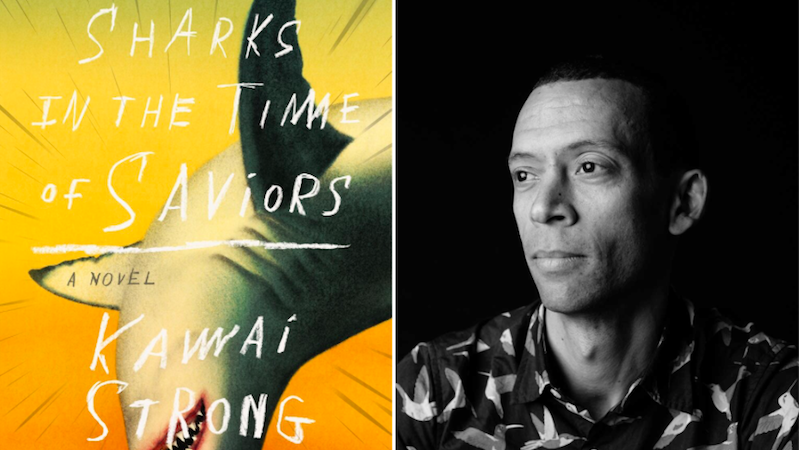

Kawai Strong Washburn’s Sharks in the Times of Saviors is published this month. He shares five great books on Hawai’i.

This is Paradise by Kristiana Kahakauwila

Kahakauwila shows us contemporary Hawai’i from a variety of angles, ranging from a cluster of urban, mixed-race women navigating Honolulu after dark to locals fighting roosters in upcountry Maui.

Jane Ciabattari: On their way to a surfing spot, the women of the housekeeping staff at a Waikiki hotel notice a tourist in a white bikini with red polka dots. They see her again later that night at the Lava Lounge, and one woman warns her: “Hey, Sista, not my place, but. Da guy you wit’ has prison tatts.” She ignores the warning, they hear her say, “This is it. This is paradise.” And in the morning she is proven horribly wrong. How would you explain the ways in which Kahakauwila builds suspense in this story?

Kawai Strong Washburn: There are key sentences of foreboding early on, from the moment the women first see the tourist. Their collective voice continues to silently warn her at regular intervals as the story moves forward, culminating in actual warnings like the one you cite above. But there’s also the rising tension between the local population (expressed through each set of local characters in the story) and tourists as a whole, so there are dual threads of conflicts at play.

Wild Meat and the Bully Burgers by Lois-Ann Yamanaka

The first book of Hawai’i in which I recognized the islands as I’d experienced them, as opposed to how I was told they were supposed to be.

JC: Which books had you read that told you how the islands were “supposed to be?” What does Yamanaka do to bring authenticity to her work?

KSW: It’s less a specific book describing what Hawai’i is supposed to be and more a tidal wave of popular culture: movies, music, postcards, travel magazines, vacation packages, commercials, sporting events, television shows. All presenting Hawai’i as an exotic, packaged experience, offered up to visitors in an unequal exchange. Yamanaka’s work is deeply authentic (and provides relief from said tidal wave) because of its locally-oriented specificity: from the description of places and people to her use of pidgin (Hawaiian patois), to the references and perspectives of her characters. She sets her work in locations that are off the tourist map, and in many cases there’s very little (if any) interaction with the sorts of characters that most Americans are used to reading about (or would recognize themselves in). Instead of those sorts of characters and places, readers local to Hawai’i are given ourselves and our places.

Detours: A decolonial guide to Hawai’i, Ed. by Hokulani Aikau and Vernadette Vicuña Cruz

Roughly formatted to resemble a tourist guide, this volume is comprised of writing, visual art, and transcribed oral histories of contemporary life in Hawai’i, all expressing resistance to the colonial narratives that dominate most foreigners’ ideas of Hawai’i.

JC: The chapter titles alone suggest how enlightening this collection is: “A Downtown Honolulu and Capital District Decolonial Tour,” “What’s under the Pavement in my Neighborhood, Puowaina,” “(Locals Will) Remove All Valuables from You Vehicle: The Kepaniwai Heritage Gardens and the Damming of the Waters,” “Reconnecting with Ancestroial Islands: A Guide to Papahanaumokuakea (the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands).” Do you have a preference for any particular section? Which relates to your own island home?

KSW: It would probably be ‘Part II: Hana Lima/Decolonial Projects and Representations’, which has a heady mix of commentary on current events (such as the protection of Mauna a Wākea, commonly known as Mauna Kea, which has set off legal battles and civil disobedience events) along with descriptions of Native reclamation and restoration projects. I suppose it’s important to mention that I don’t agree with everything that’s said in the book, and yet I respect and value the opinions that differ from my own, and very much love what the book represents as a whole.

Shark Dialogues by Kiana Davenport

Does for Hawai’i what Marquez did for South America.

JC: I’m wondering how Davenport’s first novel, with its multiple generations, Pono the matriarch and the others raised in traditional ways to live in Captain Cook’s Hawai’i, might have influenced yours. Sharks, ancestral spirits, are important to both.

KSW: Sharks and the ʻaumākua (taken both separately and together) are important concepts in Hawaiian mythology, and our novels both reflect that. I hope perhaps people might start to have a different idea of the grace and majesty of sharks, as opposed to the fearmongering and scapegoating that is the current norm. The strongest influence of Davenport’s novel on my own writing is probably her use of magical realism. For a long time I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to integrate elements of mythology and deification of the natural world—important parts of Hawaiian culture—in a way that wasn’t ultimately reductive, or reinforcing stereotypes of indigenous people as “magical” or “uniquely, mystically connected to the land.” But Davenport showed me it was possible.

Ruling Chiefs of Hawai’i by Samuel M. Kamakau

A Native Hawaiian historian follows the chiefdoms of Hawai’i from the time of chief ‘Umi to Kamehameha III; at times it reads less like a history textbook and more like a scholarly Blood Meridian.

JC: What a resource! Kamakau’s mid-nineteenth century sources for his storytelling genealogy, which tracks Hawaiian culture back some eight generations before King Kamehameha I to Umi, were priceless. Did you draw upon his work while writing Sharks in the Times of Saviors?

KSW: I didn’t, actually, although I have been using it heavily (along with many other references) in my current novel, which is still in its infancy. Kamakau’s work is such a rich, fascinating resource, and will greatly expand anyone’s understanding of the history of the islands. It makes Game of Thrones look like a joke.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·