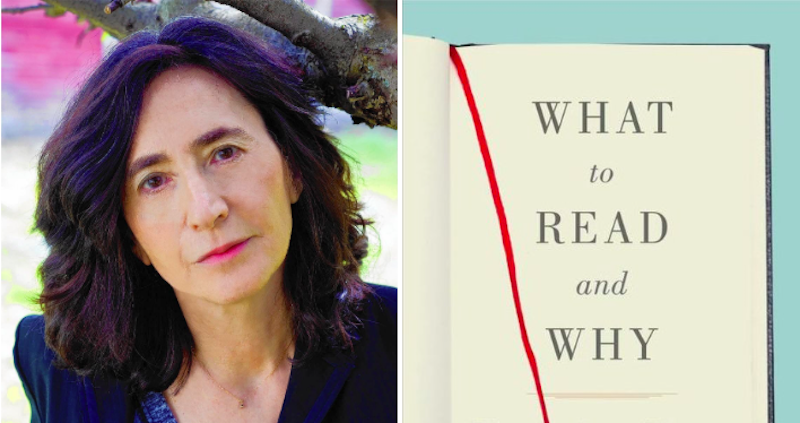

Francine Prose’s new book, What to Read and Why, is published this month. She shared her list of classics to read and re-read with Jane Ciabattari. (And she had to leave off Anna Karenina!)

*

George Eliot, Middlemarch

Every time I read it I understand something (or sympathize with someone) I didn’t understand (or sympathize with) before. Maybe that’s why Virginia Woolf called it “one of the few English novels for grownup people.”

Jane Ciabattari: The admirers of Middlemarch include Virginia Woolf, as you note, Emily Dickinson, V.S. Pritchett, Julian Barnes, Martin Amis, Rebecca Mead. A few years back, Middlemarch came out first in a poll I conducted for BBC Culture of the 100 greatest British novels as voted by critics from the rest of the world. Eliot seems both Victorian and modern, with a sense of point of view that quietly undermines the realism of the novel. She also was a genius at creating full-blown characters. Which of the imperfect creatures in Middlemarch seems to you most morally complex?

Francine Prose: It’s a contest, because all the major characters are morally complex, except perhaps Casaubon, whom our heroine Dorothea marries; Casaubon is such a pompous stiff, who cares about his complexities? Dorothea makes us see the vanity in wanting to be a good person, and Dr. Lydgate must balance what he wants with what his wife wants; he must choose between career and social advancement and doing the right thing. I’m talking about these characters as if they were real people, which is part of the pleasure of Middlemarch. We get to experience life in a dreary genteel backwater, at a moment when women weren’t allowed or expected to do much—and we don’t have to actually live there.

The Complete Stories of Anton Chekhov

No one had greater compassion; no one has given us a fuller or deeper or broader sense of what it means to be a human being.

JC: Or a dog. I’m thinking of “Kashtanka,” in the story by the same name, the mongrel who gets lost, becomes a circus performer, and is restored in the end to a less pleasant but more familiar master. Which stories continue to resonate with you, and why?

FP: In a way it doesn’t matter which Chekhov story you read, and my favorites keep changing, so many are truly great. I’m teaching “The Lady with the Lap Dog” and “The Witch” in the fall, at Bard. I don’t know if they’re my favorites, but I’m hoping that the class can talk about how literature can change our way of thinking, if only about a character: a person. That mental porousness and fluidity seems more welcome than ever these days, when our judgments and positions about our fellow humans seem not only to have hardened, but turned to stone.

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

Because it’s (to me) the most morally complex Dickens novel, the one in which it’s hardest to distinguish the heroes from the villains, it’s remained my favorite.

JC: It is an indelible story. Do you think Pip’s first-person narrative enhances its complexity? If not, what is it?

FP: The thing about the novel I keep coming back to is that it was written to be published in serial form and save Dickens’s magazine, which was about to go under. You could say it was meant for a time like ours, when—if we are honest—it’s a challenge for a book to keep us away from our phone. It’s meant to make you want to know what happens next, and a big part of that is Pip’s voice. The gorgeous, inventive, witty and rhythmic sentences get hold of you in chapter one and don’t let go. Eloquent, funny, charming, laceratingly observant of the adults around him, curious, brave, and soon convinced that he is entitled to something better, Pip narrates one cliffhanger chapter after another. The pace, the intensity and the beauty of the language never slacken as the novel goes deeper and deeper.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time

The book I’d take to the desert island, because by the time you get to the end, it’s time to go back to the beginning and see what you’ve missed. Plus Proust gives you a rich social life, useful if it’s just you, the sane, the water, and that palm tree.

JC: Jennifer Egan once told me she and her Brooklyn reading group began In Search of Lost Time the week of 9/11 and finished it seven years later. It was a big influence on her novel A Visit from the Goon Squad. Has Proust influenced your own fiction? And your sense of time?

FP: Proust’s novel is like some great cathedral or symphony, you hear and see it differently every time, even if you just hear a phrase, see a photo of the basilica, read a section at random. It’s jam-packed, you can find everything there, the metaphysics of time and space, treatises on love and art, an active social life at a moment when you don’t yourself have one. Now that I am a grandmother, I plan (I mean right now, as soon as I finish writing this) to reread “the grandmother” sections in the novel. Appropriately for a book about time, the novel has different moments for different…moments. If you’re having a jealous love affair, it’s all about Swann and Odette, the narrator and Albertine. There’s a scene near the end in which the narrator goes to a party and thinks everyone he used to know is wearing the mask of age. I’ve been to that party several times in the last few years.

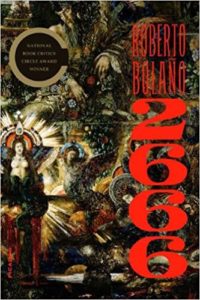

Roberto Bolano, 2666

A detective story, an academic novel, a tribute to the dead women of Juarez, poetry on every page, what else could you want?

JC: I remember when 2666 won the 2008 National Book Critics Circle award in fiction, the translator, Natasha Wimmer, said that Bolano once told her “posthumous” sounded like a Roman gladiator. Wimmer also compares 2666 to Moby-Dick, a point you make in What to Read and Why, that a similar “encyclopedic impulse” prevails in each—in Bolano’s case, a listing of all the names and crimes and circumstances of the murdered women of Ciudad Juarez (or Santa Teresa in he novel). You also write that reading 2666 makes you feel “some powerful force has moved through the writer…” What is that force? Outrage? An articulation of evil?

FP: What’s the force that moves through Bolano? Outrage? The articulation of evil? All those things, but mostly poetry and storytelling. The stories are moving through him, and on every page there is some section you want to read aloud even if you are alone or (worse) on the subway. In the book I talk about my favorite section, a wild monologue by a seer and healer named Florita who appears on local TV and goes into a trance and says the thing—the one important thing—that everyone knows but no one’s been able (or wanted) to say for hundreds of pages.