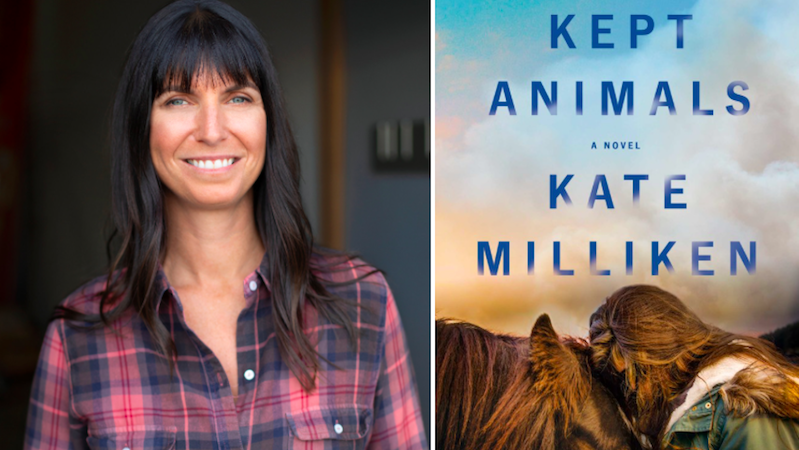

Kate Milliken’s Kept Animals is just published. She shares five novels born from the mother-child bond.

Amy and Isabelle by Elizabeth Strout

This novel dramatized, painfully well, the fraught emotional complexities of being a teenager and wanting to separate from your mother. It prompted me to mine that time in life for my own storytelling purposes.

Jane Ciabattari: Amy, the teenager, and Isabelle, her mother, yearn for connection but are driven apart by a ”confluence of different longings.” The choices Isabelle has made, ending in her working as a secretary in a mill in Shirley Falls, a small New England town, have shaped Amy’s life. For years, Amy has ”wanted a different mother,” more like “mothers in television ads.” How does Strout use this contrast to build their conflicts?

Kate Milliken: Obviously Amy wants what she can’t have, but she has what she does because Isabelle herself made so many sacrifices. And Strout moves flawlessly between both of their perspectives, granting each of them validity and building our intimacy, so the contrast of Amy’s desires against Isabelle’s resolve is deeply felt. Strout suggests early on that there is more to Isabelle’s story, that she is withholding things from Amy, to pique our interest. That secret, of course, which is about Amy’s paternity, creates an inevitable if unintended distance between Isabelle and her daughter. But because we are not yet let in on the secret either, we still sympathize with Amy and her frustration, so that when Amy—in perhaps both an unconscious response and an effort to define herself separately from Isabelle—starts a relationship with an older man, we understand, we don’t judge her! It’s so well done, leaving the reader twisting uncomfortably in empathy for each of them as they try to define themselves in ways that aren’t true to who they are or what they wanted for their lives. It’s such a wonderfully drawn story. All of Strout’s work, but especially this book, has taught me so much about how I want to live, but without being allegorical; she writes characters to whom you can’t help but attach, they are so real, and so their experiences, their journey, shift something in me on a cellular level.

The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina Henríquez

A gripping portrait of a mother, Alma, and the choices she and her husband make out of love for their young daughter, Maribel. I admired Henríquez’s rendering of the innocence of love and the way in which guilt is the real complicator in this mother and child relationship.

JC: Alma’s daughter Maribel, whose traumatic brain injury led the family to move from Mexico to Delaware for special schooling, is wooed by Mayor, whose family fled Noriega’s Panama. Alma’s attempts to protect Maribel are understandable, yet they lead to tragedy. Henríquez alternates her tale of two families to give us a chorus of narrators, including one who says, “We’re the unknown Americans, the ones no one even wants to know, because they’ve been told they’re supposed to be scared of us and because maybe if they did take the time to get to know us, they might realize that we’re not that bad, maybe even that we’re a lot like them.” How does this immigrant backdrop affect their mother-daughter bond?

KM: That quote says it all; it is the emotional beat of this novel’s heart, articulating the dark power fear has and how it gets wielded to divide us from one another. Of course, once in Delaware, Alma holds on tightly to Maribel because, as immigrants, they are living with the anxiety of constant scrutiny and Maribel is even more vulnerable because of her brain injury. From there, Henriquez masterfully reveals how Alma’s own fears, from the legitimate (deportation and the malevolent neighborhood teen) to the more imagined threat (the love of Mayor) are all exacerbated by her own guilt; her fear that she is responsible for her child having been hurt. It is so subtlety done, but Henriquez manages to show us that our fear of the other is most deeply rooted in our fear of what we do not know of ourselves.

Nothing to See Here by Kevin Wilson

With perfect levity this nontraditional mother and child story shows us how we sometimes need and get to choose our parents. Despite or maybe because of its oddity this is a story that I identified with as both a parent and as a child.

JC: Bessie and Roland, twins, are five when their politician father replaces their mother with a younger stepmother, and ten when their mother dies. The stepmother hires Lillian, an eccentric former classmate who is at loose ends, and sets her up with the twins in a flamboyantly decorated guest house on their father’s estate—which turns out to be a former slave quarters. The tricky part, which Wilson pushes to great effect, is that the twins burst into flames when angry. What makes those scenes effective at reflecting the rage sometimes felt by children toward their parents?

KM: It might be something of a cartoon trope to have a character who is angry burst into flames, eyeballs go fiery, or steam blow from his ears, but to witness it in the prose of Kevin Wilson is to actually feel the heat of the truth of this analogy. And while any parent can be insufferable at times, poor Bessie and Roland have been cursed with a negligent politician for a father—a situation about which any of us might feel some red-hot rage, no? They’ve been relegated, basically abandoned, in their own backyard! Since the frustration that Bessie and Roland feel is so within our comprehension, Wilson manages to make this fantastical occurrence read like perfectly commonplace literary realism. And it works doubly well because what parent hasn’t felt as helpless as Lillian when she first encounters these explosive twins. Find me a child who hasn’t exploded into flames! Bessie and Roland are just the perfect articulation of the molten hot center of us all.

Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion

Didion’s character Marie Wyeth is an iconic portrayal of a mother driven over the edge by her love for her daughter Kate and her regret about the child she did not have. Like none other, this narrative made me feel the immensity of love one feels for a child before I had known it for myself.

JC: “The only problem is Kate. I want Kate,” Maria notes at one point. Maria is in the midst of a breakdown, and thinking of her young daughter Kate, who has an “aberrant chemical in her brain,” is what keeps her from sinking into nothingness. Which passages best explain Maria’s connection to Kate?

KM: My first inclination here is to reference the white spaces that Didion used. That lingering between each curt chapter gives us a chance catch our breath, but it also lets us feel Maria’s yearning and the porousness of her mental state. For me, Maria doesn’t have a true connection to Kate, so much as a need of her, an emptiness that she wants Kate to fill. So it’s their disconnection that makes this book so devastating. There’s one particular passage I’ll highlight here that isn’t explicitly about Maria’s feelings for Kate, but that articulates her yearning for those she loves, or wanted to. She’s just been stood up by a casting agent—yet another disappointment—and the chapter ends like this: “‘I have to go now,’ Maria said, and without waiting for him to speak she turned and began walking toward the gate. Once in her car she drove as far as Romaine and then pulled over, put her head on the steering wheel and cried as she had not cried because she was humiliated and she cried for her mother and she cried for Kate and she cried because something had just come through to her, there in the sun on the Western street: she had deliberately not counted the months but she must have been counting them unawares, must have been keeping a relentless count somewhere, because this was the day, the day the baby would have been born.”

Shiner by Amy Jo Burns

A multigenerational novel that hinges on the secrets a mother was compelled to keep from her daughter, Wren, and how Wren is changed by learning the truth. Set in the Appalachian Mountains, I so admired the way this setting is mirrored in the way these characters related—or failed to relate—to one another.

JC: Wren is fifteen and isolated from the nearest town in West Virginia, living up the mountain with her mother and her snake-handling preacher father, who is marked from having survived a lightning strike. The only outsider she sees regularly is Ivy, her mother’s best friend, who visits daily. “Everything changed when Ivy caught fire,” she writes. Her mother’s soap pot had spilled hot lye and grease down the front of her. Her father does a healing. Her mother’s face says “Run. There’s danger here.” The rest of the novel unfolds from there. Burns describes moonshine country, the razorback mountains and ravines, the meadows the forests, the foxes, rusted trailers, sun-scorched toys, her father’s snake shed, their hidden cabin, in exquisite detail. How does the setting mirror their bond?

KM: The stories surrounding Wren and her mother, Ruby, are so fraught, so intertwined, overlapping and concealing just like the backroads through the mountain, the tree knotted skyline. Every character in this book has a myth about themselves that they’ve nurtured more than the truth, so it is left to Wren to pull back the brambles of it all and find the glinting object of truth beneath it all. Ruby is as almost allusive to Wren as her snake-charming father, but Wren clearly has more faith in her mother’s narrative about their family history, so it is through the Ruby’s letters to her daughter that we make our way through the woods—they are our crumbs on the path. Actually, there is one fragment of a letter, about three-quarters of the way through the novel, that articulates the weight and power all of stories of mothers and their children, and it is this: “Dear Wren, I have to tell you—The only legend that ever really mattered was ours.”

*

· Previous entries in this series ·