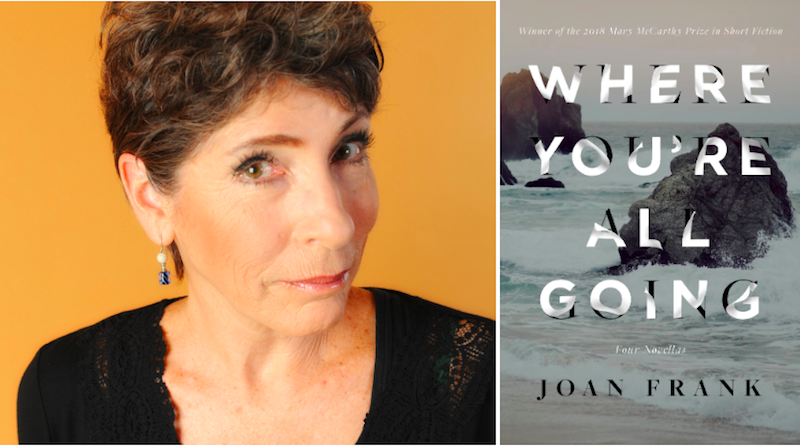

Joan Frank’s Where You’re All Going, winner of Sarabande’s Mary McCathy Prize, is published this month. She shares five short novels that continue to shine, noting, “I love short novels: love the clean, finite, stretched, framed canvas of them; love their troublesome neither-nor-ness. For me as a writer, the choice of that form’s never foregone: the story dictates its length, scope, and narrative distance as it unfolds. This may sound bizarre, but I have worshiped plenty of titles—been formed by them, sworn by their importance—yet no longer clearly remember their particulars, nor care to. The phenomenon’s something like what Maya Angelou once said about certain people: you never forget the feeling they gave. Here are a handful of short novels that continue to pulse for me—like lighthouses whose brilliance flashes rhythmically through the skull.”

So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell

So Long, See You Tomorrow struck me full-force, as a developing writer who’d (like Maxwell) lost a mother while still a child. The empathic range and fierce honesty of this work, the tenderness and laser-accurate vision, the distilled concision of its language, shot into my heart to stay—to inform everything that ever happened to me, or that I ever thought or wrote or said, thereafter. I cannot urge this title too strongly on anyone who may still wonder why literature matters.

Jane Ciabattari: Like his narrator, Maxwell lost his mother to the 1918 flu epidemic. It’s only as he becomes older that he understands his interactions with Cletus, a boyhood friend. “The one possibility of my making some connection with him seems to lie not in the present but in the past,” Maxwell writes. To what extent do you think his narrator’s perspective affects the power of this work?

Joan Frank: I think the use of first person in So Long accomplishes what Paul Auster once described to me, and mentioned above: a reader feels she is being spoken to from the bones of her own skull; an intimate reverberation—as if she is almost co-thinking with the narrator. And in piecing together the past, the trauma of that original big bang which effectively formed and infused him forever after, Maxwell is able to summon an overview of human weakness, error, courage, pain—at the same time, expressing a unilateral tenderness, and forgiveness, for all of it. May I here recommend the slender, stunning A William Maxwell Portrait: Memories and Appreciations, an anthology of remembrances edited by Charlie Baxter, Ed Hirsch, and Michael Collier. The contributors are all-stars (Paula Fox, Shirley Hazzard, Alice Munro, John Updike, etc.) and almost every piece there is luminous, but readers will want to zero in on the fierce, brilliant discussion of So Long by the incomparable Ellen Bryant Voigt. You’ll be electrified, and want to reread and reread this amazing volume.

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin

Giovanni’s Room, read when I was still a young girl, blew my head off. Its rich sensuality, its pith and dimension, the music and surge of his language, made me begin to grasp that writing can go where others haven’t yet dared. It alerted me to a first inkling of complex, erotic life—but also of a human longing which transcends eroticism.

JC: Baldwin’s first sentence is exemplary: “I stand at the window of this great house in the south of France as night falls, the night which is leading me to the most terrible morning of my life.” What are your favorite moments?

JF: This book is so full of extraordinary language, of wisdom so preternatural for a young author (he was thirty-two), almost every page arrives as a quiet explosion, delivering revelation after wrought revelation. “Nothing is more unbearable, once one has it, than freedom.” “People are too various to be treated so lightly. I am too various to be trusted.” Of the protagonist’s boyhood embattlement about his father: “I was beginning to judge him. And the very harshness of this judgment, which broke my heart, revealed, though I could not have said it then, how much I had loved him, how that love, along with my innocence, was dying.” And of poor Giovanni’s room itself: “I remember that life in that room seemed to be occurring beneath the sea. Time flowed past indifferently above us; hours and days had no meaning.” The book is excruciating, a solvent. You move in wonder through its sentences, their glittering insights, as you might through the Sistine Chapel. I hadn’t read it since I was a teenager, yet I soon found the moment that had once electrocuted me: “But I’m a man,” I cried, “a man! What do you think can happen between us?” “You know very well,” said Giovanni slowly, “what can happen between us. It is for that reason you are leaving me.”

Train Dreams by Denis Johnson

Train Dreams sat me down hard. It arrives exactly as a dream might, uttered in a single breath, from a fugue state, seeming to carve a slice of American history and push it forward into collective consciousness—yet always intact inside its dense, dream-ambience.

JC: Louise Erdrich has called Train Dreams a “stirring surreal incantation.” I read it aloud to my Montana-born husband as we drove through Wyoming a few years back, and we both were caught up in a strange dream about Robert Grainier, an orphan, who grows up in the Idaho woods, marries, works in logging camps, loses his wife and baby to a wildfire (we both know about wildfires) and so on. Train Dreams is woven into the memory of that road trip. Sentence by sentence, it’s astonishing. Johnson knows the West, and the woods. “The wolves and coyotes howled without letup all night,” he writes, “sounding in the hundreds, more than Grainier had ever heard, and maybe other creatures too, owls, eagles—what, exactly, he couldn’t guess—surely every single animal with a voice along the peaks and ridges looking down on the Moyea River, as if nothing could ease any of God’s beasts. Grainier didn’t dare to sleep, feeling it all to be some sort of vast pronouncement, maybe the alarms of the end of the world.” How would you explain his ability to range so widely in such a condensed fashion? Is it this intimate third person point of view?

JF: What a beautiful passage you chose—yet this brief book is so saturated with them, one longs to quote from almost every page. Re-reading it, I find it even more astonishing than remembered: a kind of hymn to the harsh beauty of a life lived (and partly dreamed) simply and artlessly (artless in the Jamesian sense, as a purity of sensibility and consciousness) earlier in the last century. Yes: Johnson’s deploying a very close third person POV. But it’s most intensely tone that triumphs here: an omniscient, authoritative, sometimes near-stentorian folktale-teller’s tone, rendering incidents and memories into yarns, myth, fable, like stories told around a campfire. And yes, you’ve correctly discerned Johnson’s skill in tacking far backward and forward in time, rendering as if immediate any number of anecdotes and memories (Native American Kootenai Bob, who ends his life drunk on railroad tracks, or a gentleman whose dog has allegedly shot him) and then reminding us, by turns, that the whole trajectory of Grainier’s life is simultaneously being mulled, weighed, measured: seen in sepia, finally. “Years later, many decades later, in fact, in 1962 or 1963, [as] he watched young ironworkers on a trestle where U.S. Highway 2 crossed the Moyea River’s deepest gorge…it occurred to him that he’d lived almost eighty years and had seen the world turn and turn.” As a core sample of some of the very best writing, this small yet mighty testament to a period of American history, will stand and endure.

A Month in the Country by J. L. Carr

A Month in the Country infuses me like a gentle dye. Plainly yet shrewdly told, it’s the story of a veteran freshly scarred by the Great War, taking up temporary residence in the bell tower of a church whose ancient wall-mural he’s been asked to restore. It reads differently, as one ages. Some people disdain it. Too bad for them.

JC: There’s a point when Carr writes of Alice Keach coming to visit his narrator. She brings him apples—Ribston Pippins. And then: “I should have lifted an arm and taken her shoulder, turned her face and kissed her. It was that kind of day. It’s why she had come. Then everything would have been different. My life, hers.” His language is simple, yet devastating.

JF: Absolutely correct. As I say, this is a story that enters one differently as one ages (Vivan Gornick’s forthcoming Unfinished Business, about the essential need for re-reading, couldn’t be more timely.) When I was younger, the ache of my own longing for a straight-up romantic resolution between the narrator and Alice felt unbearable, as if I would burst into flame in my furious wish to will the event: “Kiss her! Kiss her, you fool!” Something, too, about the (exquisitely conveyed) seasons and natural beauty Carr portrays (so stark a counterpoint to the remembered horrors / ugliness of war) seems to surround the maddeningly tentative romantic leads like a wild river, both cossetting and rushing them, urging them to give in, unite at all levels—sexually, soulfully—almost as a running commentary: “Now, now! If not now, when?” Yet when one is older, and seen and lived our endlessly various and complex consequences, one sadly, deeply, bittersweetly understands the narrator’s heroic restraint, his instinct for refraining. And I still grieve it!

A Whole Life by Robert Seethaler

In A Whole Life readers meet Andreas Egger, a quiet man who spends most of his life in the Austrian Alps, in the early-to-mid twentieth century. Very much like the protagonist of Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams (and that of John Williams’ Stoner), Egger works very hard, asks for little, wonders at the power and beauty of nature and of men’s steady encroachment upon it, and endures crushing personal loss. Seethaler’s prose seems to fuse seamlessly with its painfully pure focus: the great, spinning world, and the arc of a simple man’s brief, yet meaningful, tenure there. If this book (and its above siblings Train Dreams and Stoner) had a soundtrack, it might be Aaron Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man. I cannot overstress how moving, how unforgettably beautiful, this simple, cumulative narrative proves itself to be.

JC: There is a subdued quality to Seethaler’s narrative, which functions much through observation, as in this paragraph, with its brief glimpse of his late wife:

The sun was low, and even the distant mountaintops stood out so clearly that it was as if someone had just finished painting them onto the sky. Right beside him a lone sycamore burned yellow; a little further off some cows were grazing, casting long, slim shadows that kept pace with them step for step across the meadow. A group of hikers was sitting beneath the canopy of a small calving shed. Egger could hear them talking and laughing amongst themselves, and their voices seemed to him both strange and agreeable. He thought of Marie’s voice and how much he had liked to listen to it. He tried to recall its melody and sound, but they eluded him. ‘If only I still had her voice, at least,’ he said to himself. Then he rolled slowly over to the next steel girder, climbed down and went in search of sandpaper.

What makes it seem so satisfying?

JF: The passage you cite is such a splendid example of how Seethaler crafts his astonishing story—yes, mainly through observation. Again and again one sees that God’s in the details. Seethaler’s camera follows Egger very closely, registering the experience of all the senses, color and light and shape, sound and smell, temperature and taste—at the same time, too, of thought and vocalized words, however simple—yet also panning back to let us take in the full, painfully beautiful tableau. And the reader’s stunned in a slow, cumulative, rapidly opening awareness, like a lens widening and widening, of the matchless, harsh, painful beauty of the earth, and our time here. A quality of inevitability, and of music, infuses the flow. “O isn’t life a terrible thing, thank God,” intones Dylan Thomas in Under Milk Wood. Books like these, for my money, are the supreme gift, the jewel in the heart of the lotus—dwelling in us for the duration.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·