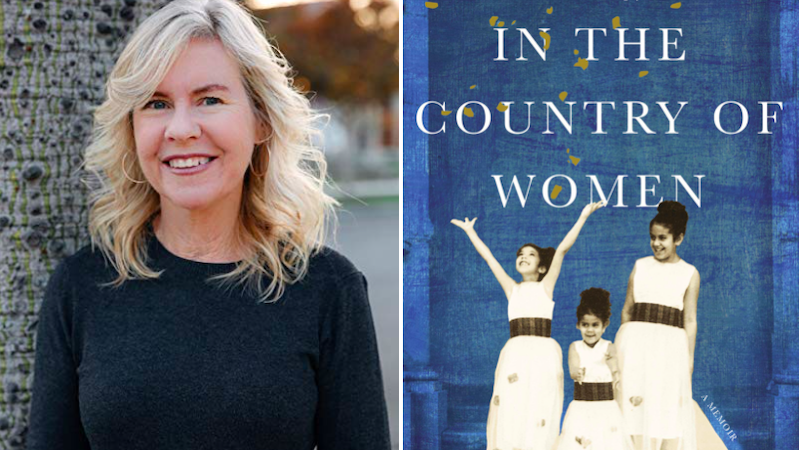

Susan Straight’s In the Country of Women is published this month. She shares five of her favorite memoirs about mixed-race families.

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah

A great inspiration was Born a Crime, which I read three times, which every member of my family read, including my ex-husband from Riverside, and new son-in-law from Ibadan, Nigeria. Noah’s book begins with his mother throwing him from a minibus, and mine begins with my mother accidentally running me over with a 1966 Ford Country Squire. His mother is Xhosa, his father Swiss German. My daughters are black, Swiss-German, French, and indigenous. But mostly, his memoir is a testament to the strength and resilience and humor of his mother, and mine is a testament to all the women who came before me.

Jane Ciabattari: Such intriguing parallels. Which passages or section most dramatized his mother’s strength, resilience and humor?

Susan Straight: So many! His mother is present throughout the book. She is the center of his life, from the unforgettable opening chapter, when she takes Trevor and his baby brother Andrew to three different churches on a Sunday, as is usual, and her car breaks down, causing said minibus to stop for the family. She is the center of his life by the end, when the mechanic she has married, because of that broken down VW, shoots her point blank. In the final pages, she manages to laugh with Trevor in the hospital. Cars, man. Mothers. Trevor Noah ties it all together with his own inimitable voice.

Bad Indians by Deborah Miranda

Just as important was Bad Indians, which I have also read three times, and am teaching now. Miranda’s father was Esselen/Chumash indigenous, descended from the first people of California, who were later forced to live and work at the famous missions. Her mother was French/English/Jewish, raised in Beverly Hills. Their tumultuous relationship formed Miranda’s childhood. As a poet and writer, Miranda recounts indigenous California history and her own like no one I’ve ever read. A pivotal moment in my memoir is when I take my three girls to visit several missions, and my middle daughter says, at nine, “I wouldn’t be buried in the cemetery, because I have Indian blood.”

JC: So much of Native American history taught in the schools is limited to a few details, despite the rich ongoing cultures of the California tribes. Where did your middle daughter learn about California history—in school? In stories?

SS: All California fourth-graders were required, for decades, to build a replica of a California Mission. I had written a chapter about my stepfather, from Canada, helping me build mine when I was nine, and how he helped my oldest daughter build hers. But my three girls and I knew the true history of the indigenous people hadn’t been told to us—and Miranda’s memoir is centered around that vivid, violent past, as told by her own ancestors and other indigenous women. She’s brilliant.

On Gold Mountain by Lisa See

I loved On Gold Mountain as a generational saga filled with the histories of her ancestors on her father’s side, who left China for California, and how See learned so much from them while roaming their amazing antique and artifact-filled stores. Also filled with strong women forebears.

JC: How is it that details about antiques and artifacts act as portals to the past?

SS: Lisa See is such a consummate listener, someone who absorbs history and details when people talk—I’ve seen her do it! As a child, she was fascinated with the antiques, but she heard these remarkable stories from family members, and the reader can imagine being in the store and the voices weaving through the valuables. I could imagine the women murmuring, the smells of herbs and perfume, and feel the ingenuity of her female ancestors in that store. See tied together a hundred years of her own family.

Nobody’s Son by Luís Alberto Urrea

Nobody’s Son recounts Urea’s childhood as descended from a Mexican father and a white Staten Island-born mother, meant he navigated the borders between Mexico and California, the actual space, but also the mental spaces of his tumultuous life. Nobody writes about San Diego and Tijuana like he does. And he’s hilarious. We are the same age, and think so much alike about everything from food to wandering dangerous streets.

JC: Can you offer some specific scenes about food, and about wandering dangerous streets?

SS: His prose is astonishing, filled with the dark tenderness of sitting with his father on the back of a bakery truck, to the violence of his neighborhood, filled with young men who fought. His mother’s rejection of his Mexican identity is painful, but Urrea’s imagination and imagery are singular, as if he made his own beauty in his writing.

Cane River by Lalita Tademy

Cane River was a great read as well, a fictionalized memoir based on six generations of Tademy’s family in Louisiana. I loved the way the women, from enslavement to present day, spent their lives trying to make things better for the next generation, culminating in Tademy’s success in California. Having three daughters who are of mixed-race, thinking about how women who look like them are perceived in society even now, I read this memoir again while working on mine.

JC: Yes, there are clear connections between Tademy’s portrait of six generations of a Louisiana family and your depiction of your husband’s female ancestors, including your mother-in-law, Alberta, who, it seems, taught you so much, and who stands behind your daughters, as well. How did you come up with the structure of your memoir?

SS: The structure was the hardest part. With so many women, all vitally important to the book, chronological order wouldn’t work at all. I wrote chapters about each woman—Alberta’s mother, Daisy, who fled a husband with a gun; my own grandmother, who married my grandfather after he flashed his gun at all the other men in a country dance; my father-in-law’s grandmother, who carried a bullet in her apron pocket when she was nine years old. I realized the talisman of the memoir might be the bullet, and the way the women moved about the country to save themselves and their children, who became Californians.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·