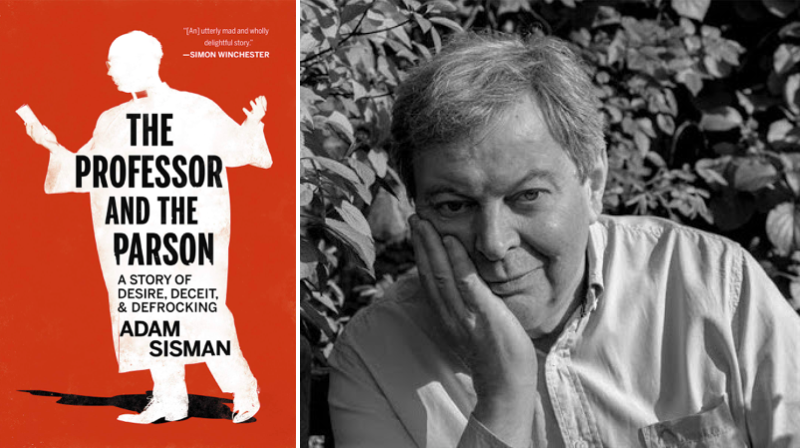

Adam Sisman’s The Professor and the Parson is published this month. He shares five books about con artists.

Hermit of Peking: The Hidden Life of Sir Edmund Backhouse by Hugh Trevor-Roper

The uncovering of an outrageous fraudster, set against the backdrop of Imperial China in its last decadent, intrigue-ridden years.

Jane Ciabattari: What was Backhouse’s biggest trick? Faking the sales of guns to the British, battleships to China? Affairs with Verlaine and the Empress Dowager of China? His “priceless” donations to Oxford’s Bodleian Library?

Adam Sisman: Backhouse made so many preposterous claims that it is hard to rank them. One of my favorites is the account in his boast of enjoying with the then prime minister, Lord Rosebery, “a slow and prolonged copulation which gave equal pleasure to both sides.” At the time of this supposed affair with the noble lord, Backhouse was an undergraduate at Oxford. It seems that the pace was set by the senior party, for, as Backhouse puts it, “my readers will agree that when a young man is privileged to have sexual intercourse with a prime minster, any proposal regarding the modus operandi must emanate from the latter.”

As well as with Verlaine and the Empress Dowager, Backhouse claimed to have had sex with Oscar Wilde; and to have been present with Henry James at a homosexual brothel in London. This last claim has attracted some interest from those who would like to establish James as a gay writer. But there is no more reason to believe this than there is to believe any other one of Backhouse’s ridiculous fantasies.

The Quest for Corvo by A. J. A. Symons

In the extraordinary story of Frederick Rolfe, self-styled “Baron Corvo,” the process of biographical investigation is itself dramatized.

JC: Symons reveals his own process, as he tracks Rolfe through the people who knew him, many of them benefactors he later betrayed. “Though the peculiar inner energy which possessed Fr. Rolfe is beyond analysis,” Symons writes, “the external events of his life, and his reactions to them, can be collated and made comprehensible.” “Charlatan or Genius?” is an apt subtitle. What’s your conclusion?

AS: Symons’s conclusion about Rolfe reminds me of my own about Robert Peters. “I realized too that Peters could only be known from the outside: his inner thoughts and feelings were hidden, and would almost certainly remain so, however much I might discover about him otherwise. Indeed it seemed to me likely that he barely knew himself, because had he done, he surely could not have acted as he did. His motives could only be deduced from his behaviur.” I used the analogy of tracking a particle in a cloud chamber: usually one could not see the man itself, but only the path he left behind.

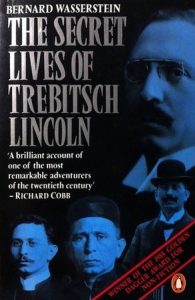

The Secret Lives of Trebitsch Lincoln by Bernard Wasserstein

Revolutionary, spy, missionary, Anglican curate and member of the British parliament, Trebitsch Lincoln was one of the most bizarre figures in modern history. Among this he conned were David Lloyd George, Heinrich Himmler, and J. Edgar Hoover.

JC: A con man in how many countries? His native Hungary, England, Germany, the U.S., China… The research involved in telling this story must have been exhaustive. From your own new book, how hard is it to sift through and tell fact from fiction in the case of such a wide-ranging con man?

AS: In the case of Robert Peters, it was impossible to follow every twist and turn of the tortuous route he followed from country to country and from continent to continent. Sometimes I felt close on his trail; at other times I lost it altogether. In a way it didn’t matter, because the scams he pulled were similar wherever he went; merely adapted to local conditions. He loved America, for example, “because of the opportunities it offered.” America is proverbially a country in which one can reinvent oneself, and begin life anew.

Agent Zigzag: The True Wartime Story of Eddie Chapman, Lover, Betrayer, Hero, Spy by Ben MacIntyre

Eddie Chapman, small-time crook in peacetime, became a double agent in wartime, oscillating between German and British spymasters.

JC: MacIntyre had access to MI5 files to tell his tale of a safecracker turned spy who had no trouble lying under interrogation and seemed to enjoy ever more dramatic action. “Slowly at first, and with great care, Chapman began to build up a stock of secrets that would be of supreme interest to British intelligence,” MacIntyre writes. Evidently Chapman even offered to assassinate Hitler. What happened to him after the war?

AS: After the war Agent Zigzag reverted to type. He returned to the demimonde of London’s West End, where his old cronies welcomed him back. He mixed with gangsters such as Billy Hill, and lived the high life, driving a Rolls-Royce, wearing fur-collared coats, and for a while owned a castle in Ireland and a health farm outside London. In the 1950s he smuggled gold across the Mediterranean. Later he became involved in a complicated plot to smuggle almost a million packets of cigarettes and to kidnap the deposed sultan of Morocco. In the post war years he appeared regularly in court charged with various types of crime, but never again went back to prison. The press loved him, and for a while he even appeared as “honorary crime correspondent” of the Sunday Telegraph, “whose readers he proceeded to warn against the attention of people like him.” Asked if he had any regrets, he answered none. “I like to think that I was an honest villain.”

A Perfect Spy by John le Carré

The author’s father, here unforgettably portrayed, was a “world-class” con man. Philip Roth described this book as ”the best English novel since the war.”

JC: Magnus Pym and his father Rick Pym could be a stand-ins for le Carré (born David Cornwell) and his father, Ronnie Cornwell, who was a notoriously charming crook. In his 2015 memoir The Pigeon Tunnel, le Carré calls his father a “con man, fantasist, occasional jailbird.” And he writes, “From the day I made my first faltering attempts at a novel, he was the one I wanted to get to grips with.” Of all le Carré’s novels, this seems most autobiographical. Why does that seem to make it even better than his other work?

AS: I think that in a way that question answers itself: A Perfect Spy is le Carré’s best book because it is so autobiographical. It comes from a place close to the writer, as surely all the best writing does. David Cornwell is a complex, tormented man, still troubled by the betrayals of his childhood. In writing le Carré’s biography, published in 2015, I came to realize that all his novels are, to a greater of lesser extent, autobiographical; but A Perfect Spy is the best because it comes closest to the truth.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·