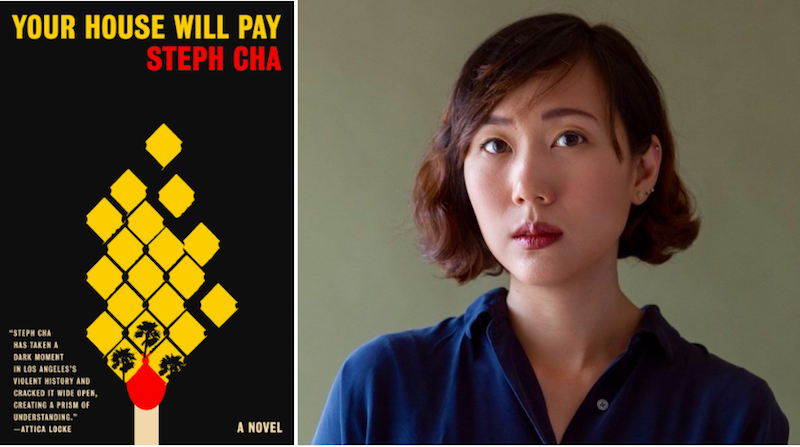

Steph Cha’s Your House Will Pay is publishing today. She shares five American social crime novels.

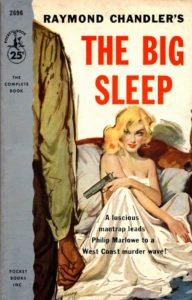

The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler

Chandler certainly had his blind spots, but he knew how to use noir to explore and expose the world around him. Phillip Marlowe took on police corruption, wealth inequality, and war trauma while solving murders and boozing.

Jane Ciabattari: Amazing to think Chandler’s first novel was published in 1939. It still feels current, perhaps because police corruption, wealth inequality and the rest have never gone away. His distinctive language grabs you. When Marlowe visits the house of his wealthy client for the first time, he notices the main hallway of the Sternwood place was two stories high, the entrance doors “would have let in a troop of Indian elephants,” the trees behind the garage are “trimmed as carefully as poodle dogs,” the young woman he encounters is “twenty or so, small and delicately put together, but she looked durable.” How much do you think language and humor set the stage for Chandler’s hardboiled detective?

Steph Cha: When I first read The Big Sleep as a freshman in college, I was as taken with Chandler’s voice and language as I was with his depiction of Los Angeles. Chandler is probably L.A.’s most definitive novelist, and it’s because of that hardboiled tone and atmosphere, without which Marlowe would have been a much more generic character, lost in some convoluted mysteries. Chandler used his sharp observations and devastating wit to skewer the people and institutions of L.A.

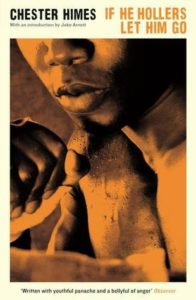

If He Hollers Let Him Go by Chester Himes

Himes wrote a series of hardboiled detective novels, but this one is less a mystery than a book loaded with the horror and threat of racism and violence. It’s a raw, difficult book that shows the ugliness of America in the 1940s.

JC: What’s fascinating about this 1947 Himes novel is how he keeps the noirish atmosphere but substitutes a black man working in a shipyard for the detective; instead of a mystery to be solved, Himes describes the ordinary horrors in his life in Los Angeles during World War II. From his nightmares, which Himes describes so skillfully, to his continual anxiety and building frustration at how badly he is treated by white people in L.A. as he travels around the city— “living every day scared, walled in, locked up”—this is a portrait of a man on the verge. How do you see the historic fact of the Japanese citizens being rounded up and sent to internment camps during this period contributed to his experience of this racism?

SC: Himes lived in a time when America was governed by overt, legal white supremacy. This manifested in the treatment of black people––who were considered good enough to die for the country, but not to live in it as equal citizens before the law––and, of course, the disgrace that was the internment of Japanese Americans. Black Americans and Asian Americans have had very different struggles in this country, but Himes recognized that bad news one for one group was bad news for the other. His protagonist Bob Jones saw the internment as a personal threat, another indication that he was not safe.

Southland by Nina Revoyr

In this Los Angeles masterpiece, Revoyr explores the history of the Crenshaw district in the 20th century by delving into a terrible crime committed during the 1965 Watts Rebellion. This was the book that made Your House Will Pay feel possible.

JC: How did Southland influence your new novel?

SC: Southland helped me see how the story of a crime could unlock the history of a neighborhood, and with it, the history of Los Angeles and––I’m being serious here––America. The novel follows two families––one Japanese, one black––from the 1930s to the 1990s, covering everything from the Japanese American internment to the Northridge earthquake, with a particular focus on the Watts Rebellion. Revoyr inhabits the points of view of both a Japanese-American woman and a black man with great depth and empathy, and she writes compellingly about Los Angeles in chaos. I owe a lot to that book.

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen

The Sympathizer is an intricate, propulsive spy novel that uses crime and intrigue to examine heavy themes like identity, loyalty, immigration, and politics. Nguyen also flays Francis Ford Coppola and other American narrators of the Vietnam War along the way.

JC: The Sympathizer takes the form of a confession by an unnamed North Vietnamese spy. Nguyen has emphasized that it’s a confession written by one Vietnamese man to another Vietnamese, the interrogator—in essence, he’s transforming the English-language novel about Vietnam and the Vietnam War by removing the American perspective that has dominated literature and marginalized the Vietnamese. After the fall of Saigon, his narrator moves to the Los Angeles where, at one point, he works as an authenticity advisor for a Hollywood film called “The Hamlet,” which bears a strong resemblance to “Apocalyse Now.” He detests the film. “I had failed and the Auteur would make The Hamlet as he intended, with my countrymen serving merely as raw material for an epic about white men saving good yellow people from bad yellow people. I pitied the French for their naïveté in believing they had to visit a country in order to exploit it. Hollywood was much more efficient, imagining the countries it wanted to exploit….In this forthcoming Hollywood trompe d’oeil, all the Vietnamese of any side would come out poorly, herded into the roles of the poor, the innocent, the evil, or the corrupt. Our fate was not to be merely mute; we were to be struck dumb.” Nguyen told NPR’s Terry Gross that The Sympathizer was his “revenge against Francis Ford Coppola.” What does his narrator’s attitude toward the film say about his own double nature, expressed in the opening lines: “I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I am also a man of two minds. I am not some misunderstood mutant from a comic book or horror movie, although some have treated me as such. I am simply able to see any issue from both sides.”

SC: It’s funny, as someone who’s never seen Apocalypse Now, I know more about that movie from Nguyen and The Sympathizer than I do from anywhere else. Take that, Coppola! I’ve heard Nguyen talk about the movie, and he acknowledges that it’s a great work of art, while also treating it critically. The Sympathizer‘s narrator is defined by his double nature, his sympathetic point of view, and it makes sense to me that these things would come into focus when discussing American pop culture. I grew up Asian in American society, reading books and watching TV and movies that almost never acknowledged people who looked like me. It was impossible to avoid loving stories where Asian Americans just didn’t exist, or were treated poorly––like Fargo, which happens to be one of my favorite movies. I think this sort of flexibility is a necessary byproduct of growing up in the cultural margins. You have to be able to hold two thoughts at once to participate in the mainstream while maintaining your own identity.

Heaven, My Home by Attica Locke

I’d categorize Locke’s entire body of work as social crime fiction––she knows how to cut deep with the tools of crime fiction, laying bare the systemic dysfunctions that lead to violence. Her newest, Heaven, My Home, reckons directly with white supremacy in the Trump era.

JC: In her Highway 59 series about a black Texas Ranger, who as this novel begins is investigating a double murder involving the “Aryan Brotherhood of Texas,” Locke seems to be filling in the back story on the white supremacist groups that have become more visible since the 2016 election but have always been woven into the landscape of East Texas. Did you encounter surprises in her sections about the region’s social history?

SC: Yes, definitely. I don’t want to give too much away, but I was especially fascinated by the story of Hopetown, a historic freedmen’s community, and the fight for its land. The first book of Locke’s I read was The Cutting Season, a superb mystery that turned on property ownership. So much of American history has been defined by the thwarting of black property rights and home ownership, from enslavement to redlining to gentrification, and that history is nothing if not a series of egregious crimes. I’d actually love to see more crime fiction that delves into this territory.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.