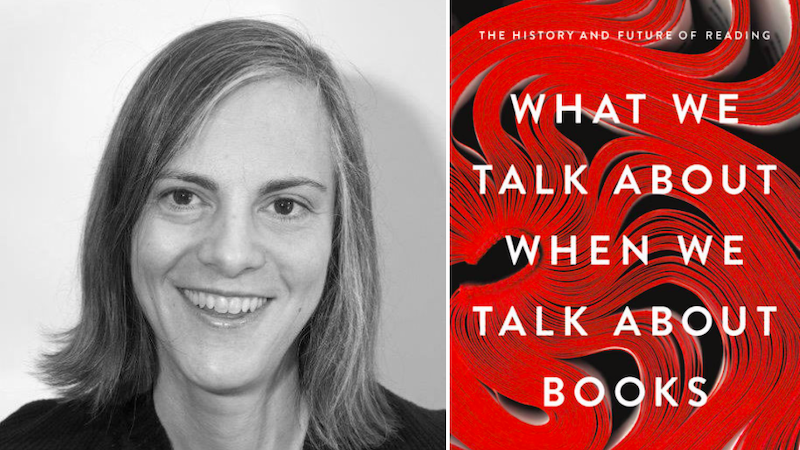

Leah Price’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Books: The History and Future of Reading is published today. She shares five books about books.

The Library Book by Susan Orlean

The Library Book (2018) gives an improbably gripping account of the fire in the Los Angeles Central Library that in 1986 destroyed half a million books, including the complete works of Ray Bradbury. Fish freezers star in Orlean’s account of the soggy books’ fate in the aftermath of the blaze, counterpointing the power of texts with the vulnerability of the objects that embody them.

Jane Ciabattari: As you point out in your chapter “Reading Over Shoulders,” Orlean also reminds us that “libraries stop the clock, returning adults to a different era and a more innocent self.” “I was flooded by a sense of absolute familiarity, a gut level recollection of this journey, ” Orleans writes as takes her first-grade son to meet the librarian at her local library in Los Angeles. Do you have similar experiences of visiting libraries?

Leah Price: Well, when I move to a new city the first place I always go is the library—the familiar call numbers make me feel grounded even before I’ve unpacked my own books at home. But Orlean’s sense of libraries as a place to retreat from the upheavals of history is only half the story. I don’t think she is describing libraries as unchanging or invulnerable. On the contrary, her memories introduce an account of how easily a few seconds of fire can change a collection that took decades to amass and catalog. Likewise, in What We Talk About When We Talk About Books I tried to show how the printed books that feel comfortingly familiar are actually extremely dynamic objects: the first commodity to be sold on credit in the 19th century, the first to be bar-coded in the 20th. This is why I’m uncomfortable with the “technology-free reading rooms” that many libraries are now rolling out. Lovely as it is to turn off the phone and open a paperback, that paperback is a technology too.

The Book by Amaranth Borsuk

Poet, scholar and artist Amaranth Borsuk gives an equally punning title to The Book (also 2018). Like Orlean, she sees books as physical objects available to more senses than sight alone, but her emphasis is on the range of different structures taken by the book, from cuneiform tablets to palm-leaf sutras to competing e-book file formats. Thing, idea, interface, prompt: Borseuk shows that books are much more than just a bucket into which words can be stuffed.

JC: Borsuk describes a book as “a portable data storage and distribution method,” a definition that spans the centuries. I think of how she tracks the evolution of the original tablet, the transition from clay tablets to papyrus, and how so many readers now use “tablets” to read. Do you have a sense of the next step in the evolution of reading?

LP: Part of what I love about Boruk’s account is that its shape is circular, more than linear: old rhythms of reading don’t go away, they just take on new forms. But it seems clear that the next challenge facing reading is how to make time— how to carve out the pockets of dead time that, since the emergence of smooth and well-lit public transportation in the 19th century, printed matter has rushed in to fill. For now, at least, the best contender for those in-between nooks and crannies of time that are hospitable to reading because they’re no good for anything else is the audiobook, and if I had a sixth title it would be Matthew Rubery’s unputdownable history (also available as an audiobook) The Untold Story of the Talking Book.

Reading the Romance by Jan Radway

I’ll balance out Orlean and Borsuk’s recent volumes with an oldie but goodie: Jan Radway’s Reading the Romance launched a revolution when it appeared in 1984, because her feminist argument took its case study from a kind of reading that both literary critics and feminist activists despised. Interviews with their readers showed, surprisingly, that even though the content of these romances was resolutely retrograde, nonetheless the act of carving out me-time for reading could be reclaimed as a feminist act.

JC: How do you think Radway’s argument holds up today?

LP: Ebooks have been a boon for genre fiction, including romance fiction—and women continue to read quite differently from men, beginning with the fact that they read more. In the US that holds especially true for books—magazines and newspapers come closer to being evenly distributed. Although American women’s wages lag behind men’s only somewhat less than they did when Radway was writing, we continue to outspend men on books. Likewise with time: the average American woman has less disposable time than the average man, because we work more of a second shift at home, but we still spend more money on books and more time on reading. So perhaps reading remains valuable as an assertion of the right not to be efficient, not to get through tasks.

Too Much to Know by Ann Blair

In a more erudite vein, Ann Blair’s Too Much to Know (2010) conveys a message that’s either crushing or comforting, depending on your temperament: that digital natives’ sense of being buried under information is nothing new. Blair’s deep research allows her to trace information overload backward to the period between around 1500 and 1700, and to reconstruct solutions that past scholars found to that problem. We might do well to follow suit.

JC: Do you think the invention of the printing press led to an information explosion that parallels today’s digital revolution? What can we learn from how scholars managed information in that period?

LP: One thing that either depresses me or gives me hope, depending on my mood, is that Blair shows how early modern scholars fought fire with fire: the more books they were buried under, the more indexes and finding aids and concordances they compiled.

A History of Reading by Alberto Manguel

A History of Reading (1996) offers an essayistic tour through the varied forms that this apparently simple practice has taken over the centuries—secret or public, silent or communal, prescribed or proscribed. Along with way are some unforgettable vignettes, like workers in Cuban cigar factories paying one of their number to act as a human audiobook to while away the hours.

JC: Manguel also points out that the book’s most popular form allowed it to fit comfortably into the reader’s hand. Even in Greece and Rome, where scrolls were used for all kinds of texts, he points out, for private missives were written on “small, hand-held, reusable wax tablets, protected by raised edges and decorated covers.” Do you think this carries through into our reading habits today?

LP: Yes, books were definitely the original hand-held device for reading—and the difference between a lectern-sized folio and a pocket-sized duodecimo was every bit as consequential as the difference between a desktop computer and a smartwatch. But across eras and technologies, one constant has been the tradeoff between making objects easy to carry and making them easy to use. The book that’s easiest to carry is often the hardest to read away from good lighting, and as Amazon endlessly reminded users in ads for the original Kindle, new and shiny digital devices couldn’t necessarily stand up to the glare of al fresco use.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·