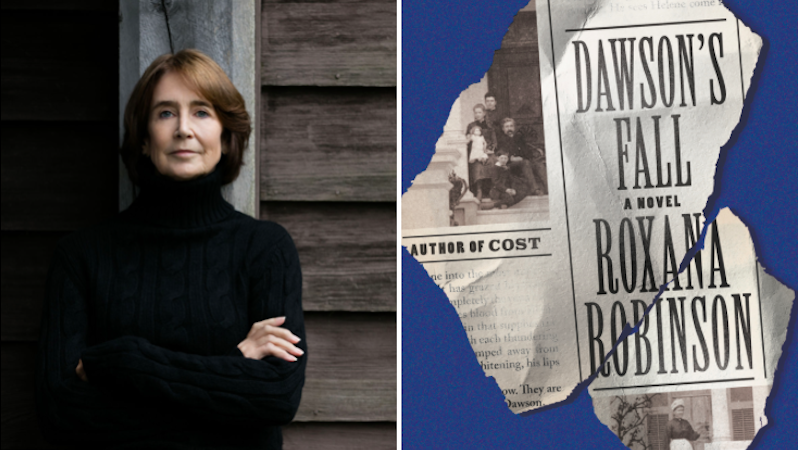

Roxana Robinson’s new biographical novel, Dawson’s Fall, is published this month. She discusses five historical novels that inspire her.

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

There is always one book that I use when I write, something I flip open every morning before I start, reading from any page. For Dawson’s Fall, this book was Wolf Hall, in which Mantel shows that the phrase “historical novel” needn’t mean stiff, romantic or stereotyped. What’s so wonderful about Mantel’s book is that it’s written in very modern language, so it feels very immediate and accessible, but it’s based on historically documented fact, so it also feels utterly true and trustworthy. Mantel is a powerful writer, so the narrative moves fast and inexorably, and she’s a realist, so the book contains the frightening darkness of a modern novel.

Jane Ciabattari: Wolf Hall, which won both the Booker and the National Book Critics Circle award, uses an intimate third-person narrative voice to tell Thomas Cromwell’s story, and dialogue that feels like its period and yet has a modern feel. How do you think she accomplishes that? And did you find her approach dialogue helpful while working on Dawson’s Fall?

Roxana Robinson: I met Mantel once, and asked her about the dialogue. She said she’d gone back in history, before Shakespeare, to find the rhythms of her characters’ speech. I don’t know what works she studied, but I pored over Mantel’s writing to see how she avoided the trap that awaits historical novelists – having people speak the way they write. You want to give a flavor of the period, but you don’t want the talk to sound stilted. In every period people have used dialogue for the quickest, subtlest, most oblique, urgent or telegraphic kinds of communication, as well as the more formal kinds. Jane Austen, and Trollope, for example, write very modern dialogue, which is often quick and easy and funny. I used all these writers as models, trying to show that people spoke a bit more formally, but they still had fun, made each other laugh, got mad, teased, spoke elliptically, tenderly and rudely – in fact they used words just the way we do. I was trying to avoid the risk of formality, which puts dialogue into a strait-jacket.

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante

Set in Naples nearly 70 years before its publication, this book reveals the true costs of crime to society. Rejecting the glamorous gloss that we’ve given to those charming rogues, goodfellas, Ferrante shows how the entire community, starting with the most helpless and vulnerable members—the children—are affected by the brutal and ruthless rule of the Camorra. She portrays this society so vividly and so powerfully that we can’t help but compare it to our own, and wonder how we allow such things to evolve.

JC: As Elena notes, she feels “no nostalgia for our childhood: it was full of violence.” My Brilliant Friend has drawn millions of readers, giving Ferrante a global influence. Perhaps this conflict between childhood innocence and crime is universal?

RR: I think we share a universal feeling of horror at the connection between children and crime. We know it’s fundamentally wrong; we know it exists. That’s one of the last frontiers, for a writer, children at risk of such violent harm. It’s written about rarely, the taboo is so strong against it. It’s a subject that can’t be discussed; even to admit that it exists is somehow damaging to society. Most writers who choose to write about crime don’t write about children, and vice versa. Ferrante addresses this dreadful conjunction, showing us how lethal violence to the community affects women and children: the bosses abuse the men below them, and the men pass on the violence to their families. It’s one of the most powerful portraits I’ve ever read of crime, and its real effects on society. Women love these books because they play an important role here, one that has been overlooked in the past. These books tell a truth about women and children that has gone untold.

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Written in the early 1920s, but set nearly fifty years earlier, in the 1870s, Wharton drew on her own childhood memories and her family history to create this rendering of Old New York. Though she was describing a society that had been lost, she had a deep and intimate knowledge of it and how it worked. She had acquired it in the way we learn things from our families—often tacitly, an understanding of what had been admired, what feared, what denied, what chosen.

JC: I recall taking part in a marathon reading of Wharton’s The House of Mirth you organized at the Center for Fiction a few years back, when you said, “Hers was a small, privileged world, in which family was more important than wealth. This world was tribal and insular, with a rigid caste system and a strict code of behavior. The code was Puritanical, driven by moral rectitude, self-reliance, and stoicism. Self-control was essential; emotional display was anathema. To grow up in that society—and many of us here today did—was to know the enormous social forces implicit in the command, “Don’t make a scene.” Newland Archer, his betrothed May Welland, and her cousin, “Poor Ellen Olenska,” are on the cusp of change in opening scene of The Age of Innocence, when he spots May Weiland with her mother at the opera house and then realizes they have included Olenska, whose presence is scandalizing his friends. That setpiece opening is remarkable. Do you think Wharton shows even at that point Newland Archer’s ambivalence, and his potential attraction for this woman who defied convention?

RR: I think every word Wharton sets down is deliberate. Hardly anyone is more skilled at creating exquisite designs: her novels are like Renaissance jewelry. Everything is set out in the opening scene at the opera, where she reveals the great, glittering mechanism of New York Society, formed by the struts of family, the wheels of fortune, the cogs of convention. Archer, the young man at the center, is supremely certain of himself, his position, his fiancee, his future. The tone of Wharton’s narrative voice in this description—worldly, sardonic and crystalline in its precision—informs us that Archer’s confidence will prove his undoing.

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

This was published in 1869, but written about the Napoleonic Wars of 1812—long before Tolstoy was born. But he takes masterful control of the place, the characters, the society, the dialogue, creating a world that had been handed down to him through his own knowledge of Russia, and through his family, but writing from the distance of another generation, one that watched these scenes from a new perspective. This is what I find fascinating—a writer who can sink into another world, embedding herself in it, while using a modern sensibility to understand it.

JC: Tolstoy also sinks deeply into each character. Do you think the multiple perspectives helps build these many worlds?

RR: Absolutely. One of the things that makes Tolstoy such a great writer is his ability to empathize with his characters, and the big sweep of War and Peace allows him an enormous range of possibilities. Tolstoy can imagine himself as anyone, it seems. In one scene he goes inside the mind of Russia’s arch-enemy, Napoleon. And Tolstoy makes him sympathetic: Napoleon is taking a moment alone in his tent, to look at the small portrait of his son which he carries with him, even to war. In Anna Karenina Tolstoy writes a wonderful passage from inside the mind of Levin’s favorite retriever, Laska, as she hunts birds in a swamp, with breathless excitement.

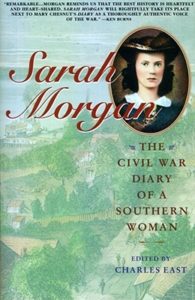

The Civil War Diaries of Sarah Morgan Dawson

These were written by my great-grandmother in Louisiana during the 1860s. In order to write my book it was essential to hear the voices of my family, to learn what made up their days, what they were reading, what troubled them and made them laugh. Almost everyone, it seems, in my family was a writer, so I could draw on Sarah’s memoir, as well as that of her husband, Francis Warrington Dawson, and her brother, James Morris Morgan. Reading their stories allowed me to tell them in my own way; it also reminded me that I’m part of the same braided history. I was fascinated to see how familiar were parts of Sarah’s character: her love of gardening, her love of reading, her impatience at pretentiousness. I could see how the family beliefs, attitudes and failings had been passed down through the generations, which is how we repeat ourselves, unwittingly, throughout the centuries.

JC: Dawson’s Fall includes passages headed “Sarah Morgan’s Diary.” How close are they to your great grandmother’s diary? You also include multiple newspaper accounts. Are they from actual clippings?

RR: Everything is real. Everything in a different font is a verbatim quote from the cited text. So the letters and diaries are written by Sarah and Frank. The newspaper stories are real. The congressional testimony is real. That’s why we’re calling it a biographical novel, because in some ways it’s a conventional biography, drawing on documents and research, but in some ways it’s a novel because I’ve made the shape of the narrative, and I’ve created the dialogue and the interior monologues. The big problem in a biography, which I faced in my book on Georgia O’Keeffe, is achieving authority over your subject’s thoughts and speech. You don’t want to say “She must have thought,” which puts you on the speculative side-lines, but you can rarely say with authority, “She thought,” unless she wrote it in her diary. You can never say, “She said,” because no-one knows exactly what is said in a conversation – people remember only the substance. You can’t make up dialogue. But calling this book a biographical novel allowed me to use the extensive archival material, and to use Frank and Sarah’s own words – they were both wonderful writers, perceptive and articulate. I didn’t want to lose their voices, which I’d have had to do if I were to write a conventional novel, using only my own voice. So it’s a hybrid form, a biographical novel. Neither conventional form was quite right for this story.