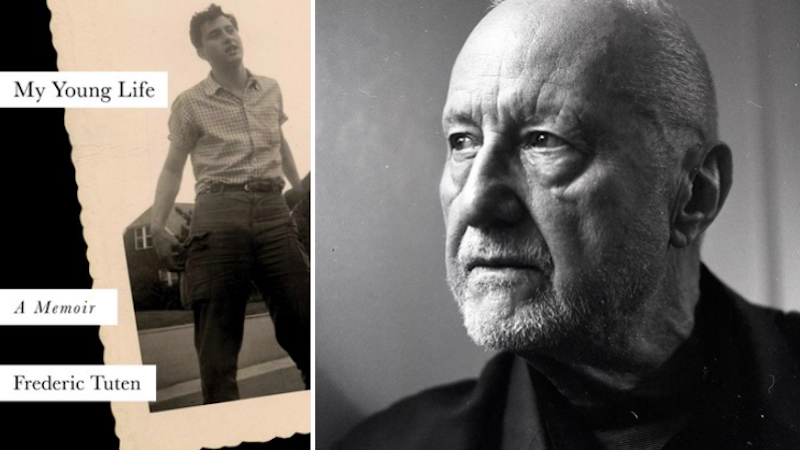

Frederic Tuten’s memoir My Young Life publishes next week. He shares five extraordinary memoirs.

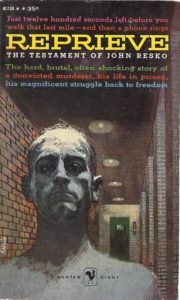

Reprieve by John Resko

This is the story of John Resko’s twenty years in Dannemora, one of the worst prisons in America, known as the Alcatraz of the North. At the height of the Great Depression, Resko was married at seventeen and had a child. He had no food or money, so he shot a man in a grocery store hold-up. He was caught and sentenced to death. His third and final reprieve didn’t come until forty minutes before his scheduled execution by electric chair. He became an artist in prison and was eventually released to pursue his life and career.

Resko was my artistic and literary mentor and a much-needed father figure during my teenage years in the Bronx. He plays a significant role in my memoir My Young Life.

Jane Ciabattari: What lessons did you learn from Resko when it came to writing your own memoir?

Frederic Tuten: I met John Resko in 1952, when I was about sixteen and had just dropped out of Columbus High School in the Bronx. I had wanted to be an artist—a painter. An older woman in my building, another of my mentors, fearing that I was too isolated and, in fact, perhaps going off the tracks and on my way to becoming a juvenile delinquent, introduced me to Resko. She thought that he, who had both been in prison for twenty years and was a painter, might guide and help me. He did, and my memoir details how.

Reprieve came out in 1956 and it hit me in a few ways. I had not known anyone who had written a book—no one in my family had even finished high school—and John’s very act of writing the book was a powerful beacon to me. He wrote every morning and shut the world off until he felt he was done for the day. As for the writing itself, it was strong and unsentimental and went to the truth of his life in prison. The memoir told me—as had his life—that in the worst conditions anyone can make his or her way. But to do that you needed will and patience and belief and the ability to endure: how else could John not only survive the hourly brutality of prison life, but flower in it, teaching himself to write and to paint well enough that eventually he attracted the outside attention of important people. These people were so drawn to his work that they spent years trying to get him paroled. Could I not, then, even on a humbler scale, by my own hard work, one day leave the Bronx and the poverty and smallness of the life I was expected to live?

An aspect of John’s memoir has stayed with me, and gave me the hope that I could follow in his footsteps. It was Resko’s wish for the mot juste, his insistence that every word be exact and not its second cousin. And that that perfect word was perfectly placed. I once asked John why, in describing the exterior of Dannemora prison, he said, “architectonically speaking” and not “architecturally speaking.” I didn’t understand the difference and perhaps I still don’t. But what impressed me was his diligence and his wish for exactitude. I’m amazed that I remember his using that phrase after all these 65 years.

Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict by Peggy Guggenheim

Before reading this memoir, I always thought of Peggy Guggenheim as a kind of stodgy person whose celebrity came from being rich and from patronizing famous artists, by building a museum in Venice. I always pictured her as an older, imperious woman, as she seemed in that famous photograph of her in Venice, flanked by two tiny dogs. That is to say, I always imagined her as someone who had never experienced life but only dabbled in it. When you’re young, you never can imagine that an older person has had such an intense romantic life, for instance. In fact, she was an astonishing and fascinating woman, as this memoir shows. I was also extremely smitten by her bursts of wisdom.

JC: To this day I think of visits to her museum in Venice, and the choices she made when selecting the work for her collection. What were the biggest surprises for you as you read her stories about her life?

FT: There are plenty of people who have lots of money and spend it foolishly or selfishly without any purpose except amassing more riches. What made me adore Peggy Guggenheim was that she used her wealth to live to the hilt and that in the process did a great deal of good, if you believe that art has a place in the good. I love her dedication to pleasure. Before reading this memoir, I had no idea of her love affairs, her marriages, her flirtations. She lived among artists whose work she loved and who, in several cases, she supported and brought to light. That apart, she had a kind of sense of reality that I admired.

For example, among her ridiculous marriages—mostly to men who wanted her money—was one husband who spent her fortune lavishly, but who caviled with the billing account of her live-in chef while they were living in the south of France. Her husband claimed the chef had been cheating them, pretending to buy more than what was needed for their meals and getting money for the difference. Peggy’s husband wanted her to fire the chef for it. Mind you, this was during the time of year when much of the touristical south of France was shut down for off-season. Peggy was not pleased with the few restaurants that had remained open, so she imported one of the most famous chefs in Paris to live in her villa and cook. She told her husband she had no wish to fire the chef because the amount he was allegedly stealing from them was of little importance compared to the need for his services.

Of course, I admire her wisdom here. As much as her wisdom for collecting art and making a beautiful little museum in Venice that the world could visit. I must not forget that she paid the rent for a writer I greatly admire, Djuna Barnes. Although, she complained that Barnes had never thanked her.

Living my Life: Volumes 1 & 2 by Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman inspired me through the strength of her anarchist convictions and by the strength of her commitment to social change, a commitment that came at a great cost to her. Her books are windows into a radical time in America that is sadly forgotten. She is relevant as an example of what integrity and spirit means in the darkest political and social climate. During my own radical youth, her life was a testament to living what one believes.

JC: What most impressed you about the ways in which Goldman acted upon her political beliefs?

FT: First of all, her beliefs were radical even in a time when radicalism was current. She was in the avant-garde of everything that even matters today: worker’s rights; birth control; sexual freedom for women, which meant freedom to have sex without having to be constrained by marriage; sexual acceptance of gay men and lesbians who faced prejudice and persecution; freedom of speech; freedom of press. And she lived her beliefs and took the consequences of them. When she spoke against the draft during the First World War, she was convicted under some statute and spent two years in prison. She thought the act of saying what she had said, in speaking out against the draft, was worth the two years in prison.

But I’m extremely impressed that when she was in the Soviet Union, she saw very quickly the political repressions of everyone outside the Bolshevik sphere. She spoke against the suppression of workers’ rights and of anarchist and other non-Bolshevik radicals. Most especially, she was against the power of the state itself, whether it was capitalist or communist, or whatever name it called itself. She was brave enough to share her feelings about the revolution with Lenin and it was clear in his response that she’d better quit town soon, and she did. She is my hero.

Here’s a funny item: Peggy Guggenheim gave the anarchist Emma Goldman $4,000 and a place to live so that Goldman could write her autobiography.

A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway was my idol as a youth. I loved his short stories especially. I was also enamored with what seemed to be his rich, exciting life. I loved his memoir not only for his portraits of writers like Gertrude Stein and F. Scott Fitzgerald, but also for the glamor he enrobed Paris with. The memoir’s prose is as seductive as his portrait of the city. Hemingway fed my youthful fantasy of what it meant to be an artist and what it was to be a writer in Paris.

JC: My darling Mark, who you know, and I read this to each other aloud, chapter by chapter, as we were falling in love as undergrads at Stanford (well, we were engaged after knowing each other two weeks, so we read pretty fast!) When we read of Hemingway living in a circle that included Braque and Picasso, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, writers and artists transforming culture, it became a model as we began our life together, long before we first visited Paris. How did A Moveable Feast influence your life?

FT: As mentioned, I had already been powerfully influenced by Hemingway before A Moveable Feast, as many in my generation were. I used to joke that no one could write a grocery list without being influenced by Hemingway’s prose. But it was not just the prose, it was the glamour of his life, for me. As a Bronx boy, the idea of his having lived in Paris and traveled widely had great allure. I myself, at the age of 15, had been galvanized by the thought of Paris and what I imagined to be the artistic and literary scene there. So Hemingway’s myth had already sunk in. But then, A Moveable Feast besotted me completely. I imagined Paris as still being the way he had described it, and I dreamed of being in the very streets and cafés and brasseries he had wrote about in the book. It took a while for me to finally go to Paris and eventually live there. The very first time I was there, I asked a friend to take me to La Closerie des Lilas because I wanted to see the place that Hemingway lovingly described in The Sun Also Rises

After that, everything in Paris seemed the way Hemingway had described it. Every street, every café seemed the way he described it in the memoir.

Even though Paris has so radically changed since the years Hemingway and I had been there, for me, Paris is still his Paris. It is a place that appears in my novels as if it were my home, my true home.

The Price of Illusion by Joan Juliet Buck

I had wanted to read this book because I’d known Joan slightly over the years and had been to her fabulous dinner parties in New York before she left to become the editor of Paris Vogue. What started for me as a mild curiosity ended as a complete admiration for Joan’s daring and passionate life. She writes about some of the more fabulous characters of our time: Peter O’Toole, Tom Wolfe, and her own extraordinary father and mother. It’s a compelling, extraordinary book.

JC: I’m thinking of the section where Joan is eleven and she and her parents move to Ireland to stay with her godfather, John Houston, and she becomes friends with Anjelica, and later, when she was running Paris Vogue, featuring Madame Claude, who invented the term “call girl.” There are so many extraordinary moments, told with such clarity, and matter-of-factness. How do you think she achieves this effect? And what did it show you about telling your own story?

FT: Joan’s book came out just as my own had been accepted for publication. So, in short, I had not read it before working on my own memoir. My relationship to it is not a matter of influence but a matter of affinity. I, myself, had filtered in and out of the Conde Nast and Vogue world when I was writing film reviews in the 60’s. Many of those experiences paralleled with Joan’s, although at different times. It was wonderful for me to see her perspective on the very celebrities I had brushed shoulders with or who were my friends, like Alexander Liberman, for example, the Editorial Director of Vogue.

Joan’s world was filled with glamour and elegance, both sartorial and personal. But most of all, I felt touched by Joan’s childhood and by her parents, who were models of perfection and illusion. Their rise and fall is of tragic proportion. That is to say, from luxury and indulgence and grand villas to the south of France to penury and claustrophobic apartments somewhere in Los Angeles. I love this book.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·