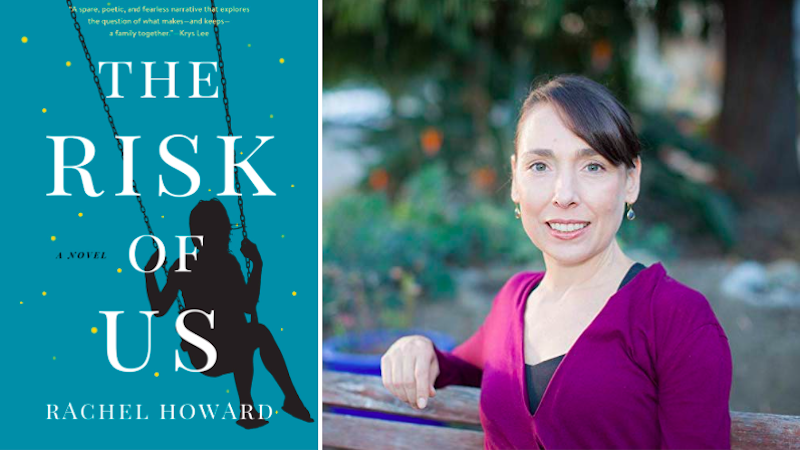

Rachel Howard’s The Risk of Us is published this month. She shares five great writer biographies.

Ross and Tom: Two American Tragedies by John Leggett

Somehow I discovered this book when I was 23 or 24; it had just been reissued, but from the price marked in pencil on the title page, it looks like I found it in a used bookstore. It’s a very peculiar double-biography: Ross (Lockridge) and Tom (Heggen) are notable for being now virtually unknown. Each was ordained a Jonathan Franzen of their era in the 1940s after the publication of a first novel; each went into crisis under the sudden pressure, became paranoid and creatively paralyzed, and ultimately committed suicide. I’m glad I read this book so early in my writing life. I think reading it as a warning can save a developing writer from cravings for “making it big”—cravings that miss the point of the work for its own sake. It also saved me from getting hung up on wanting to be “the next Jonathan Franzen.” Ross and Tom were the next Jonathan Franzens, and now their novels are remaindered. This book helped me decide that you can write without attachment to outcomes that are external to creating what you hope to create.

Jane Ciabattari: Ross and Tom is such a surprising book, a dual psychological portrait of two first-time authors, and a cautionary tale about literary success. How would first-time authors benefit from reading it?

Rachel Howard: I think it’s a cautionary tale about putting too much of your identity and self-worth in the idea of literary success, that’s how I think it’s helpful. It’s also a good reality check about the publishing industry, as in: these tastemakers who love books are just human beings with individual subjective reactions. Sometimes they choose a certain work to be the “it” book and put tremendous machinery in place to make that happen. This can be fairly arbitrary, or driven by cultural trends and mainstream aesthetics that are passing, not eternal. So you’ve got to separate the machinery (or lack of benefitting from the machinery) from the work itself.

Flaubert and Madame Bovary, A Double Portrait by Francis Steegmuller

I found this biography when I was finishing my MFA program, at age 32. A friend was studying writing at the University of Washington and a visiting writer had put it on a syllabus my friend shared with me, so I decided to undertake his syllabus as a kind of independent study and read this biography paired with Madame Bovary. It’s perfect for developing novelists (rather than scholars) because it doesn’t cover Flaubert’s whole life, but instead creates a narrative for the question: “How the hell did Flaubert, this mama’s boy so weak with seizures that he had to go live in the country, manage to write a masterpiece that still has the power to pull you into its inner scandals?” At the time I was finishing my MFA thesis—100 pages of a novel that would grow after graduation to 400 pages, and which I would revise for six years, and which I would ultimately never publish. This biography helped me stick with that novel, and later it helped me let it go. This biography made real for me how much goes into a novel that deserves shelf-life. I mean, first Flaubert had to find some way out of the life of a respectable lawyer which his parents had planned for him—in that way, his seizures were a gift. Then, he had to enlist two friends who for some crazy reason decided their buddy Gustave could become a literary genius, and get these friends to come out to his country house for long weekends to read and edit all his pages. And then he had to write this long novel (the first version of The Temptation of St. Anthony) that he was convinced would be his masterpiece, and he had to read it aloud to his friends [and] his mother in this marathon overnight session—and they told him to throw it in the fire! Only after all that could he write Madame Bovary, which was its own journey.

The other thing I love about this book is that Steegmuller writes it in such a novelistic way that you begin to identify with Flaubert. I think bouts of that kind of chutzpah are essential when you’re developing, and maybe you don’t even know how you’re going to pay your rent (I didn’t), and the pages aren’t what you want them to be yet. I’m not proud of this, but I’d have nights of strutting around thinking, I can be a Flaubert, damn it!

JC: Steegmuller gives us Flaubert first, then his masterpiece. But only after giving up on his first manuscript. How common is it for first-time authors to give up on one or more of their first attempts?

RH: I really should take an informal poll to find out, because my hunch is the results would be reassuring! Or at least, reassuring to someone who’s written the first novel, not been able to publish it, and would rather die than not write, so needs to find the bravery to carry on. I suppose knowing a lot of first novels never see publication wouldn’t be so reassuring to writers just starting out. I do know that my mentor at the Warren Wilson MFA program, Frederick Reiken, spent years on a first novel in the proverbial drawer, then went on to write (so far) three brilliant ones, my favorite of which is Day for Night. Rick has shared the wisdom he gained from writing that failed first novel in a craft essay titled “The Author-Narrator-Character Merge: Why Many First-Time Novelists End up with Flat, Uninteresting Characters.” It’s in the anthology of craft essays A Kite in the Wind. I can’t recommend it enough.

Jean Rhys: Life and Work by Carole Angier

I read Jean Rhys’ Voyage in the Dark at 20 years old in an undergraduate class. Everyone else in the class hated this novel, but it struck me like no novel before or since. It’s a painful book but a thing of beauty. I still read it once a year. But I’d never read a biography of Jean Rhys until I spotted Carole Angier’s study, which moves between chapters of pure biography and chapters of purely analyzing each book Rhys wrote, breaking them down into synopsis, themes, and techniques. The thing this biography impressed upon me was that, technique aside (and Rhys’ technique is spectacular), sometimes the writing process can’t be separated from facing your own darkness and working for self-understanding. Jean Rhys was a horrifyingly narcissistic person who hurled abuse at everyone in her orbit. Her novels draw closely from her life and her early novels are, Angier argues and I agree, marred by self-pity. Voyage in the Dark is her most moving novel, I’d say, because it gives the reader a version of Rhys at 20, still innocent and deeply vulnerable. After that novel and Good Morning, Midnight, she didn’t write for almost three decades. Part of her journey back was spending years on this excruciatingly self-lacerating journal in which she imagined herself being tried by a judge for her selfishness. If you ever pick up Angier’s biography, go right to page 463 and you will see the heart of this self-trial, and where it lands her: “I must write. If I stop writing my life will be an abject failure. It is already that to other people. But it will be an abject failure to myself. I will not have earned death.” That’s how she got herself to finally write her best-known novel (though not my favorite!), Wide Sargasso Sea. So much of the work of a novel takes place on pages outside of the novel itself. Only in good biographies do we get to see this.

JC: Angier notes that Rhys had a gift for “distilling truth out of evasion and art out of pain.” What do you think made it possible for her to persist?

RH: Oh, man. Well, unfortunately, a lot of alcohol—way too much alcohol—is part of the equation here. Also, some dedicated enablers. Her second husband worked in the publishing industry, thought that Rhys was a genius, and became her literary agent. Talk about selfless service to art. Some people think that Rhys drove him to death—he had a heart attack shortly after an especially nasty fight with her. So, all of that. And just a deep calling. Literature was ultimate meaning to her.

The Last Love Song: A Biography of Joan Didion by Tracy Daugherty

This biography came out just a few years ago. It’s by a novelist, and it hooked me with its preface, which analyzes on a brilliantly granular language level why Didion (whether you love her or hate her) hooks us. The book is worth its price for that preface alone. I’ll admit, though, that I felt I needed a good shower after a lot of the more tabloid-esque material of the book (Didion’s drinking providing plenty of fodder). Reading this less voyeuristically, I think it’s a valuable biography for writers who come from journalism backgrounds but aspire to create literary work. I come from daily journalism beginnings and I’m prone to denying that journalistic work had any usefulness in writing memoir and fiction. The Last Love Song showed me how Didion’s early years at Vogue did help her develop on the sentence level: “We were connoisseurs of synonyms. We were collectors of verbs.” It was also fascinating to see how she forged a way of being both literary and popularly read by using magazines like Life, knowing their readerships and their formulas and pushing the edges of those strictures. So practical: she needed to get paid! But she did so while deliberately challenging the conventions. So shrewd.

JC: I gather Didion did not cooperate with Daugherty, although many people in her life were willing to do so. How complicated does that make a biographer’s work?

RH: Yes, I can see why she didn’t cooperate with him. He didn’t spare the gritty details, and the portrait of her drinking and her marriage is—how to put this—my heart went out to her, and even as a distant reader I found myself not wanting to know that much. Actually, about how that complicates a biographer’s work (which I don’t know personally, since I haven’t written a biography), this brings us back to John Leggett, author of Ross and Tom. I also love his biography of William Saroyan, and I interviewed Jack, as he was known, at his San Francisco house about it when it was published. He’d started the Saroyan biography as a commission from the Saroyan estate, but then they didn’t like that he’d failed to produce a hagiography. So Jack went forward with an unauthorized Saroyan biography. And the immense challenge there was that the Saroyan estate, he said, then denied all rights to quote Saroyan’s work.

Chekhov: A Spirit Set Free by V. S. Pritchett

I didn’t understand why the writers I loved read Chekhov with such near-religious devotion until I was in my thirties. Until then I felt suspicious, like caring about Chekhov was just some kind of in-club, a membership card to flash. I’m reading the Pritchett biography now in large part to catch up. Like the Steegmuller Flaubert biography, it’s done with a novelist’s touch.

JC: Pritchett teases out the autobiographical elements of Chekhov’s work in a masterful way. What strikes you most about Chekhov’s life?

RH: As far as the biographical bits that draw me to Chekhov now, I’m struck by how he took the pain of abuse he and his siblings suffered from their father, and used it not as a point of grievance, but as a motivation towards compassion. And that, at such a young age, he took on responsibility for supporting his whole family financially, again without bitterness. It goes to show you can be a wholly committed writer and be selfless. Not that I’ve personally figured out how.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·