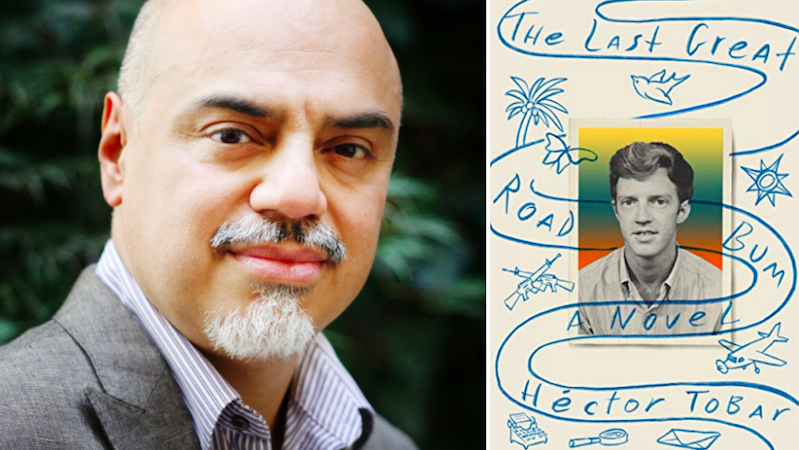

Héctor Tobar’s novel, The Last Great Road Bum, has just been published. He shares five iconic literary road trips.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

The original, great American road-trip novel. Mark Twain tackles slavery, the original sin of the United States of America, and also his own childhood memories of the Mississippi in this seminal work. It’s a crazy and very funny Odyssey through America, with an unlikely love story at its heart. Too bad Twain fudged the ending.

Jane Ciabattari: How do you think he fudged the ending?

Héctor Tobar: The arrival of Tom Sawyer and Tom’s Missouri relatives at the end of the novel felt completely contrived to me, and totally inorganic to the story, a real deus ex machina moment. My theory: Twain had reached the end of his word count and wanted to wrap things up, so he resorted to bringing in the popular character from the novel’s prequel.

2666 by Roberto Bolaño

Among other things, this book is built on a series of road trips to various locales of the dark, beautiful 20th century: a violent Mexican border town, assorted stops in literary Europe, a prewar German village, and to the Eastern Front of World War II in the Soviet Union, where a Wehrmacht soldier discovers the manuscript of a Russian sci-fi writer hidden in a Ukrainian hovel.

JC: I recall being at the awards ceremony when 2666 won the National Book Critics Circle fiction award posthumously. Board member Marcela Valdes, who presented the award to translator Natasha Wimmer, called the novel a “sexy, apocalyptic vision of history.” Which of the road trips you mention strikes you as the most apocalyptic vision of history? Which is most relevant today?

HT: The storyline that unfolds in “Santa Teresa,” a fictionalized version of the real-life Ciudad Juárez. The relentlessness of the descriptions of the infamous femicides in that border city are a horrific allegory for all the cruelties of the late twentieth century. We live in a time in which modernity seems to have conquered all—and yet human beings, and women especially, can still be subjected to the medieval torments Bolaño so vividly describes.

On the Road by Jack Kerouac

Truman Capote famously dismissed this work by saying, “That’s not writing, that’s typing.” True, Kerouac isn’t a stylist. But what a story he lived. I love On the Road for its documentary qualities, for Kerouac’s eye for the variety of characters to be found in America’s outsider subcultures. (But what a shame he had to hide the gay love story at its heart.)

JC: Kerouac’s Beat chronicle stretches from New York City to the American West, with stays in San Francisco and Mexico; its beating heart is his fascination for outsider characters: “…the only people for me are the mad ones,” Kerouac writes, “the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww?’” Which characters are your favorites?

HT: “Terry, the Mexican girl.” She’s a farm worker and single mother, who meets Sal Paradise (Kerouac’s fictional alter ego) on a bus in the San Joaquin Valley of California, headed to Los Angeles. She’s fierce, passionate, a recognizable Mexicana of her day. More than half a century later, the writer Tim Z. Hernandez tracked down the real “Terry”: Beatrice Kozera was her name. He interviewed Kozera and wrote a wonderful novel about her, and her short love affair with Kerouac. It’s called Mañana Means Heaven.

Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino

A fanciful journey along the Silk Road, with Marco Polo describing one magical city of the empire after another to the empire’s ruler, Kublai Khan; this is a work of prose-poetry that speaks to the power of language to convey the sense of wonder the road can bring us.

JC: Calvino’s passages for each of the 55 “invisible cities” evoke wonder. Take Theodora: “Recurrent invasions racked the city of Theodora in the centuries of its history; no sooner was one enemy routed than another gained strength and threatened the survival of the inhabitants. When the sky was cleared of condors, they had to face the propagation of serpents; the spiders’ extermination allowed the flies to multiply into a black swarm; the victory over the termites left the city at the mercy of the woodworms. One by one the species incompatible to the city had to succumb and were extinguished. By dint of ripping away scales and carapaces, tearing off elytra and feathers, the people gave Theodora the exclusive image of human city that still distinguishes it.” These are cities constructed of ideas. How does he make them seem so concrete?

HT: Calvino uses the oldest trick in the book, the same thing I teach my writing students: sensuous detail, and utterly unique turns of phrase that bring that detail to life. And he’s pulling off a wonderful sleight of hand too: as the narrator Polo reveals at the end, “Every time I describe a city I am saying something about Venice.”

Bolivian Diary by Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara

There’s nothing like a doomed road trip. This is the day-by-day account of Guevara’s journey to rural Bolivia, and his ill-fated attempt to start a revolution there. Idealism, betrayal, hubris: this story has it all. Guevara began in 1966 with a group of about 60 men and women, thinking he was about to start a continental uprising; but it all ended a year later, with just a handful of survivors, nearly all of whom were executed (as he was).

JC: To what extent were you inspired by Che’s Bolivian Diary while writing The Last Great Road Bum, which was inspired by the diaries and archives of Joe Sanderson, an Illinois-born American who died fighting in the Salvadoran revolution?

HT: When I first encountered Joe’s diary, in El Salvador, more than 20 years after he died, I thought I’d come across an American version of Che’s Bolivian Diary. I thought I’d write a book about a “blond Che” from Illinois. But the story ended up being so much deeper and more textured than that. Among other things, Joe had been to 70 other countries on his “road bumming” adventures before he even got to El Salvador. And there was a love story at the heart of Joe’s life too—the love he never lost for his family, and for his Midwestern hometown.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·