtray or yearning amorously to disembowel a villager.

…

“Man is more than warm meat, but Mr. Ballard’s attitude is calculated. He says love when he means sex, and sex when he means torture, and there is nothing so fragile as sorrow or joy in the book. Some men may have an undeniable genius for cruelty and may applaud the parody of pain, the symbolically-wrecked stripper … if Mr. Ballard was an American he might have found it more difficult to misrepresent a war which, far from arousing us sexually, has made us impervious to suffering. It is not his choice of subject, but his celebration of it, that is monstrous.”

–Paul Theroux, The New York Times, October 29, 1972

*

Crash (1973)

I wanted to rub the human race in its own vomit, and force it to look in the mirror.

“Crash is, hands-down, the most repulsive book I’ve yet to come across. Sports Illustrated coverage of the Round-Robin eliminations at Ravensbruck would be somewhat less freakish…J.G. Ballard choreographs a crazed, morbid roundelay of dismemberment and sexual perversion. Crash is well written; credit given where due. But I could not, in conscience, recommend it. Indeed I most cordially advise against. Believe me, no one needs this sort of protracted and gratuitous anguish: except perhaps those who think quadruple amputees are chic.

…

“Punched out eyeballs. Blood. Vomit. Fecal matter. Decapitation. Sperm. Bifurcated, mashed genitals. Yet no one screams out pain. Injuries carry the reflective sweetness of a post-coital cigarette. And mannikins test-crashed can arouse with comparable efficiency. Violent events are stylized as radiator grills, ‘Conceptualized acts, abstracted from all feeling, carrying any ideas or emotions with which we cared to freight them.’ The functional automotive vocabulary has been restricted to no more than 20 terms. Instrument binnacle, steering wheel boss, windshield pillar—these recur with lunatic doggedness. J.G. Ballard intends to create a rite in metal, effacing humanness. The liturgy exasperates when, by reiteration, it no longer sickens.

Perhaps J.G. Ballard was traumatized at a drive-in theater. One would like to be sympathetic: the man has talent. But a partial list of his previous titles doesn’t reassure: The Disaster Area, The Terminal Beach, The Atrocity Exhibition. Though it is dangerous to infer creator from character, even when—as in Crash—they have the same name, I don’t think I’d care to meet J.G. Ballard. I certainly won’t read further in the Ballard oeuvre.”

–The New York Times, September 23, 1973

“It’s almost as if the stalker-sadist Vaughan looks at humans as walking talking examples of that Wittgensteinian proposal: ‘Don’t ask for the meaning; ask for the use.’ When Ballard called Crash the first ‘pornographic novel about technology’, he referred not only to a certain kind of content but to pornography as an organising principle, perhaps the purest example of humans ‘asking for the use.’ In Crash, though, the distinction between humans and things has become too small to be meaningful. In effect things are using things. (And a crazed stalker like Vaughan becomes the model for a new kind of narrative perspective.)

Now, I don’t think it can be seriously denied that some of the deadening narrative traits of pornography can be found here: flatness, repetition, circularity. ‘Blood, semen and engine coolant’ converge on several pages, and the sexual episodes repeat like trauma. But surely this flatness is deliberate; it is with the banality of our psychopathology that Ballard is concerned:

The same calm but curious gaze, as if she were still undecided how to make use of me, was fixed on my face shortly afterwards as I stopped the car on a deserted service road among the reservoirs to the west of the airport.

That seems to me a quintessential Ballardian sentence, depicting a denatured landscape in which people don’t so much communicate as exchange mass-produced gestures. (Reservoirs are to Ballard what clouds were to Wordsworth.) Of course, it was not this lack of human interiority that created the furious moral panic around this book (and later David Cronenberg’s film). That was more about the whole idea of penetrating the wound of a disabled lady. I was in college when the Daily Mail went to war with the movie, and found myself unpleasantly aligned with the censors, my own faux-feminism existing in a Venn diagram with their righteous indignation. We were both wrong: Crash is not about humiliating the disabled or debasing women, and in fact the Mail‘s campaign is a chilling lesson in how a superficial manipulation of liberal identity politics can be used to silence a genuinely protesting voice, one that is trying to speak for us all. No one doubts that the abled use the disabled, or that men use women. But Crash is an existential book about how everybody uses everything. How everything uses everybody.

…

“In Ballard’s work there is always this mix of futuristic dread and excitement, a sweet spot where dystopia and utopia converge. For we cannot say we haven’t got precisely what we dreamed of, what we always wanted, so badly. The dreams have arrived, all of them: instantaneous, global communication, virtual immersion, biotechnology. These were the dreams. And calm and curious, pointing out every new convergence, Ballard reminds us that dreams are often perverse.”

–Zadie Smith, The Guardian, July 4, 2014

*

High Rise (1977)

Let the psychotics take over. They alone understood what was happening.

“In High Rise, J.G. Ballard as in his previous novels, Crash and Concrete Island, focuses on two favorite fictional themes: technology gone awry, and human regression and savagery. In this instance, the result is less than satisfying.

The luxury apartment building east of London into which 2,000 middle-class and upper-class tenants have moved appears at first to be simply another tribute to architectural banality and conspicuous technological consumption. ‘An invisible army of thermostats and humidity sensors, computerized elevator route switches and overriders’ service the dwellers, providing ‘a more sophisticated and abstract version of the master-servant relationship.’ But soon enough the relationship is reversed: The building begins to assume an ominous power of its own; both the tenants and their idyllic, tinseled haven begin to deteriorate.

Dr. Robert Laing, who occupies a modest studio apartment on the 25th floor and narrates most of the tale, first notices the decay when a champagne bottle crashes onto his balcony. After this, the situation rapidly worsens. There are petty arguments among the tenants; the sophisticated gadgetry begins to break down; during an electrical failure, an Afghan belonging to one of the top-floor tenants is drowned in a swimming pool; a jeweler plunges to his death from the 40th floor; arguments escalate and soon turn into skirmishes and physical assaults. The high rise is swiftly transformed into a chaotic, primitive and insular world of armed tenant-clans—marauders perversely stalking one another, ‘free to pursue any deviant or wayward impulses.’

J.G. Ballard has constructed a parabolic tale (vaguely reminiscent of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies), in which the characters, apparently driven by the consuming sterility of their mechanized Shangri-La, revert to their most primitive qualities. But unlike the situation in the Golding book—where setting and characterization make the transformation credible—the escalating debauchery and violence in High Rise seem gratuitous. There is absolutely no indication of why the tenants remain throughout this ‘slow psychological avalanche that was carrying them all down’; yet no one leaves the high rise. And Mr. Ballard’s prose is riddled with intrusive psychological and sociological ‘insights’ meant to suggest the similarity between the high rise and modern technological society.

High Rise is a tale without a mooring; it occupies a kind of halfway house between science fiction and allegory that lacks the best qualities of both. It exploits both technology and human emotion in a compulsively vulgar manner. In short, High Rise the novel, like the luxury apartment building that is its setting, is a classic example of a fine idea wrecked by its own excesses.”

–Mel Watkins, The New York Times, May 11, 1977

“Set in a self-contained, tightly hierarchical tower block in England, the timeless story isn’t so much a warning about the future as an autopsy of the eternal now: As the building’s pampered residents begin to degenerate, without real provocation or awareness, into a state of being both feral and sublime, Ballard takes a detour around morality and presents this teeming, tribal anarchy as an inevitable reaction by the collective conscious against contemporary life. After passing through the depths of experimentation with The Atrocity Exhibition and Crash, Ballard used High-Rise to synthesize avant-garde science fiction with the sharp, clinical realism for which he would become known, a style partially a side effect, Ballard himself said, of the aborted medical studies of his youth. A cautionary tale minus the caution, High-Rise thrusts readers into an incest-ridden, cannibalistic labyrinth of the psyche that most never picture outside their own nightmares.

In spite of such grotesque abandon, the clarity and concision of High-Rise are remarkable. What often gets lost in the rush to paint Ballard as some highbrow shock-monger is the brilliance and rigor of his prose; wielding inventive similes, lucid depravity, and surgically crisp dialogue, he turns High-Rise from a mad stampede of orgiastic chaos into a measured, even stately parade of terror. His detractors dismiss his detachment as dryness, but Ballard’s deadpan, hermetic voice keeps the overall tone far removed from histrionic social commentary. It’s also the ideal counterpoint to his metaphysical, phantasmagorical, and frequently savage flights of derangement. In High-Rise, all these vectors converge in ringing, horrific harmony.”

–Jason Heller, The AV Club, February 18, 2010

*

Empire of the Sun (1984)

Jim knew that he was awake and asleep at the same time, dreaming of the war and yet dreamed of by the war.

“The first-rate science-fiction author, J. G. Ballard, has reached into the events of his own childhood to create a searing and frightening tale of wartime China. Indeed, Mr. Ballard declares in a foreword that this novel is based on his experiences in the Lunghua Civilian Assembly Center near Shanghai from 1942 to 1945. He has performed a heroic feat of memory to recover feelings that must have been tormenting to live through and can have been no less painful to relive in fiction.

Yet this novel is much more than the gritty story of a child’s miraculous survival in the grimly familiar setting of World War II’s concentration camps. There is no nostalgia for a good war here, no sentimentality for the human spirit at extremes. Mr. Ballard is more ambitious than romance usually allows. He aims to render a vision of the apocalypse, and succeeds so well that it can hurt to dwell upon his images. For Mr. Ballard seems to be against all armies and the ideologies that mobilize troops; he seems also to believe that the horror of his youth ended only when World War III began with a nuclear sunburst over Nagasaki.

…

“In complete control of his awesome material, Mr. Ballard is able to evoke the panorama of the apocalypse and then to plunge Jim and the reader into a genuine nightmare. Here is the stench of the dead stacked like wood, the brackish taste of river water polluted by corpses floating nearby, the strange singsong of peasants crying in frustration because they know they are about to be beaten to death. And here are scenes that are not believable except that they feel entirely real. Jim sees teen-age Kamikaze pilots crawl into their shabby planes without any more ceremony than the bored farewell of three other teen-age soldiers. He watches shallow graves deteriorate, exposing corpses that tempt the starving remnant as meat. And in August 1945, after a death march to the Olympic Stadium outside Shanghai, with the guards and the prisoners alike envying the sleep of the dead, Jim watches what he recognizes as the birth of a new empire of the sun that usurps Japan’s setting star. In the sky to the northeast of Shanghai, he sees a flash that momentarily overwhelms the dawn and floods the stadium with an odd light. Five hundred miles across the China Sea, Nagasaki has just been annihilated by the atomic bomb.

It would be comforting to say that Jim’s story closes happily when he once again embraces his parents by their drained swimming pool. He has survived the war by luck, and he has survived the end of the Japanese because canisters of Spam and powdered milk were dropped by the same kind of American airplane that dropped the bomb. However, Jim is not persuaded that the war is really over. He is equally uncertain what kind of world awaits him as he sails from China. The most optimistic thing one can say is that Mr. Ballard, with a splendid and powerful talent, has written a novel that makes haunting fictional sense of what happened to Jim 40 years ago. And with the wisdom born of having actually witnessed the potential of Armageddon, Mr. Ballard has now passed on the opinion that his own survival, and the world’s, remain tentative.”

–John Calvin Batchelor, The New York Times, November 11, 1984