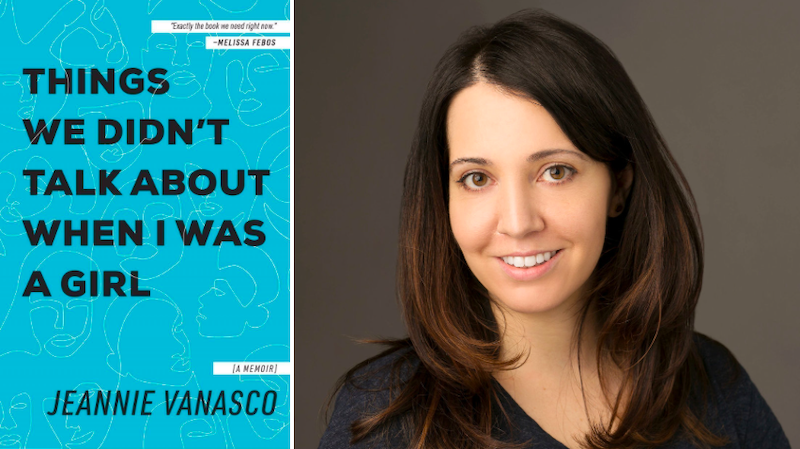

Jeannie Vanasco’s Things We Didn’t Talk about When I Was a Girl is published this month. She shares five books with metanarratives.

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose

In this essay collection, she sometimes reflects on how the writing sustains her. The lyricism itself almost functions as metanarrative, reminding the reader that the essays have been labored over—yet the sentences never strain. The writing works so well it seems inevitable.

Jane Ciabattari: Her opening essay, “The Heart Museum,” is remarkable for so many reasons. Its rhythms, as in the pages in which she begins each paragraph describing the steadiness of the heart with “Even when” (“Even when we’re pressing snooze and rolling over in bed, folding ourselves into our covers and postponing the day’s bubbling over,” “Even when a thought springs fresh in my mind on the subway and solves an essay I’d just about abandoned.”) And wide-ranging passages like this: ”First love is all sensation and ambient zooms, and letting the world ebb. Like writing, occasionally, it feels combustive. Greedy. It’s unsophisticated and coaxes you into making promises about the far future and imbibing the moment. Into growing gullible fast, frantically so, and forgetting about yourself—about your exception. Writing does the same. It lays siege.” And the heartbeats throughout. Do you have favorite moments?

Jeannie Vanasco: I have so many favorite moments! It’s as if each sentence has never existed in the English language before. Take her descriptions of writing: “I’ve heard rumors that writing can feel glamorous. But only glamorous, I’d guess, in the way a stretch limo might feel glamorous. No matter the pomp, one still has to crouch inside.” And: “Writing will never be as satisfying as observing someone whom I knew was terrible get caught in an embarrassing lie; as satisfying as the pop! I anticipate when twisting open a Martinelli’s apple juice or when I pour hot coffee over ice come summer or lace up skates in the winter—the firm tug of hooking the top part of the boot.” And: “And yet, despite claims, no writer hopes for ideas to take complete shape. Approximation is the mark. Many times, writing that clinches lacks incandescence—the embers have cooled. A need for completeness can, off and on, squander cadence. Isn’t it fun to read a sentence that races ahead of itself? That has the effect of stopping short—of dirt and cutaway rocks tumbling down the edge of a cliff, alerting you to the drop.”

How to Disappear Completely by Kelsey Osgood

She opens her memoir about anorexia with a reflection on how other memoirs about anorexia romanticize the illness. Her memoir includes no details that could push the book into an anorexia how-to manual.

JC: Did you have a similar mission in writing your own book?

JV: Definitely. My memoir is not a manual or a manifesto but rather a record of my thoughts and feelings about my conversations with Mark—and how those conversations affect my thoughts and feelings about the rape. Some readers have asked why I don’t hand over the audio recordings to police–the recordings where Mark admits to rape—but in this instance I’m more interested in moral accountability than in legal accountability. I’m not arguing for or against restorative justice. In the book, I’m arguing with myself and thinking through the nuances of a former friendship.

Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot

She uses an epistolary form at times, acknowledging the writing as a letter to the man she loves. “This letter can spiral out of control like me, and maybe you won’t read it, because I might fail to send it, or you might decide your life without me is worth maintaining.”

JC: In a similar way, your texts with Mark throughout your memoir create a contemporary sense of that epistolary form. What do you intend them to bring to the reader?

JV: The transcripts are an example of me giving up some power while also taking it back. Given how rarely women are believed, and given my diagnosis of bipolar disorder, I unfortunately felt I needed him on record admitting to the rape. And he did admit. He said, “It was one of those things where I knew while I was doing it that I shouldn’t be doing it, and I just did it anyway.” So this was my way of putting the focus on his actions. I didn’t want any readers stuck thinking about what they would have done differently to prevent or stop the assault. The transcripts are also my way of bringing the reader in as a character. The reader is invited to join my friends in analyzing the interview transcripts.

Book of Mutter by Kate Zambreno

She reflects on her motivation to write the book—to be released from her grief for her mom—and she describes her attempts over the years to finish it. One of my favorite moments is when she writes, “I am going to erase this. This doesn’t belong here.”

JC: In a blog post for the University of Arizona Poetry Center, Zambreno describes the primary materials and artists she engages throughout this book: “…the fragmented writings and Cells of Louise Bourgeois, Henry Darger’s obsessions, diaries, and weather reports, Roland Barthes’s work on photography coupled with Mourning Diary, his diary of scraps he kept in the days after his mother’s death, concepts of Victorian memorial photography and collection. Then there are the other obsessions that have informed the topography of the text in the 13 years of its conception, threaded throughout, as ghosts and echoes (like an ongoing fascination with Barbara Loden’s 1971 film Wanda, or Helene Weigel’s silent scream in her playing of Brecht’s Mother Courage, or interrogations into various repressive American histories). But there are also the texts that are sometimes seeded as references throughout Book of Mutter, that crucially inspired or gave me permission for its forms (beyond my séance with Barthes, Bourgeois, and Darger.)” Here she includes Peter Handke, Nathalie Sarraute and Claudia Rankine. Did she influence the shape of your memoir? What were the conversations, “ghosts and echoes” that popped up during the course of your writing? (And how long was that?)

JV: I read Book of Mutter after I finished writing Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl. But Zambreno’s approach to writing—the self-aware examination of process—is something she also foregrounds in her early work, Heroines. I like when writers strip away the artifice, acknowledging the writing of their books within their books. She writes about her creative process by way of collage, and that’s a technique I find helpful. I write about this in The Glass Eye, but during the draft stage I use binders to organize my manuscripts. I print everything single-sided and then cut apart paragraphs and sentences, glue them to new pages, shuffle stuff around, write new passages in the margins. It’s all very tactile. The problem enters when my cat Flannery enters the room. She has eaten so many of my sentences.

Dreaming of Ramadi in Detroit by Aisha Sabatini Sloan

In this essay collection, Sloan sometimes reflects on her writing—especially about Detroit “because there is an implicit understanding among people who love Detroit that you shouldn’t talk shit.” She also foregrounds her technique: “Given that the running metaphor in this essay is opera, I’ll self-select: this is a lament.”

JC: I’m fascinated by her layering, and her confidence. Her essay “D is for Dance…” splices a ride around Detroit in her cousin’s squad car (she’s a lieutenant in the Ninth Precinct) with references to her father’s Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera. What makes that approach work so well? Her acute sense of detail? Word choice? The high-low and global cultural span we’re finding available to us today?

JV: Sloan’s declarative sentences lend her writing a confident tone. Yet she also tempers that confidence with an explorative structure. She’s not arguing a point. Her formal experimentation is a means of exploring nuance. She’s a brilliant writer. To quote Durga Chew-Bose again: “Many times, writing that clinches lacks incandescence—the embers have cooled.”

*

· Previous entries in this series ·