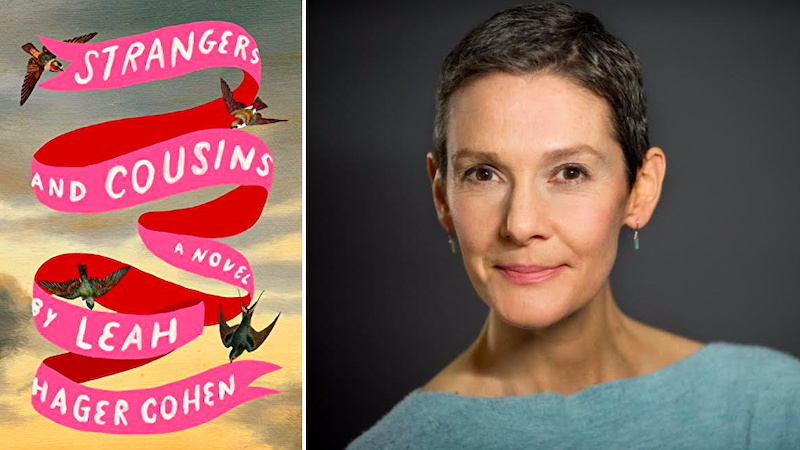

Leah Hager Cohen’s Strangers and Cousins is published this month. She shares five books about sprawling families.

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

The granddaddy of them all, the Buendía family of Macondo. How does he do it—balance such feats of eccentricity with some kind of underlying order that holds it all, improbably, in place?

Jane Ciabattari: Good question. How does he?

Leah Hager Cohen: Far be it from me! But if I were to hazard a guess, I wonder if it’s something to do with the nature of his sentences. While the story abounds with fantastical characters and occurrences, his syntax and diction are calm and firm, clear and direct. And then too I wonder if it’s his respect for limits. Father Nicanor levitates, yes, but only under certain conditions: when he drinks a cup of chocolate. Remedios the Beauty ascends to heaven, yes, but it’s not some random arm-flapping voyage: there’s an almost quotidian inevitability about the way she’s drawn skyward by the wind catching the bedsheets she has been folding in the garden.

His is a measured, proportionate extravagance. The quantity of out-and-out miraculous events that occur in the novel is relatively modest. The thought strikes me now (it may be slightly heretical) that, relative to the enormity of the world he perceives, we might actually call García Márquez a great minimalist.

Delta Wedding by Eudora Welty

The language, the languor of it, like water rippling along a lazy Mississippi creek…and then the variety of its characters, all gathering for a wedding, each of whom is looked at through a lens at once honestly critical and flooded with forgiveness.

JC: Welty made a point of choosing the year 1923 as a time when no historic event ruffled the landscape and disrupted the family; “nothing very terrible had happened in the Delta by way of floods or fires or wars which would have taken the men away.” This allows echoes of World War I and the Civil War to filter through her story, and the front-stage, back-stage preparations for the wedding to be examined. I wonder which characters you find most involved in forgiveness?

LHC: I hesitated before naming this book, because there’s a way in which I think the book itself requires forgiveness, or maybe it’s that I’m not sure I forgive myself for loving it. Welty’s depiction of the black characters is problematic. And the book—I think there’s really no angle from which this isn’t the case—makes an idyll of plantation life. But I think it’d be cowardly of me to leave it off the list as a way of avoiding discomfort.

And here is why I think it is worth talking about this book, and wrestling with my love for it—because every one of its many characters (black and white alike) is afforded such particularity, such complexity. And although the world of the book may be an idyll, none of the characters are idealized. Instead they are loved. Loved in the sense of seen in full, in beauty and grotesquerie, in virtue and flaw. They are wonderfully imperfect. They care for one another and hurt one another and fail one another, just as humans do.

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith

A poor, artistic family moves into a disastrously dilapidated castle. “Madcap” is the word that springs first to mind, yet it doesn’t do justice to how soulful this book can be, to the longing that pierces through its very British wit.

JC: To what extent do you think the narrative voice through Cassandra’s diary drives this novel?

LHC: Oh it’s all about her voice, isn’t it? From the opening, where we meet Cassandra contorting herself to perch on the drainboard with her feet in the kitchen sink so as to capitalize on the waning light in which to write, to the final lines of the book, where we are reminded that all this verbiage is being scribbled in a series of notebooks, each precious page getting thoroughly filled before turning to the next (“Only the margin left to write on now”), we have an awareness of her unquenchable need to make sense of the world around her by putting pencil to paper.

And no wonder. The world around her is in bad need of order. The Mortmains are living in a literally crumbling ancient castle, scraping by on mere shillings and oatcakes and candle-ends. Scarcity, hugely present in this novel, is counterbalanced by the opulence of Cassandra’s seventeen-year-old passions for poetry and love. In a way (a silly way but a very real way, too), her opulence on the page, even as she strives to keep it in check (“Oh, I long to blurt out the news in my first paragraph—but I won’t! This is a chance to teach myself the art of suspense”), does as much to patch up the holes in her home and her family as any more practical solutions. This may be why I love the book. Because who among us has never known the feeling of living with scarcity of one form or another, of living with precariousness and lack, and learning what innate resources we have to help hold the broken bits together?

Running in the Family by Michael Ondaatje

Technically not a novel, but I’m hoping to shoehorn this in—this fever-dream of a book that includes poems and photographs and gossip and tall tales that turn out to be (perhaps) true, about the author’s own wildly preposterous family in Sri Lanka.

JC: Ondaatje opens this hybrid book with a fascinating line: “What began it all was the bright bone of a dream I could hardly hold on to.” And he takes that line as permission to mix genres, including fictional sections, memoir, even poems, all in a flood of memory and reminiscence and exploration. This was published in 1983. Can you think of 21st century authors who took up his approach?

LHC: The first book that springs to mind if Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, with the section that appears as a PowerPoint presentation. And then Maria Semple’s Where’d You Go, Bernadette? with its lively scrapbook-style narration juxtaposing report cards, emails, invoices, FBI documents, a live-blog transcript of a TED Talk, etc. There’s some genre mashup going on in Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, and lots of David Foster Wallace—oh wait! I just thought of Leanne Shapton, who wrote the illustrated novel Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry, which she calls “a love story told through an auction catalogue.” So yes, if anything I suppose the 21st century might be even more conducive to experiments in jumbled-together forms than earlier eras.

But here’s the thing about Running in the Family. I never sense Ondaatje is setting out to be innovative. What I sense is his surrendering himself to become a vehicle for the way this unruly story needs to be told. And that it hangs by a thread to existing as a book at all—that it might as easily have found its final form as an eclectic variety show performed on the back lawn on a summer’s night by torch light.

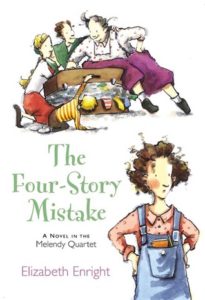

The Four-Story Mistake by Elizabeth Enright

This is a children’s book, and it still runs vibrantly through my veins. The Melendy family (four children, a dog, Father, Cuffy the housekeeper and Willy the handyman) relocate from New York City to the countryside, to a house so quirky it’s known as The Four-Story Mistake.

JC: This book harks back to the early 1940s, with illustrations by the author. What has kept it so memorable?

LHC: The sheer, vibrant messiness, I think. Not only is the house a ramshackle, funny-looking thing, there’s a wonderfully porous boundary between domesticity and wilderness. I’m thinking of the way the children are forever and very naturally extending the idea of “home space” beyond the walls of the house, like when they dam the brook to build a swimming hole, or Willy cooks himself breakfast outside, or Rush, the older boy, spends a night stranded in the treehouse during a raging storm. And then the opposite is also true: the children discover strange, uncharted realms within the house itself, as with the sealed-up room that belonged to Clarinda, or the dank, dirty basement that proves a glittery treasure trove.

Even though it’s “just” a children’s book, and a squarely old-fashioned one at that, it does something I think great literature does—something I am grateful to literature for doing—which is dislodge our fixed ideas of things. The sense of wondrous permeability that the Melendy children have—that the Melendy children live—remains important to me to this day.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·