The past is not dead. In fact, it’s not even past.

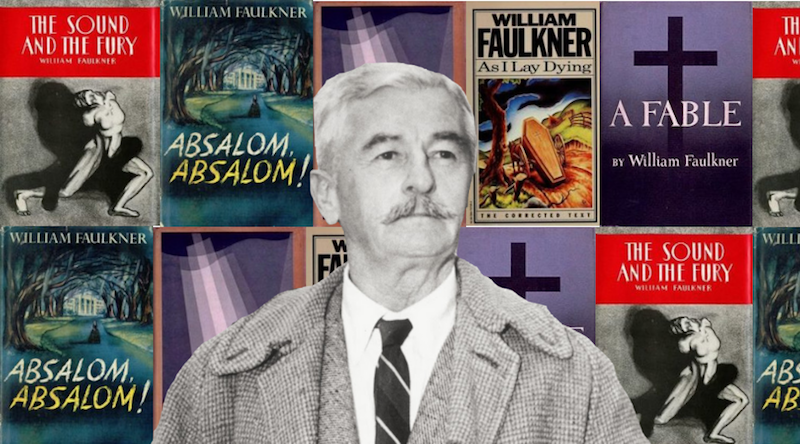

Tomorrow, September 25th, marks the 111th birthday of Mississippi’s marquee modernist and the granddaddy of Southern Gothic literature: William Cuthbert Faulkner. One of the most garlanded authors in the history of American letters (with a Nobel, two Pulitzers, and two National Book Awards to his name), Faulkner’s novels and short stories—largely set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, MS—are legendary for their cerebral, stream of consciousness style and grim, often grotesque, happenings. His fictional characters are spiritually impoverished southerners: weary slaves and their embattled descendants, desperate white sharecroppers, morally decayed aristocrats, bitter families with buried secrets.

Below, we look back on a selection of classic reviews of some of Faulkner’s most famous novels—from his notoriously difficult psychological opus, The Sound and the Fury (1929) and the multi-voiced masterpiece, As I Lay Dying (1930), to the WWI-set late-career Christian allegory, A Fable (1954).

*

The Sound and the Fury (1929)

Clocks slay time…time is dead as long as it is being clicked off by little wheels;

only when the clock stops does time come to life.

“It is customary to label as experimental books that do not conform to traditional modes of writing, but the traditions have been violated so often of late that this designation no longer fits. The Sound and the Fury, by William Faulkner, is the latest novel that defies classification. To many it will be as incoherent as James Joyce, but its writer is a man of mature talent, and the story, if read with patience, turns such a powerful light on reality that it gains a fast grip on the emotions of the reader.

The books tells the story of a rotting southern family from the viewpoint, for the most part, of an idiot whose present and past are hopelessly jumbled. The distortion in his eyes is so great that as a man of 33 years he is still seeing the events of his boyhood as if they were actually taking place once more. The author, endeavoring to record the psychological reaction of Benjy and the other members of this strange household in terms of their own inability to record logically, tries in a style almost as idiotic as the idiot’s thought process. Hence the reader’s difficulty.

…

“But we cannot dismiss the book merely because some passages are difficult. It has the baffling virtue of making the reader want to understand all the devious ways of these creatures’ minds. On the face of it this is a family not worth artistic attention. And yet the dumb suffering of Benjy; the rich, unselfish devotion of his sister, Caddie, who becomes the plaything of circumstance; the harsh brutality of Jason; the sensitive, self-tortured despair of Quentin, the only one of the family who is educated; and the simplicity of Dilsey, the family servant; together with a view of the broken lives of mother and father, beget an emotional sympathy for these poor players which is proof of the author’s talent.”

–Harry Hansen, The Detroit Free Press, November 17, 1929

*

As I Lay Dying (1930)

My mother is a fish.

“This is a family of groundlings tied to the land, subject to the elements, to the seasons, and to natural disasters. Their lives are unmediated by culture, schooling, or money. It is as if the universe pressing down on them is created by themselves.

Faulkner does a number of things in this novel that all together account for its unusual dimensions. Nothing is explained, scenes are not set, background information is not supplied, characters’ CVs are not given. From the first line, the book is in medias res: ‘Jewel and I come up from the field, following the path in single file.’ Who these people are, and the situation they are dealing with, the reader will work out in the lag: the people in the book will always know more than the reader, who is dependent upon just what they choose to reveal. And at moments of crisis and impending disaster, what is happening is described incompletely by different characters, so as to create in the reader a state of knowing and not knowing at the same time—a fracturing of the experience that has the uncanny effect of affirming its reality.

…

“Apart from its technical achievement, and the descriptive prowess here as in all of Faulkner’s major works, As I Lay Dying can be read as having been written in anticipation of the South’s cultural designation as the symbolic face of the Great Depression. Someone who knew the South, as Faulkner did, would not abide that sort of reductionism. There is no claim of social inequity in this novel; there’s barely a moment or two of compassion. Suffering is not seen as a moral endowment, nor is poverty seen as ennobling.

…

“Faulkner wanted to write a tour de force and he did. His famous claim is that he pulled it off in six weeks. His biographer, Joseph Blotner, says it was more like eight. The book would have been astonishing if it had taken eighty. It is a virtuosic piece, displaying everything that Faulkner has at his disposal, beginning with his flawless ear for the Southern vernacular.”

–E.L. Doctorow, The New York Review of Books, May 24, 2012

*

Light in August (1932)

Dear God, let me be damned a little longer, a little while.

“With this new novel, Mr. Faulkner has taken a tremendous stride forward. To say that Light in August is an astonishing performance is not to use the word lightly. That somewhat crude and altogether brutal power which thrust itself through his previous work is in this book disciplined to a greater effectiveness than one would have believed possible in so short a time. There are still moments when Mr. Faulkner seems to write of what is horrible purely from a desire to shock his readers or else because it holds for him a fascination from which he cannot altogether escape. There are still moments when his furious contempt for the human species seems a little callow.

But no reader who has followed his work can fail to be enormously impressed by the transformation which has been worked upon it. Not only does Faulkner emerge from his book a stylist of striking strength and beauty; he permits some of his people, if not his chief protagonist, to act sometimes out of motives which are human in their decency; indeed, he permits the Rev. Gail Hightower to live his life by them. In a word, Faulkner has admitted justice and compassion to his scheme of things. There was a hint of this to come in the treatment of Benbow in Sanctuary. The gifts which he had to begin with are strengthened—the gifts for vivid narrative and the fresh-minted phrase. His eye for the ignoble in human nature is more keen than ever, but his vision is also less restricted.

There are two or three scenes in this book more searing than anything Faulkner has heretofore written, but they are also better integrated. Although the pattern of Light in August is streaked with red, there is a blending here with colors both more subdued and more luminous than were customary to his palette. The locale is again the ‘deep South’; and the characters include the white trash of which he has drawn such relentless portraits, plain folk of a better strain, whites of a higher order, Negroes, and for the subject of his most detailed attention a poor white with a probable mixture of Negro blood.

Light in August is a powerful novel, a book which secures Mr. Faulkner’s place in the very front rank of American writers of fiction. He definitely has removed the objection made against him that he cannot lift his eyes above the dunghill. There are times when Mr. Faulkner is not unaware of the stars. One hesitates to make conjectures as to the inner lives of those who write about the lives of others, but Mr. Faulkner’s work has seemed to be that of a man who has, at some time, been desperately hurt; a man whom life has at some point badly cheated. There are indications that he has regained his balance.”

–J. Donald Adams, The New York Times, October 9, 1932

*

Absalom, Absalom! (1936)

Tell about the South. What’s it like there. What do they do there. Why do they live there. Why do they live at all.

“The new novel by William Faulkner is worth all the effort required to read it. That is not faint praise. In Fact, it is an almost inevitable primary statement. For Mr. Faulkner again is writing—in Aldous Huxley’s phrase—as though the hounds were after him.

The first few pages of Absalom, Absalom! give the impression of being the start of an escape from Devil’s Island. The reader will have that same sense of plunging into a jungle though which no trails run, of the necessity for labored flight though a malevolent, unknown, fever-stricken land. It is a land of tropical overgrowth. Sentences grow to immense lengths and twist and writhe as though consciously blocking movement. Nightmare emotions rise like djinns from insignificant-seeming causes. Phrases spread out, pushing their wiry lengths down half a page.

…

“Yet there was no simpler way in which he could have told it. Substance cannot be blown up with shadow—until men and women stand huge and important, made massive by a mood—by direct, simple declaration. He has told his story as it should be told to satisfy himself, and while it is entirely conceivable that this book may narrow the audience that was made fairly large by Sanctuary, those who complete the reading of this novel will find that it is an even more remarkable achievement, a better novel, than was Light in August, his finest novel before this.”

–Robert Van Gelder, The New York Times, October 26, 1936

*

A Fable (1954)

War is an episode, a crisis, a fever the purpose of which is to rid the body of fever.

So the purpose of a war is to end the war.

“A modern allegory to which each reader will append his own symbolism, his own interpretation. This is slated for a wide acceptance on intellectual snob appeal, but most honest readers will confess to some difficulty in coming to grips with the essential significance. Conceived as World War II approached its last year, the story envisions World War I—in the trenches in France—coming to an end as the soldiers mutiny. The inspiration of the mass movement is a figure symbolic of the Christ. The action parallels the span of Holy Week—with the triumphant entry, the Last Supper, the Crucifixion, the the resurrection. Judas is there, and Peter, the apostles, Pilate and Herod, the Marys, and so on—recognizable, but distorted-although never with irreverence. Creatively, it is an extraordinary achievement with its underlying commentary on an unready world. Practically, it is difficult reading, and often obscure.”

–Kirkus Reviews, August 1, 1954