Lars Iyer’s Nietzsche and the Burbs is published this month. He shares five books about visionary youth.

Ferdydurke by Witold Gombrowicz

(Yale University Press, 2012, originally published, Poland, 1937)

Witold Gombrowicz’s mapcap novel Ferdydurke is a celebration of immaturity, mocking convention, propriety, officialdom and high culture. However, this is no straightforward hymn to youth—the protagonist, magically turned from a thirty-year-old writer into a teenage schoolboy—suffers all kinds of humiliations. Still, it’s clear where Gombrowicz’s sympathies lie. Ferdydurke depicts the anarchy of youth—its wildness, its impatience—but it also exposes the anarchism at the base of our schools, our families, and of middle-class life. All authority, Gombrowicz’s novel declares, is usurped. Chaos reigns.

Jane Ciabattari: Why was Ferdydurke banned in Poland for many years after its publication in 1937? What’s so dangerous about its depiction of youth’s anarchy?

Lars Iyer: In a word, ludism. Youth’s queer anarchy, in the rolling riot of Ferdydurke, is the opposite of self-solemnity, of the ponderous weight of adulthood, of the staidness of the old order, of the old monosexualities, just as it laughs at the new order, too: at the new avatars of the Modern, of the Young Girl (a figure later borrowed by the Tiqqun collective) and her right-thinking family. The spirit of youth, of humor, serves no ideological certitude, thumbing its nose at the Nazi-occupiers of Poland and the communists who succeeded them.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

(originally circa 1599-1602)

Hamlet is perhaps not technically a teen (we never learn his exact age—only that he is a student), but I think it’s inevitable that we read him as such—as a doomed adolescent, caught in the Limbo before adulthood in which he lacks a role in the world, a capacity to act. The older generation are either corrupt—his mother has married his father’s murderer, arousing his disgust of the body, of sexuality—or suffocatingly conventional; whence his particular contempt for the all-too-sensible blandishments of Polonius, the advocate of normalcy. The larkishness of his university friends can offer no cheer, and he cannot reciprocate Ophelia’s love. Hamlet’s melancholy leads in one direction. His prevarication, his mixture of juvenile caprice and adult seriousness, finds its fitting resolution in the nihilistic tableau of the final act, with dead bodies littering the stage.

JC: What might be the signature lines from Hamlet that most resemble the nihilistic themes in your new novel?

LI: The first soliloquy has so much:

O, that this too too solid flesh would melt Thaw and resolve itself into a dew! Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d His canon ‘gainst self-slaughter! O God! God! How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable, Seem to me all the uses of this world! Fie on’t! ah fie! ’tis an unweeded garden, That grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature Possess it merely.

Life as “rank,” “gross,” as an “unweeded” garden that has run wild, full of disgusting things. Better not to exist at all than to be part of chaos and corruption. My central cast of characters, never as depressed as Hamlet, although they might to think of themselves as so, run up against the old problem of the meaning of suffering. They’re tempted simply to lay down their arms, to give in. But they’re too alive for that, asking instead how they might impose meaning and order on a dead world—to cultivate their figurative garden in the middle of the suburbs. Nietzsche, their new schoolmate, advises them to drop their pity and self-pity, prizing suffering for the chance of genius that might spring from it. They, in turn, become convinced of Nietzsche’s genius, persuading him to become the frontman for their band…

The Sea of Fertility by Yukio Mishima

(Penguin, 1985, originally published, Japan 1965-1970)

Yukio Mishima is the laureate of fanatical youth. The Sea of Fertility, a novel tetralogy, is about a transmigrated soul, reincarnated at four moments in southeast Asia in the twentieth century. The second novel of the tetralogy, Runaway Horses, set in the early 1930s, depicts a samurai-inspired group of young ultra-nationalists who aim to attack members of the country’s financial elite. The group falls apart. Yet Isao, the reincarnated soul, acts alone, assassinating his target, and then, satisfied that he’s fulfilled the central purpose of his life, commits seppuku, ritual disembowelment, before the rising sun. Has anyone but Mishima conveyed the desire for death, for cleansing self-sacrifice, visible in young men?

JC: Mishima certainly captured a sense of nihilism in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy. And he proved his own commitment by his suicide shortly thereafter; his ritual seppuku mirrored that of Isao and overshadowed his final work. Why do you think the novelist and the man converged in this way?

LI: Mishima’s own terrorist action took place on the same day he completed his tetralogy, storming the Tokyo headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japan Self-Defence Forces, with his private army of adolescents, and taking his life in the samurai style. He sought to turn himself thereby in a glorious object, hoping to inspire the coup that would restore the power of the Emperor. The obvious futility of the action did not concern him, indeed, it made it only shine the more brightly.

Curious, then, that the fourth volume of The Sea of Fertility, set in the Japan of the 1970s, presents a far more farcical suicide. Torū, the protagonist of The Decay of the Angel, is psychologically poisoned by his guardian’s cynicism and disgust. His botched suicide leaves him blind and bitter, living on beyond the age in life at which his previous incarnations died. Did he miss his appointment with destiny—or was there no such thing as destiny in the first place?

Completing the truncated, malformed, blackly cynical The Decay of the Angel on the day of his seppuku, Mishima provides an ironic commentary upon his own action.

Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young Girl by Tiqqun

(Semiotext(e), 2012, originally published France, 1999)

Tiqqun’s provocative work of “trash theory” presents us with The Young Girl—a figure of both the ultimate consumer and the ultimate worker of contemporary capitalism. She’s frivolous about the important issues—the climate crisis, total financialization and commodification—but serious about frivolous ones: the advancement of her career, getting ahead on social media—OMGing and LOLing, tweeting and posting and linking and liking. Why is this figure female? Because of the widely remarked upon feminization of labor in the workplace, and, increasingly, outside of it, which have seen a new emphasis on social skills and emotional work. The Young Girl does not refer to women per se, but to the prematurely cynical shock troops of our financialized hellworld, which, what with looming climatic and financial catastrophe, might not last very long.

JC: You’re drawing a direct line to Tiqqun’s work in your new novel, creating a character, Nietzsche’s sister, who is a Young Girl. How does she go about recruiting other Young Girls?

LI: Nietzsche’s unnamed sister in my novel is a “futurist,” advising companies how to adapt themselves to current trends. She also founds the FailBetter Recruitment Agency and visits the sixth-form of my novel to spread the word.

A current business trend has firms encouraging the anti-corporatism of its potential Millennial and Generation Z employees. Efforts at “internal marketing” see firms promoting work for charity, with feed-the-homeless days, as well as virtue-signaling green initiatives, to make their workers feel part of a meaningful enterprise. It’s a continuation, in many ways, of the playful workplaces of the Dotcoms, aimed to encourage staff loyalty. Nietzsche’s sister is very much part of a world of entrepreneurial rhetoric that looks increasingly threadbare in the face of the climate crisis and looming financial collapse.

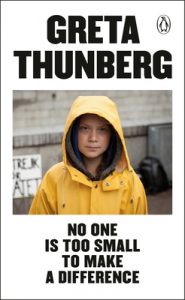

No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference by Greta Thunberg

(Penguin, 2019)

Greta Thunberg is the opposite of the Young Girl, and it’s easy to be cynical about her. Cynicism is our disease—we think we know it all; that we know what human beings are like and presume our future can only be the continuation of our present. Whence the ridicule with which Thunberg is met. It’s because there’s nothing tongue in cheek, nothing witty to be said about her message, that she’s vilified, because the media, and us all are only capable of cynical amusement. And what she presents us with is belief, which is the opposite of cynicism.

JC: Are there any characters in Nietzsche and the Burbs who have belief anywhere close to Greta Thunberg, who has stared down world leaders to deliver her message?

LI: The novel is all about belief—about finding a cause to believe in. For all that they talk about despair, my core characters are too vibrant for Hamlet-style melancholy. They’re surrounded by the inaction of their contemporaries (the “drudges”) and won’t accept inertia as an option. Despite moments of skepticism, and of sporadic Mishima-like faith in wild acts of sabotage, their belief is incarnated in their hopes for their band, which would embody a new ethos, a new way of living in the world. Nietzsche and the Burbs is intended as a celebration of the serious intent of playful youth—of a collective, friendship-filled flight from meaninglessness.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·