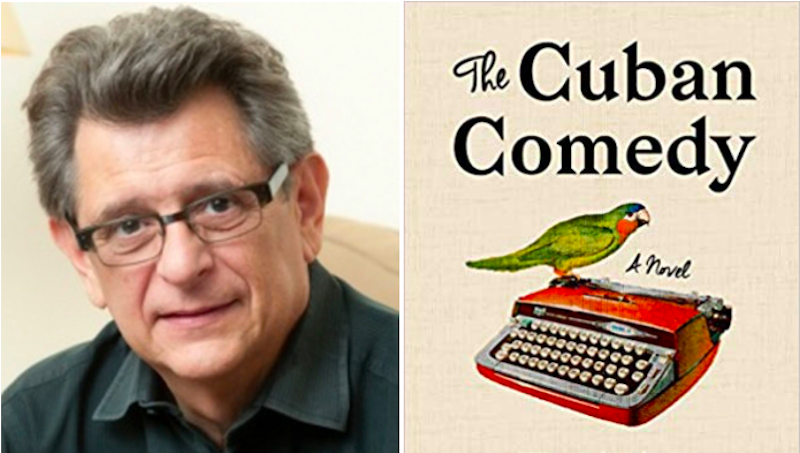

Pablo Medina’s The Cuban Comedy is published this month. He shares five essential Cuban Novels (available in English translation).

The Kingdom of This World by Alejo Carpentier

Though this novel takes place mostly in Haiti during that nation’s struggles for independence in the 18th and early 19th centuries, it remains a classic of Cuban literature by an author who first identified Latin American magic realism as “lo real maravilloso.” It is a must read by anyone wanting to understand the awful legacy of slavery in the Caribbean.

Jane Ciabattari: You translated the most recent edition of The Kingdom of This World, which was first published in 1949. What was your experience in working so closely with the language of Carpentier’s dark and violent tale? Did he have any influence on The Cuban Comedy?

Pablo Medina: Translating The Kingdom of This World was both arduous and beautiful. I spent many years working its densely baroque sentences in a way that made them palatable to contemporary Anglophone readers without losing the essential qualities of Carpentier’s masterly historical voice, a voice that thunders and moans with equal vehemence. I cannot deny that it had a deep influence on The Cuban Comedy and on the novel I am currently writing. My books tend to be responses or accompaniments, if you will, to whatever I am reading while I write.

Paradiso by José Lezama Lima

It took Lezama Lima 20 years to write this book, first published in 1966. It is a symphonic novel by one of Cuba’s great writers and a magnificent example of the Cuban baroque. Young Cubans still read the most salacious parts to one another.

JC: Yes. In his New York Times review, Edmund White called Paradiso “reckless, voluptuous, sly and unrelentingly sexual…. A masterpiece of the modern Spanish Baroque.” Do you have a favorite passage?

PM: Paradiso is a sensual book. Known as a gourmand of insatiable appetites, Lezama could write about food like no one else. Doña Augusta’s banquet in Chapter 7 is memorable, not because of the menu, which includes plantain soup, a seafood soufflé on which rest perfectly cooked langoustines, a golden roast turkey (the word turkey sounds so goofy next to the Spanish word pavón), and a frozen custard dessert with coconut and pineapple, but because of Lezama’s voluptuous description. By the time I finished reading about Augusta’s banquet, my stomach was empty but my mind was stuffed. I have tried in several of my books to reproduce Lezama’s wondrous capacity to evoke the delights of eating, but so far I’ve not quite gotten it right.

Infante’s Inferno by Guillermo Cabrera Infante

Set in pre-revolutionary Havana, Infante’s Inferno is a relentless sexual romp by a narrator who is a sexual predator with few redeeming qualities other than a remarkable capacity for punning. In the end Cabrera Infante offers a mordant (and hilarious) critique of macho predatory attitudes.

JC: This young Don Juan’s introduction to Havana includes a ride on the Route 23 bus with by his father’s best Havana friend, Eloy Santos. The narrative is so earthy and vivid. As is Eloy Santos’s description of being “burnt by the pox”—and how he had died of syphilis and been brought back to life by a blow torch. Are these stories “autobiographical”?

PM: Cabrera Infante once made that claim, but how can one certify the veracity of what’s been written in an autobiographical novel? The label itself brings together two oxymoronic concepts—autobiography and novel. The sexual conquests Cabrera Infante writes about are, in many cases, based on experiences he had as a young man, but many others are, no doubt, the fabrications of a voyeur. Brought back to life by a blow torch? Sure, it happens all the time. What influenced me most about this book, however, were not the sexual adventures of a young pícaro but the beautiful excesses of its language and its love affair with the city of Havana, both traits that abound in all of Cabrera Infante’s works.

The Autobiography of Fidel Castro by Norberto Fuentes

I can only describe this book, published in 2004, as a tour de force written in the voice of Fidel Castro. Fuentes was a member of Castro’s inner circle until he fell out of favor and had to high-tail it out of the island. I couldn’t put it down.

JC: He certainly captures Castro’s voice, sitting aboard his designated VIP plane, Cubana Airlines CU-T1208, writing his memoirs while everyone else sleeps, even referring to The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini as his guide. Is that Fuentes’s sly wink at his braggardly persona?

PM: Yes, of course. The Fidel Fuentes paints (accurately and cynically, I believe) is both a creature of his enormous ego and a man driven to convince others of his own truth, which is the only one considering. When others disagree with him, he does not try to accommodate their views, he silences them any way possible, and that includes exile, jail, or execution. Though García Márquez assured Fidel that the dictator he writes about in The Autumn of the Patriarch was not in the least based on him, the fact remains that that there are distinct similarities between the Fidel of Fuentes’ book and the patriarch of García Márquez’s. In the end, all authoritarian figures wind up resembling one another. They are, after all, all too human, all too steeped in themselves.

Everyone Leaves by Wendy Guerra

Told via a diary that begins in childhood and ends in the narrator’s early twenties, Everyone Leaves (2006) is the story of a woman’s coming of age in Cuba, having to face privation, poverty, and a dysfunctional family. Wendy Guerra tells it straight, often brutally so, and her story makes for a stunning novelistic achievement.

JC: I also treasure Guerra’s 2016 novel Revolution Sunday, which opens with the narrator Cleo (in Achy Obejas’ translation) describing Havana as “this promiscuous, intense, reckless, rambling city where privacy and discretion, silence and secrets, are almost a miracle; a place where light finds you no matter where you hide.” Cleo is under surveillance after her parents are killed in a mysterious car crash. Guerra is of a new generation, coming of age in post-revolution Cuba, with a connection to the past in Gabriel Garcia Marquez. How would you describe the contributions she’s making to the literary lineage you’ve outlined here?

PM: Guerra is not afraid to look the revolution in the eye and the teeth and the throat. She belongs to a generation that experienced firsthand the best and worst the new regime had to offer and has no illusions about the reality it has imposed on the Cuban people—the privations, the lack of individual freedoms, and the failure of its leaders to live up to the reforms they once promised. Free education and health care? Yes, of course, but as a relative of mine explained when I visited Havana, “I’m not always sick and I’m not always reading.” Corruption is rife. If you want to survive in Cuba, you have to resort (assuming you have convertible dollars) to the black market and therefore break the law. Therefore, everyone is a criminal. Her work is not that of active resistance or protest but of disillusion. No hay nada que hacer, as we say in Spanish. Nothing to do but to survive, via any means possible. Nevertheless, at the end of Revolution Sunday, the narrator asserts, “Without Cuba, I don’t exist. I am my island.” This is perhaps why Wendy Guerra insists on not leaving the island permanently, and this is why I love her work as much as I do. I too am nothing without Cuba.

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.